Sam Fowles in The Guardian:

Truth is democracy’s most important moral value. We work out our direction, as a society, through public discourse. Power and wealth confer an advantage in this: the more people you can reach (by virtue of enjoying easy access to the media, or even controlling sections of it), the more likely you are to bring others round to your point of view. The rich and powerful may be able to reach more people but, if their arguments are required to conform to reality, we can at least hold them to account. Truth is a great leveller.

Truth is democracy’s most important moral value. We work out our direction, as a society, through public discourse. Power and wealth confer an advantage in this: the more people you can reach (by virtue of enjoying easy access to the media, or even controlling sections of it), the more likely you are to bring others round to your point of view. The rich and powerful may be able to reach more people but, if their arguments are required to conform to reality, we can at least hold them to account. Truth is a great leveller.

The problem is that our public discourse has become increasingly divorced from reality. The pollster Ipsos Mori conducts regular surveys on what the British public believes about the facts behind frequently discussed issues. In one memorable study it discovered that, in the words of one headline, “the British public is wrong about nearly everything”. Among the concerns was benefit fraud: people surveyed estimated that around £24 of every £100 of benefits was fraudulently claimed, whereas the actual figure was 70p. When asked about immigration, people estimated that 31% of the population were born outside the UK, when in truth it was 13%.

Members of parliament have played a prominent role in getting us to this point.

More here.

It was 3 a.m. I was exhausted from taking care of my 3-month-old baby, but I couldn’t sleep. As I tried to recall the topics of the five conference calls on my calendar for the morning, I again had the haunting thought that I wasn’t good enough for my job—a director position I started shortly before my baby was born. I imagined I would make mistakes in my presentations and my team would lose respect for me. Tormented by these thoughts, I reached for a book from the pile on my bedside table to distract myself. By chance I grabbed the Bible, which I had been too busy to read since my baby was born. As I opened it to a random page and happened on the verse “For when I am weak, then I am strong,” tears filled my eyes, and I could breathe again.

It was 3 a.m. I was exhausted from taking care of my 3-month-old baby, but I couldn’t sleep. As I tried to recall the topics of the five conference calls on my calendar for the morning, I again had the haunting thought that I wasn’t good enough for my job—a director position I started shortly before my baby was born. I imagined I would make mistakes in my presentations and my team would lose respect for me. Tormented by these thoughts, I reached for a book from the pile on my bedside table to distract myself. By chance I grabbed the Bible, which I had been too busy to read since my baby was born. As I opened it to a random page and happened on the verse “For when I am weak, then I am strong,” tears filled my eyes, and I could breathe again. While the question of alien life is never far from our investigations of distant galactic structures, the device’s distinctive honeycomb structure seems emblematic of the organic complexity of our own planet, of what it has been capable of producing, and what it is capable of projecting out into space.

While the question of alien life is never far from our investigations of distant galactic structures, the device’s distinctive honeycomb structure seems emblematic of the organic complexity of our own planet, of what it has been capable of producing, and what it is capable of projecting out into space. The intuition that language might simply be memorized has some superficial plausibility – but only if you restrict your focus to simple concrete nouns like ball and bottle. A child looks at a bottle, mama says bottle, and child associates the word bottle with the concept BOTTLE. Some tiny fragment of language may be learned this way. But this simple learning by pointing-plus-naming idea, as intuitive as it is, doesn’t get you very far.

The intuition that language might simply be memorized has some superficial plausibility – but only if you restrict your focus to simple concrete nouns like ball and bottle. A child looks at a bottle, mama says bottle, and child associates the word bottle with the concept BOTTLE. Some tiny fragment of language may be learned this way. But this simple learning by pointing-plus-naming idea, as intuitive as it is, doesn’t get you very far. Modern politics has always been replete with issues about which people feel passionate, sometimes aggressively so. But the culture wars currently raging in the US, Canada, and across much of the industrialized West seem to be particularly fraught. In my 50-plus years, I have never seen so much anger and hostility among citizens of otherwise stable countries. Some of these people will participate in protests or engage in civil disobedience, but many more will employ the political meme to express their discontent. Given how widespread the phenomenon has become, it’s worth asking whether political memes actually advance advocacy goals and our knowledge of important issues, or if they simply feed an unconstructive cycle of anger, misinformation, and polarization.

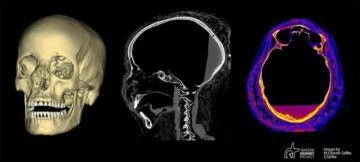

Modern politics has always been replete with issues about which people feel passionate, sometimes aggressively so. But the culture wars currently raging in the US, Canada, and across much of the industrialized West seem to be particularly fraught. In my 50-plus years, I have never seen so much anger and hostility among citizens of otherwise stable countries. Some of these people will participate in protests or engage in civil disobedience, but many more will employ the political meme to express their discontent. Given how widespread the phenomenon has become, it’s worth asking whether political memes actually advance advocacy goals and our knowledge of important issues, or if they simply feed an unconstructive cycle of anger, misinformation, and polarization. A team of researchers with the Warsaw Mummy Project, has announced on their

A team of researchers with the Warsaw Mummy Project, has announced on their  In 1838, Charles Darwin faced a problem. Nearing his 30th birthday, he was trying to decide whether to marry — with the likelihood that children would be part of the package. To help make his decision, Darwin

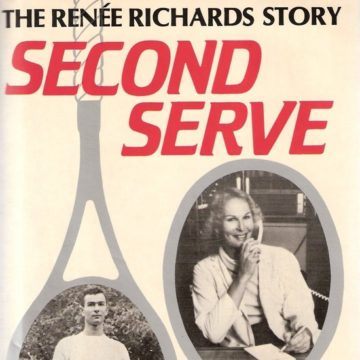

In 1838, Charles Darwin faced a problem. Nearing his 30th birthday, he was trying to decide whether to marry — with the likelihood that children would be part of the package. To help make his decision, Darwin  RENÉE RICHARDS, eighty-seven, has admitted she has some regrets. Among them is that she never pitched for the New York Yankees, a job MLB scouts once seemed to think she had a real shot at.

RENÉE RICHARDS, eighty-seven, has admitted she has some regrets. Among them is that she never pitched for the New York Yankees, a job MLB scouts once seemed to think she had a real shot at.

Louis Rogers in Sidecar (image by

Louis Rogers in Sidecar (image by

So now we can answer the question: How does democracy die? It dies not in darkness, as the Washington Post’s Trump-era slogan would have it, but in the White House itself, in the private dining room off the Oval Office, with the sound of Fox News blaring in the background. That private dining room was

So now we can answer the question: How does democracy die? It dies not in darkness, as the Washington Post’s Trump-era slogan would have it, but in the White House itself, in the private dining room off the Oval Office, with the sound of Fox News blaring in the background. That private dining room was