Ottessa Moshfegh in The Paris Review:

This one time, my dad bought me a house in Providence, Rhode Island. It was a two-story fake Colonial with yellow aluminum siding on Hawkins Street. We bought it from the bank for $55,000; it was one of many properties under foreclosure in the city in 2009. Dad and I had spent a few days driving around and looking at these houses. In one driveway, I found a dirty playing card depicting the biggest penis I could ever imagine—I still have it. In one basement, the realtor had to disclose, the former owner had tied his girlfriend’s lover to a chair, tortured him, and then shot him in the head.

This one time, my dad bought me a house in Providence, Rhode Island. It was a two-story fake Colonial with yellow aluminum siding on Hawkins Street. We bought it from the bank for $55,000; it was one of many properties under foreclosure in the city in 2009. Dad and I had spent a few days driving around and looking at these houses. In one driveway, I found a dirty playing card depicting the biggest penis I could ever imagine—I still have it. In one basement, the realtor had to disclose, the former owner had tied his girlfriend’s lover to a chair, tortured him, and then shot him in the head.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

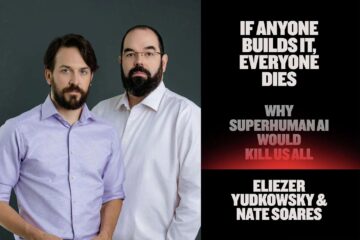

Most people in AI safety (including me) are uncertain and confused and looking for least-bad incremental solutions. We think AI will probably be an exciting and transformative technology, but there’s some chance, 5 or 15 or 30 percent, that it might turn against humanity in a catastrophic way. Or, if it doesn’t, that there will be something less catastrophic but still bad – maybe humanity gradually fading into the background, the same way kings and nobles faded into the background during the modern era. This is scary, but AI is coming whether we like it or not, and probably there are also potential risks from delaying too hard. We’re not sure exactly what to do, but for now we want to build a firm foundation for reacting to any future threat. That means keeping AI companies honest and transparent, helping responsible companies like Anthropic stay in the race, and investing in understanding AI goal structures and the ways that AIs interpret our commands. Then at some point in the future, we’ll be close enough to the actually-scary AI that we can understand the threat model more clearly, get more popular buy-in, and decide what to do next.

Most people in AI safety (including me) are uncertain and confused and looking for least-bad incremental solutions. We think AI will probably be an exciting and transformative technology, but there’s some chance, 5 or 15 or 30 percent, that it might turn against humanity in a catastrophic way. Or, if it doesn’t, that there will be something less catastrophic but still bad – maybe humanity gradually fading into the background, the same way kings and nobles faded into the background during the modern era. This is scary, but AI is coming whether we like it or not, and probably there are also potential risks from delaying too hard. We’re not sure exactly what to do, but for now we want to build a firm foundation for reacting to any future threat. That means keeping AI companies honest and transparent, helping responsible companies like Anthropic stay in the race, and investing in understanding AI goal structures and the ways that AIs interpret our commands. Then at some point in the future, we’ll be close enough to the actually-scary AI that we can understand the threat model more clearly, get more popular buy-in, and decide what to do next. We can’t just have a country where people, being people, get mad and rowdy every once in a while and shout at or beat each other up. No, we have to live a country where people are constantly murdering other people.

We can’t just have a country where people, being people, get mad and rowdy every once in a while and shout at or beat each other up. No, we have to live a country where people are constantly murdering other people. A woman gnaws at her nails: one hand in her mouth, the other clutching the shaft of a mop, which serves as one bar of a prison cell composed of cleaning products. It’s an apt metaphor. In mid-century America, housewives were expected to polish their own gilded cages without considering how their feelings of entrapment might be related to their imprisonment in suburban homes. But by the late 1960s, even advertisers recognized that women might find such lives a little upsetting after reading The Feminine Mystique.

A woman gnaws at her nails: one hand in her mouth, the other clutching the shaft of a mop, which serves as one bar of a prison cell composed of cleaning products. It’s an apt metaphor. In mid-century America, housewives were expected to polish their own gilded cages without considering how their feelings of entrapment might be related to their imprisonment in suburban homes. But by the late 1960s, even advertisers recognized that women might find such lives a little upsetting after reading The Feminine Mystique. “We are all Sally Mann now,” one might think, gazing at the social-media streams that

“We are all Sally Mann now,” one might think, gazing at the social-media streams that  I’m sure it’s my interest in knowing what’s normal as much as my interest in porn that led me, a few months ago, to pick up a copy of Porn, by Polly Barton. Subtitled “an oral history” and put out by the highbrow independent press Fitzcarraldo Editions, Porn is billed on the back cover as a “thrilling, thought-provoking, revelatory, revealing, joyfully informative and informal exploration of a subject that has always retained an element of the taboo.” It’s organized as a series of “chats” between the author and nineteen acquaintances, varied across age and gender and anonymized so that each subject is referred to with a number from one to nineteen. Barton is a translator who found herself surprised by the realization that she wanted to write about the ever-present but largely unspoken subject of porn, so much so that the idea kept her up at night. This preoccupation felt “deeply embarrassing” to her: “If only I was a porn connoisseur,” she writes regretfully. Her “predominant feeling towards porn,” she continues in the introduction,

I’m sure it’s my interest in knowing what’s normal as much as my interest in porn that led me, a few months ago, to pick up a copy of Porn, by Polly Barton. Subtitled “an oral history” and put out by the highbrow independent press Fitzcarraldo Editions, Porn is billed on the back cover as a “thrilling, thought-provoking, revelatory, revealing, joyfully informative and informal exploration of a subject that has always retained an element of the taboo.” It’s organized as a series of “chats” between the author and nineteen acquaintances, varied across age and gender and anonymized so that each subject is referred to with a number from one to nineteen. Barton is a translator who found herself surprised by the realization that she wanted to write about the ever-present but largely unspoken subject of porn, so much so that the idea kept her up at night. This preoccupation felt “deeply embarrassing” to her: “If only I was a porn connoisseur,” she writes regretfully. Her “predominant feeling towards porn,” she continues in the introduction, Molly Moscatiello, age 7, started riding her bike to first grade last year. There’s a crosswalk with no crossing guard, “and I had to look both ways like five times,” she says, two grown-up teeth peeking through the gap in the front of her smile. Sometimes her parents’ friends would drive past and ask if Molly needed a ride, but she’d always wave them off. “I felt a little nervous at first,” she says. “But then after a while I felt comfortable by myself.” Soon, other kids began asking to ride their bikes to school. By the end of first grade, Molly was leading a small cohort of five or six, riding to school together in Little Silver, N.J.

Molly Moscatiello, age 7, started riding her bike to first grade last year. There’s a crosswalk with no crossing guard, “and I had to look both ways like five times,” she says, two grown-up teeth peeking through the gap in the front of her smile. Sometimes her parents’ friends would drive past and ask if Molly needed a ride, but she’d always wave them off. “I felt a little nervous at first,” she says. “But then after a while I felt comfortable by myself.” Soon, other kids began asking to ride their bikes to school. By the end of first grade, Molly was leading a small cohort of five or six, riding to school together in Little Silver, N.J. The cover of “Man’s Best Friend” features a photo of Carpenter wearing heels and a black cocktail dress, on her hands and knees, before a faceless man who clutches a fistful of her hair. The image consciously hints at porn (the set includes beige wall-to-wall carpeting and heavy white drapes, as if Carpenter were crawling through a Motel 6) and sexual submission, particularly when paired with the album’s title. Reactions were swift and high-pitched. People tend to find the union of sex and violence—or sex and willing subjugation—either fun and titillating or gruesome and catastrophically sinful.

The cover of “Man’s Best Friend” features a photo of Carpenter wearing heels and a black cocktail dress, on her hands and knees, before a faceless man who clutches a fistful of her hair. The image consciously hints at porn (the set includes beige wall-to-wall carpeting and heavy white drapes, as if Carpenter were crawling through a Motel 6) and sexual submission, particularly when paired with the album’s title. Reactions were swift and high-pitched. People tend to find the union of sex and violence—or sex and willing subjugation—either fun and titillating or gruesome and catastrophically sinful. It is hard to find a philosopher who writes well. One can list the good stylists on one hand:

It is hard to find a philosopher who writes well. One can list the good stylists on one hand:  In this clever book, Stuart Jeffries starts out at a double disadvantage, though. First: he has an excellently snappy title but it’s open to question whether stupidity can be said to have a history in any meaningful sense. The quality of stupidity is just, sort of, there; and there’s lots of it. Could you write a history of happiness, or bad luck, or knees? You’d be on firmer ground, as he recognises, historicising the concept of stupidity: a short history, in other words, of “stupidity” – how successive societies and thinkers have defined and responded to reason’s derr-brained secret sharer. As an intellectual historian who has written smart and chewy popular books about the Frankfurt School (Grand Hotel Abyss) and postmodernism (Everything, All the Time, Everywhere), he certainly has the chops for it.

In this clever book, Stuart Jeffries starts out at a double disadvantage, though. First: he has an excellently snappy title but it’s open to question whether stupidity can be said to have a history in any meaningful sense. The quality of stupidity is just, sort of, there; and there’s lots of it. Could you write a history of happiness, or bad luck, or knees? You’d be on firmer ground, as he recognises, historicising the concept of stupidity: a short history, in other words, of “stupidity” – how successive societies and thinkers have defined and responded to reason’s derr-brained secret sharer. As an intellectual historian who has written smart and chewy popular books about the Frankfurt School (Grand Hotel Abyss) and postmodernism (Everything, All the Time, Everywhere), he certainly has the chops for it. In 2025,

In 2025,  Every generation thinks it’s witnessing humanity’s moral collapse. New York Times columnist

Every generation thinks it’s witnessing humanity’s moral collapse. New York Times columnist