Rana Foroohar in Foreign Affairs:

For most of the last 40 years, U.S. policymakers acted as if the world were flat. Steeped in the dominant strain of neoliberal economic thinking, they assumed that capital, goods, and people would go wherever they would be the most productive for everyone. If companies created jobs overseas, where it was cheapest to do so, domestic employment losses would be outweighed by consumer benefits. And if governments lowered trade barriers and deregulated capital markets, money would flow where it was needed most. Policymakers didn’t have to take geography into account, since the invisible hand was at work everywhere. Place, in other words, didn’t matter.

For most of the last 40 years, U.S. policymakers acted as if the world were flat. Steeped in the dominant strain of neoliberal economic thinking, they assumed that capital, goods, and people would go wherever they would be the most productive for everyone. If companies created jobs overseas, where it was cheapest to do so, domestic employment losses would be outweighed by consumer benefits. And if governments lowered trade barriers and deregulated capital markets, money would flow where it was needed most. Policymakers didn’t have to take geography into account, since the invisible hand was at work everywhere. Place, in other words, didn’t matter.

U.S. administrations from both parties have until quite recently pursued policies based on these broad assumptions—deregulating global finance, striking trade deals such as the North American Free Trade Agreement, welcoming China into the World Trade Organization (WTO), and not only allowing but encouraging American manufacturers to move much of their production overseas.

More here.

Perched on a leaf in the rainforest, the tiny golden mantella frog harbors a secret. It shares that secret with the fork-tongued frog, the reed frog and myriad other frogs in the hills and forests of the island nation of Madagascar, as well as with the boas and other snakes that prey on them. On this island, many of whose animal species occur nowhere else, geneticists recently made a surprising discovery: Sprinkled through the genomes of the frogs is a gene, BovB, that seemingly came from snakes.

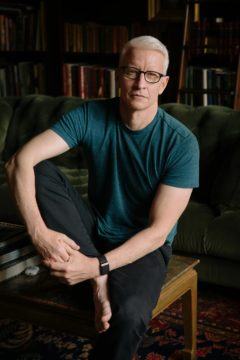

Perched on a leaf in the rainforest, the tiny golden mantella frog harbors a secret. It shares that secret with the fork-tongued frog, the reed frog and myriad other frogs in the hills and forests of the island nation of Madagascar, as well as with the boas and other snakes that prey on them. On this island, many of whose animal species occur nowhere else, geneticists recently made a surprising discovery: Sprinkled through the genomes of the frogs is a gene, BovB, that seemingly came from snakes. When the CNN anchor Anderson Cooper was ten, he lost his father, Wyatt, to heart disease; when he was twenty-one, his older brother Carter died by suicide. In 2019, his mother, the artist and clothing designer Gloria Vanderbilt, passed away at ninety-five, of stomach cancer. (Vanderbilt had watched, desperate and helpless, as Carter leapt from the terrace of the family’s fourteenth-floor apartment in Manhattan.) For Cooper, who is now fifty-five, loss has become an unexpected beacon in his life—a way of constantly reaffirming his humanity. “My mom and I would talk about this a lot,” Cooper said recently. “No matter what you’re going through, there are millions of people who have gone through far worse. It helps me to know this is a road that has been well travelled.”

When the CNN anchor Anderson Cooper was ten, he lost his father, Wyatt, to heart disease; when he was twenty-one, his older brother Carter died by suicide. In 2019, his mother, the artist and clothing designer Gloria Vanderbilt, passed away at ninety-five, of stomach cancer. (Vanderbilt had watched, desperate and helpless, as Carter leapt from the terrace of the family’s fourteenth-floor apartment in Manhattan.) For Cooper, who is now fifty-five, loss has become an unexpected beacon in his life—a way of constantly reaffirming his humanity. “My mom and I would talk about this a lot,” Cooper said recently. “No matter what you’re going through, there are millions of people who have gone through far worse. It helps me to know this is a road that has been well travelled.” T

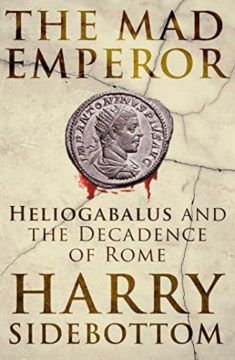

T These tales of flower petal asphyxiation and macrophallocracy are entertaining, but are they true? The source material is famously unreliable. One of the most raucous accounts, the late fourth-century Augustan History, is for the greater part a work of creative fiction. In recent years the academic fashion has been to treat all of the written sources on Heliogabalus with extreme scepticism, and to doubt whether very much at all can be known about him. The author of this new biography, Harry Sidebottom, who is both a historical novelist and an Oxford classics don, pushes against this trend. His account, which combines down-to-earth scholarly rigour with highly entertaining storytelling, critiques a number of received academic ideas. For example, he denies the notion that successive Roman emperors created an ‘official narrative’ hostile to Heliogabalus that was then parroted by contemporary historical writers. He also argues that just because the reports of the emperor’s actions echo those relating to a predecessor and thus appear to be topoi, or literary commonplaces, does not necessarily mean that they are untrue.

These tales of flower petal asphyxiation and macrophallocracy are entertaining, but are they true? The source material is famously unreliable. One of the most raucous accounts, the late fourth-century Augustan History, is for the greater part a work of creative fiction. In recent years the academic fashion has been to treat all of the written sources on Heliogabalus with extreme scepticism, and to doubt whether very much at all can be known about him. The author of this new biography, Harry Sidebottom, who is both a historical novelist and an Oxford classics don, pushes against this trend. His account, which combines down-to-earth scholarly rigour with highly entertaining storytelling, critiques a number of received academic ideas. For example, he denies the notion that successive Roman emperors created an ‘official narrative’ hostile to Heliogabalus that was then parroted by contemporary historical writers. He also argues that just because the reports of the emperor’s actions echo those relating to a predecessor and thus appear to be topoi, or literary commonplaces, does not necessarily mean that they are untrue. For decades, visions of possible climate futures have been anchored by, on the one hand, Pollyanna-like faith that normality would endure, and on the other, millenarian intuitions of an ecological end of days, during which perhaps billions of lives would be devastated or destroyed. More recently, these two stories have been mapped onto climate modeling: Conventional wisdom has dictated that meeting the most ambitious goals of the Paris agreement by limiting warming to 1.5 degrees could allow for some continuing normal, but failing to take rapid action on emissions, and allowing warming above three or even four degrees, spelled doom.

For decades, visions of possible climate futures have been anchored by, on the one hand, Pollyanna-like faith that normality would endure, and on the other, millenarian intuitions of an ecological end of days, during which perhaps billions of lives would be devastated or destroyed. More recently, these two stories have been mapped onto climate modeling: Conventional wisdom has dictated that meeting the most ambitious goals of the Paris agreement by limiting warming to 1.5 degrees could allow for some continuing normal, but failing to take rapid action on emissions, and allowing warming above three or even four degrees, spelled doom. Defenders of the Amazon rainforest were overwhelmed with relief on 30 October as Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva narrowly secured Brazil’s presidency.

Defenders of the Amazon rainforest were overwhelmed with relief on 30 October as Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva narrowly secured Brazil’s presidency. THE SUN IS BARELY VISIBLE

THE SUN IS BARELY VISIBLE  As a teenager growing up in Peckham, an ethnically diverse area of London, the photographer Nadine Ijewere observed the way that the women around her dressed. The neighbourhood “aunties”, as all older women were known, paired Nigerian patterns with Gucci handbags and Burberry motifs; they would

As a teenager growing up in Peckham, an ethnically diverse area of London, the photographer Nadine Ijewere observed the way that the women around her dressed. The neighbourhood “aunties”, as all older women were known, paired Nigerian patterns with Gucci handbags and Burberry motifs; they would  A new national study has suggested that chemical hair straighteners could pose a

A new national study has suggested that chemical hair straighteners could pose a  Twitter is a disaster clown car company that is successful despite itself, and there is no possible way to grow users and revenue without making a series of enormous compromises that will ultimately destroy your reputation and possibly cause grievous damage to your other companies.

Twitter is a disaster clown car company that is successful despite itself, and there is no possible way to grow users and revenue without making a series of enormous compromises that will ultimately destroy your reputation and possibly cause grievous damage to your other companies. Lorraine Daston: You’re right about the contraction of the expansiveness of “science,” which in all the European languages that derived some cognate from the Latin scientia used to refer to any form of organized knowledge. But it contracts not only in English but also in French, albeit a bit later in the late nineteenth and the early twentieth century. The French term for the scientist or scholar goes from being savant, which is still a word you can easily encounter in nineteenth-century French, to scientifique to refer exclusively to a scientist. And it surely has to do with the soaring prestige of the natural sciences, which is also the case in Germany.

Lorraine Daston: You’re right about the contraction of the expansiveness of “science,” which in all the European languages that derived some cognate from the Latin scientia used to refer to any form of organized knowledge. But it contracts not only in English but also in French, albeit a bit later in the late nineteenth and the early twentieth century. The French term for the scientist or scholar goes from being savant, which is still a word you can easily encounter in nineteenth-century French, to scientifique to refer exclusively to a scientist. And it surely has to do with the soaring prestige of the natural sciences, which is also the case in Germany. A juvenile

A juvenile  For some, late 2020 brought with it an air of optimism regarding the fate of right-wing populism. In the United Kingdom, Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party faded into obscurity, and the populist right’s GB News experiment

For some, late 2020 brought with it an air of optimism regarding the fate of right-wing populism. In the United Kingdom, Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party faded into obscurity, and the populist right’s GB News experiment