Rebecca Solnit in The Guardian:

Proclaiming what’s going to happen is a popular way to shrug off taking responsibility for helping to determine what’s going to happen. And it’s something we’ve seen a lot with doomspreading prophecies that Donald Trump is going to run for president or even win in 2024. One of the assumptions is that Trump will still be alive and competent to run, but the health of this sedentary shouter in his mid-70s, including the after-effects of the Covid-19 he was hospitalised for in 2020, could change. Look to external issues too, for whatever the condition of his own health, his financial health is under attack, with businesses losing money and some banks refusing to lend to him after the storming of the Capitol.

Proclaiming what’s going to happen is a popular way to shrug off taking responsibility for helping to determine what’s going to happen. And it’s something we’ve seen a lot with doomspreading prophecies that Donald Trump is going to run for president or even win in 2024. One of the assumptions is that Trump will still be alive and competent to run, but the health of this sedentary shouter in his mid-70s, including the after-effects of the Covid-19 he was hospitalised for in 2020, could change. Look to external issues too, for whatever the condition of his own health, his financial health is under attack, with businesses losing money and some banks refusing to lend to him after the storming of the Capitol.

It’s also worth remembering that he lost the popular vote by millions in 2016 and by more millions in 2020; he never had a mandate. The Republicans are clearly gearing up to try to steal an election again, but their chances of winning one with Trump as candidate seem slim. Currently, he is creating conflict within the Republican party with his insistence on controlling it for his own agenda and punishing dissenters.

More here.

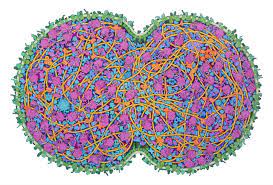

It was by accident that Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, a Dutch cloth merchant, first saw a living cell. He’d begun making magnifying lenses at home, perhaps to better judge the quality of his cloth. One day, out of curiosity, he held one up to a drop of lake water. He saw that the drop was teeming with numberless tiny animals. These animalcules, as he called them, were everywhere he looked—in the stuff between his teeth, in soil, in food gone bad. A decade earlier, in 1665, an Englishman named Robert Hooke had examined cork through a lens; he’d found structures that he called “cells,” and the name had stuck. Van Leeuwenhoek seemed to see an even more striking view: his cells moved with apparent purpose. No one believed him when he told people what he’d discovered, and he had to ask local bigwigs—the town priest, a notary, a lawyer—to peer through his lenses and attest to what they saw.

It was by accident that Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, a Dutch cloth merchant, first saw a living cell. He’d begun making magnifying lenses at home, perhaps to better judge the quality of his cloth. One day, out of curiosity, he held one up to a drop of lake water. He saw that the drop was teeming with numberless tiny animals. These animalcules, as he called them, were everywhere he looked—in the stuff between his teeth, in soil, in food gone bad. A decade earlier, in 1665, an Englishman named Robert Hooke had examined cork through a lens; he’d found structures that he called “cells,” and the name had stuck. Van Leeuwenhoek seemed to see an even more striking view: his cells moved with apparent purpose. No one believed him when he told people what he’d discovered, and he had to ask local bigwigs—the town priest, a notary, a lawyer—to peer through his lenses and attest to what they saw. No clear genetic origin has been found for stuttering, and neither have emotional origins like trauma been ruled out. Still there is no cure. Some techniques work for some stutterers, some of the time. A hundred years ago doctors tried cutting out portions of the tongues of stutterers, killing and maiming many, curing none. Online, there are testimonies from people who swear by certain techniques, people who are taking Vitamin B1, people who are gloriously fluent, and people in the midst of a tough recurrence.

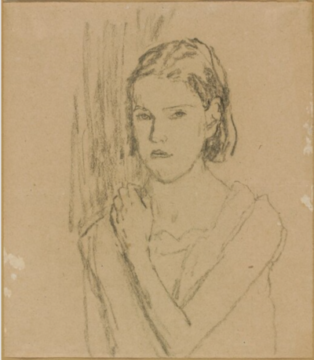

No clear genetic origin has been found for stuttering, and neither have emotional origins like trauma been ruled out. Still there is no cure. Some techniques work for some stutterers, some of the time. A hundred years ago doctors tried cutting out portions of the tongues of stutterers, killing and maiming many, curing none. Online, there are testimonies from people who swear by certain techniques, people who are taking Vitamin B1, people who are gloriously fluent, and people in the midst of a tough recurrence. Such sexually explicit content became what Templeton was best known for during her lifetime—a reputation made yet more notorious due to the fact that she drew direct inspiration from her own illicit trysts. She was born into a wealthy upper-class family in Prague in 1916, and raised in a world of sophistication, civility, and gentility: this social milieu would have been shocked by such self-exposing erotica. Edith Passerová, as she was then, met her first husband, the Englishman William Stockwell Templeton, when she was only seventeen. They married five years later, in 1938, and lived in England. The union quickly disintegrated, but rather than return home to what by that point was a war-torn Europe, Templeton remained in Britain after their separation. She initially took a job with the American War Office, during which time she had the brief fling described in “The Darts of Cupid.” The story’s candid, violently charged eroticism caused a stir when it was first published in The New Yorker, but even its level of graphic sexual detail paled in comparison to that of Templeton’s most famous novel.

Such sexually explicit content became what Templeton was best known for during her lifetime—a reputation made yet more notorious due to the fact that she drew direct inspiration from her own illicit trysts. She was born into a wealthy upper-class family in Prague in 1916, and raised in a world of sophistication, civility, and gentility: this social milieu would have been shocked by such self-exposing erotica. Edith Passerová, as she was then, met her first husband, the Englishman William Stockwell Templeton, when she was only seventeen. They married five years later, in 1938, and lived in England. The union quickly disintegrated, but rather than return home to what by that point was a war-torn Europe, Templeton remained in Britain after their separation. She initially took a job with the American War Office, during which time she had the brief fling described in “The Darts of Cupid.” The story’s candid, violently charged eroticism caused a stir when it was first published in The New Yorker, but even its level of graphic sexual detail paled in comparison to that of Templeton’s most famous novel. A week ago I unrestrainedly used the phrase Слава Україні!/Glory to Ukraine!, and a few friends and readers were surprised to see me resorting to jingoism, even if for a country not my own. This struck some as particularly inadvisable, since the phrase is associated in some of its expressions with far-right Ukrainian nationalism, and with the handful of people in Ukraine who minimally justify Putin’s claim to be undertaking a campaign of “de-Nazification” there. The first time I used the phrase was in 2014, at a rally in Paris in support of the Maidan demonstrators in Kyiv, among a Ukrainian diaspora that was resolutely pro-democracy and worlds away from any far-right sentiments. But a rally is one thing, an essay another, and as the week wore on I admit my use of the phrase echoed in my mind, and came to feel increasingly like a mistake.

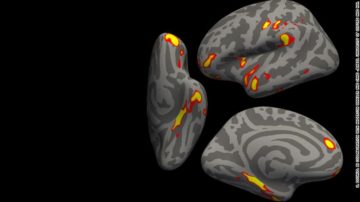

A week ago I unrestrainedly used the phrase Слава Україні!/Glory to Ukraine!, and a few friends and readers were surprised to see me resorting to jingoism, even if for a country not my own. This struck some as particularly inadvisable, since the phrase is associated in some of its expressions with far-right Ukrainian nationalism, and with the handful of people in Ukraine who minimally justify Putin’s claim to be undertaking a campaign of “de-Nazification” there. The first time I used the phrase was in 2014, at a rally in Paris in support of the Maidan demonstrators in Kyiv, among a Ukrainian diaspora that was resolutely pro-democracy and worlds away from any far-right sentiments. But a rally is one thing, an essay another, and as the week wore on I admit my use of the phrase echoed in my mind, and came to feel increasingly like a mistake. People who have even a mild case of Covid-19 may have accelerated aging of the brain and other changes to it, according to a new study.

People who have even a mild case of Covid-19 may have accelerated aging of the brain and other changes to it, according to a new study. Morgan Meis (MM): Jed, your new book, Authority and Freedom*, has come out in the last few weeks. Congratulations! In it, right near the end, you give this lovely quote from WH Auden, from his poem about Yeats:

Morgan Meis (MM): Jed, your new book, Authority and Freedom*, has come out in the last few weeks. Congratulations! In it, right near the end, you give this lovely quote from WH Auden, from his poem about Yeats: Thursday morning, after the publication of

Thursday morning, after the publication of  The mission to turn space into the next frontier for express deliveries took off from a modest propeller plane above a remote airstrip in the shadow of the Santa Ana mountains. Shortly after sunrise on a recent Saturday, an engineer for Inversion Space, a start-up that’s barely a year old, tossed a capsule resembling a flying saucer out the open door of an aircraft flying at 3,000 feet. The capsule, 20 inches in diameter, somersaulted in the air for a few seconds before a parachute deployed and snapped the container upright for a slow descent. “It was slow to open,” said Justin Fiaschetti, Inversion’s 23-year-old chief executive, who anxiously watched the parachute through the viewfinder of a camera with a long lens.

The mission to turn space into the next frontier for express deliveries took off from a modest propeller plane above a remote airstrip in the shadow of the Santa Ana mountains. Shortly after sunrise on a recent Saturday, an engineer for Inversion Space, a start-up that’s barely a year old, tossed a capsule resembling a flying saucer out the open door of an aircraft flying at 3,000 feet. The capsule, 20 inches in diameter, somersaulted in the air for a few seconds before a parachute deployed and snapped the container upright for a slow descent. “It was slow to open,” said Justin Fiaschetti, Inversion’s 23-year-old chief executive, who anxiously watched the parachute through the viewfinder of a camera with a long lens. The heliostats will reflect the sun’s rays onto a tall, mirror-covered tower to be set in the center of town. In turn, the tower will deflect the light onto other mirrors mounted on building facades, diffusing the beams to prevent dangerously focused, scorching rays. The mirrors will not drench the town in an even, blinding glare; this is no movie set where, with the flip of a switch and a dozen flood bulbs, night dazzlingly becomes day. (Such broad, total illumination would require impossibly enormous mirrors.) Instead, light will cascade down to create areas of illumination, or “hotspots.” Preliminary sketches reveal a pleasantly dappled effect, not unlike the sun-speckled lanes of Thomas Kinkade paintings. These bright spots, however, will be about “lawn size,” large enough for people to cluster inside, like fish schooling in shimmering pools of sunshine.

The heliostats will reflect the sun’s rays onto a tall, mirror-covered tower to be set in the center of town. In turn, the tower will deflect the light onto other mirrors mounted on building facades, diffusing the beams to prevent dangerously focused, scorching rays. The mirrors will not drench the town in an even, blinding glare; this is no movie set where, with the flip of a switch and a dozen flood bulbs, night dazzlingly becomes day. (Such broad, total illumination would require impossibly enormous mirrors.) Instead, light will cascade down to create areas of illumination, or “hotspots.” Preliminary sketches reveal a pleasantly dappled effect, not unlike the sun-speckled lanes of Thomas Kinkade paintings. These bright spots, however, will be about “lawn size,” large enough for people to cluster inside, like fish schooling in shimmering pools of sunshine. The word “salon,” for a starry convocation of creative types, intelligentsia, and patrons, has never firmly penetrated English. It retains a pair of transatlantic wet feet from the phenomenon’s storied annals, chiefly in France, since the eighteenth century. So it was that the all-time most glamorous and consequential American instance, thriving in New York between 1915 and 1920, centered on Europeans in temporary flight from the miseries of the First World War. Their hosts were Walter Arensberg, a Pittsburgh steel heir, and his wife, Louise Stevens, an even wealthier Massachusetts textile-industry legatee. The couple had been thunderstruck by the 1913 Armory Show of international contemporary art, which exposed Americans to Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and, in particular, Marcel Duchamp. Made the previous year, his painting “Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2),” a cunning mashup of Cubism and Futurism, with its title hand-lettered along the bottom, was the event’s prime sensation: at once insinuating indecency and making it hard to perceive, what with the image’s scalloped planes, which a Times critic jovially likened to “an explosion in a shingle factory.”

The word “salon,” for a starry convocation of creative types, intelligentsia, and patrons, has never firmly penetrated English. It retains a pair of transatlantic wet feet from the phenomenon’s storied annals, chiefly in France, since the eighteenth century. So it was that the all-time most glamorous and consequential American instance, thriving in New York between 1915 and 1920, centered on Europeans in temporary flight from the miseries of the First World War. Their hosts were Walter Arensberg, a Pittsburgh steel heir, and his wife, Louise Stevens, an even wealthier Massachusetts textile-industry legatee. The couple had been thunderstruck by the 1913 Armory Show of international contemporary art, which exposed Americans to Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and, in particular, Marcel Duchamp. Made the previous year, his painting “Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2),” a cunning mashup of Cubism and Futurism, with its title hand-lettered along the bottom, was the event’s prime sensation: at once insinuating indecency and making it hard to perceive, what with the image’s scalloped planes, which a Times critic jovially likened to “an explosion in a shingle factory.” For one thing, it is not nearly as newfangled as we usually conceive of it. It does not represent a radical rupture with everything that came before, either in human history or in the vastly longer history of nature that precedes the first appearance of our species. It is, rather, only the most recent permutation of a complex of behaviors that is as deeply rooted in who we are as a species as anything else we do: our storytelling, our fashions, our friendships; our evolution as beings that inhabit a universe dense with symbols.

For one thing, it is not nearly as newfangled as we usually conceive of it. It does not represent a radical rupture with everything that came before, either in human history or in the vastly longer history of nature that precedes the first appearance of our species. It is, rather, only the most recent permutation of a complex of behaviors that is as deeply rooted in who we are as a species as anything else we do: our storytelling, our fashions, our friendships; our evolution as beings that inhabit a universe dense with symbols. Deep time is, to me, one of the most awe-inspiring concepts to come out of the earth sciences. Getting to grips with the incomprehensibly vast stretches of time over which geological processes play out is not easy. We are,

Deep time is, to me, one of the most awe-inspiring concepts to come out of the earth sciences. Getting to grips with the incomprehensibly vast stretches of time over which geological processes play out is not easy. We are,  On his daily podcast, the conservative commentator and #NeverTrumper Charlie Sykes often refers to Donald Trump as “the orange god-king” and to the former president’s fervent MAGA following as a “cult.” The jibe may be intended for laughs, but it hints at a deeper truth: The neoauthoritarian leaders of the present era have more than a little in common with the divine kings of the ancient world, and the enchanted worldviews of those who follow Donald Trump and others like him often verge on premodern magical thinking. In this respect, Trump and Trumpism are but one example of a global phenomenon, with similar figures and their similarly devout followers everywhere from Russia, Hungary, and Turkey to Brazil, the Philippines, and—possibly, with its own special characteristics—the new-old Middle Kingdom of the People’s Republic of China.

On his daily podcast, the conservative commentator and #NeverTrumper Charlie Sykes often refers to Donald Trump as “the orange god-king” and to the former president’s fervent MAGA following as a “cult.” The jibe may be intended for laughs, but it hints at a deeper truth: The neoauthoritarian leaders of the present era have more than a little in common with the divine kings of the ancient world, and the enchanted worldviews of those who follow Donald Trump and others like him often verge on premodern magical thinking. In this respect, Trump and Trumpism are but one example of a global phenomenon, with similar figures and their similarly devout followers everywhere from Russia, Hungary, and Turkey to Brazil, the Philippines, and—possibly, with its own special characteristics—the new-old Middle Kingdom of the People’s Republic of China.