Hannah Fish in The Christian Science Monitor:

On Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, rests an extraordinary monument that has puzzled and inspired people for millennia: the circular set of rocks known as Stonehenge. The iconic scene, so precisely designed and constructed, provokes a litany of questions: What motivated the Neolithic people to create such a thing? Where did the huge, 20-ton stones come from? How was it built?

On Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, rests an extraordinary monument that has puzzled and inspired people for millennia: the circular set of rocks known as Stonehenge. The iconic scene, so precisely designed and constructed, provokes a litany of questions: What motivated the Neolithic people to create such a thing? Where did the huge, 20-ton stones come from? How was it built?

Archaeologist and journalist Mike Pitts, who has studied the ruins for decades and co-directed excavations at the site, offers readers an in-depth assessment in “How To Build Stonehenge.” While he doesn’t try to answer the first question of why – writing that “imagination is the only limit” to finding a motive – he does break down the second question into several components: how the stones were obtained, how they were moved to the site, how the structure was erected, and how its construction has changed over time. Overall, the book feels geared toward readers who relish granular technicalities of geological analysis. Yet for those who are more interested in the human aspects of Stonehenge’s construction, Pitts’ review of how megaliths have been handled over time still proves noteworthy.

For example, studies have identified the Preseli Hills in Pembrokeshire, Wales, as the place where the smaller ring of rocks known as bluestones were quarried. The bluestones, which weigh an average of 2 tons apiece, were somehow transported to Salisbury Plain, which lies 140 miles from the Preseli Hills. (By comparison, the larger slabs, known as sarsens, weigh 20 tons and are thought to have come from Marlborough Downs, about 20 miles north of Stonehenge.) To begin to understand how the bluestones could have been moved such a distance, Pitts turns to another corner of the globe: the Indian Ocean.

More here.

Juneteenth — a portmanteau of “June” and “nineteenth” — became a federal holiday just last year, but Black Americans, particularly Black Texans, have been celebrating it for generations. The first Juneteenth festivities took place in the late 19th century in Texas’s Emancipation Park, and combined

Juneteenth — a portmanteau of “June” and “nineteenth” — became a federal holiday just last year, but Black Americans, particularly Black Texans, have been celebrating it for generations. The first Juneteenth festivities took place in the late 19th century in Texas’s Emancipation Park, and combined  They are the ultimate “how to draw” books for a young child, created by a doting dad who just happened to be one of the greatest artists of the 20th century. The granddaughter of

They are the ultimate “how to draw” books for a young child, created by a doting dad who just happened to be one of the greatest artists of the 20th century. The granddaughter of  The day an asteroid slammed into the Yucatán Peninsula some 66 million years ago is a strong contender for “the worst day in history”. The K–Pg extinction ended the long evolutionary success story of the dinosaurs and a host of other creatures, and has lodged itself firmly in our collective imagination. But what happened next? The fact that a primate is tapping away at a keyboard writing this review gives you part of the answer. The rise of mammals was not a given, though, and the details have been hard to get by. Here, science writer Riley Black examines and imagines the aftermath of the extinction at various times post-impact. The Last Days of the Dinosaurs ends up being a fine piece of narrative non-fiction with thoughtful observations on the role of evolution in ecosystem recovery.

The day an asteroid slammed into the Yucatán Peninsula some 66 million years ago is a strong contender for “the worst day in history”. The K–Pg extinction ended the long evolutionary success story of the dinosaurs and a host of other creatures, and has lodged itself firmly in our collective imagination. But what happened next? The fact that a primate is tapping away at a keyboard writing this review gives you part of the answer. The rise of mammals was not a given, though, and the details have been hard to get by. Here, science writer Riley Black examines and imagines the aftermath of the extinction at various times post-impact. The Last Days of the Dinosaurs ends up being a fine piece of narrative non-fiction with thoughtful observations on the role of evolution in ecosystem recovery. WHEN THE FILM VERSION

WHEN THE FILM VERSION

“Crops were planted on 1.371 billion hectares (3.387 billion acres) globally in 1961. That rose to 1.533 billion hectares (3.788 billion acres) in 2009. Ausubel and his coauthors project a return to 1.385 billion hectares (3.422 billion acres) in 2060, thus restoring at least 146 million hectares (360 million acres) to nature. This is an area two and a half times that of France, or the size of 10 Iowas. Although cropland has continued to expand slowly since 2009, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization reports that land devoted to agriculture (including pastures) peaked in 2000 at 4915 billion hectares (12.15 billion acres) and had fallen to 4.828 billion hectares (1193 bill on acres) by 2017. The human withdrawal from the landscape is the likely prelude to a vast ecological restoration over the course of this century.

“Crops were planted on 1.371 billion hectares (3.387 billion acres) globally in 1961. That rose to 1.533 billion hectares (3.788 billion acres) in 2009. Ausubel and his coauthors project a return to 1.385 billion hectares (3.422 billion acres) in 2060, thus restoring at least 146 million hectares (360 million acres) to nature. This is an area two and a half times that of France, or the size of 10 Iowas. Although cropland has continued to expand slowly since 2009, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization reports that land devoted to agriculture (including pastures) peaked in 2000 at 4915 billion hectares (12.15 billion acres) and had fallen to 4.828 billion hectares (1193 bill on acres) by 2017. The human withdrawal from the landscape is the likely prelude to a vast ecological restoration over the course of this century. Vladimir Nabokov’s 1955 novel Lolita still attracts plenty of analysis, admiration and disgust, in the classroom and beyond. But despite the pedigree of the beloved film-maker Stanley Kubrick, the first film adaptation of Lolita – released 60 years ago this week – is arguably more of a curio these days, forced to excise or elide some of the book’s thorniest elements for the sake of being allowed to exist at all.

Vladimir Nabokov’s 1955 novel Lolita still attracts plenty of analysis, admiration and disgust, in the classroom and beyond. But despite the pedigree of the beloved film-maker Stanley Kubrick, the first film adaptation of Lolita – released 60 years ago this week – is arguably more of a curio these days, forced to excise or elide some of the book’s thorniest elements for the sake of being allowed to exist at all. He

He  The House select committee investigating the

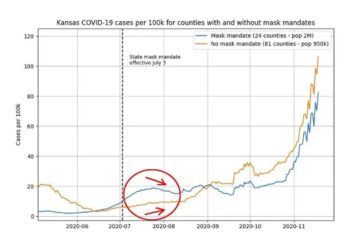

The House select committee investigating the  The main federal agency guiding America’s pandemic policy is the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, which sets widely adopted policies on masking, vaccination, distancing, and other mitigation efforts to slow the spread of COVID and ensure the virus is less morbid when it leads to infection. The CDC is, in part, a scientific agency—they use facts and principles of science to guide policy—but they are also fundamentally a political agency: The director is appointed by the president of the United States, and the CDC’s guidance often balances public health and welfare with other priorities of the executive branch.

The main federal agency guiding America’s pandemic policy is the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, which sets widely adopted policies on masking, vaccination, distancing, and other mitigation efforts to slow the spread of COVID and ensure the virus is less morbid when it leads to infection. The CDC is, in part, a scientific agency—they use facts and principles of science to guide policy—but they are also fundamentally a political agency: The director is appointed by the president of the United States, and the CDC’s guidance often balances public health and welfare with other priorities of the executive branch. By this point, the enlightened reader may well be wondering whether anything of value can be salvaged from this full-blooded reactionary. The answer is surely affirmative. For one thing, Eliot’s elitism, demeaning estimate of humanity, and indiscriminate distaste for modern civilization are the stock in trade of the so-called Kulturkritik tradition that he inherited. Many an eminent twentieth-century intellectual held views of this kind, and so did a sizeable proportion of the Western population of the time. This doesn’t excuse their attitudes, but it helps explain them. For another thing, such attitudes put Eliot at loggerheads with the liberal-capitalist ideology of his age. He is, in short, a radical of the right, like a large number of his fellow modernists. He believes in the importance of communal bonds, as much liberal ideology does not; he also rejects capitalism’s greed, selfish individualism, and pursuit of material self-interest. “The organization of society on the principle of private profit,” he writes in The Idea of a Christian Society, “as well as public destruction, is leading both to the deformation of humanity by unregulated industrialism, and so to the exhaustion of natural resources…a good deal of our material progress is a progress for which succeeding generations may have to pay dearly.”

By this point, the enlightened reader may well be wondering whether anything of value can be salvaged from this full-blooded reactionary. The answer is surely affirmative. For one thing, Eliot’s elitism, demeaning estimate of humanity, and indiscriminate distaste for modern civilization are the stock in trade of the so-called Kulturkritik tradition that he inherited. Many an eminent twentieth-century intellectual held views of this kind, and so did a sizeable proportion of the Western population of the time. This doesn’t excuse their attitudes, but it helps explain them. For another thing, such attitudes put Eliot at loggerheads with the liberal-capitalist ideology of his age. He is, in short, a radical of the right, like a large number of his fellow modernists. He believes in the importance of communal bonds, as much liberal ideology does not; he also rejects capitalism’s greed, selfish individualism, and pursuit of material self-interest. “The organization of society on the principle of private profit,” he writes in The Idea of a Christian Society, “as well as public destruction, is leading both to the deformation of humanity by unregulated industrialism, and so to the exhaustion of natural resources…a good deal of our material progress is a progress for which succeeding generations may have to pay dearly.”