Sarah Bush and Lauren Prather in The Conversation:

Can Americans’ trust in elections be rebuilt?

Can Americans’ trust in elections be rebuilt?

Answering that question is complicated by the country’s decentralized system of election management. Researchers have found that trust can be enhanced when whole countries reform their electoral systems to make them fairer and more transparent. Although American elections are democratic, it is difficult to highlight specific qualities – or implement reforms that would make elections even better – because election administration varies from state to state.

Poll worker training and other measures that make it likely that voters have a positive experience on election day can improve Americans’ trust in their elections. This will likely happen at a local level.

Another way that countries help the public understand election quality is through positive reports from trusted election observers, both domestic and international.

More here.

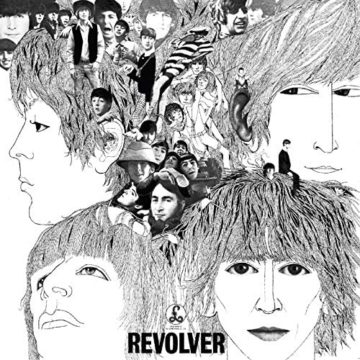

Weber says that most writings about the Beatles can be categorised into one of four principal narratives ‑ four ways of seeing and telling the band’s story. The first and earliest of these is the Fab Four Narrative. This is the more or less official version of the Beatles that evolved following their initial breakthrough. It was propagated by a largely friendly media nudged along by the Beatles themselves, their management and publicists. In the Fab Four Narrative, the Beatles are depicted as four friends whose relationship with each other is easy and free of tension. This is how they come across in their early interviews, their monthly fan magazine, and, especially, in their first two films: A Hard Day’s Night and Help. In Help, for example, the fictionalised Beatles live in a luxurious communal home that is, by mid-sixties standards, high-tech. These are rich young men, leisured and with few responsibilities, but who get along together, well enough to live in the same shared space like perpetual teenagers. As Weber comments, these mainstream films were especially important in differentiating one Beatle from another for a wider public (Jonathan Miller, commenting when they were new on the scene, had thought they all looked the same, like the Midwich Cuckoos).

Weber says that most writings about the Beatles can be categorised into one of four principal narratives ‑ four ways of seeing and telling the band’s story. The first and earliest of these is the Fab Four Narrative. This is the more or less official version of the Beatles that evolved following their initial breakthrough. It was propagated by a largely friendly media nudged along by the Beatles themselves, their management and publicists. In the Fab Four Narrative, the Beatles are depicted as four friends whose relationship with each other is easy and free of tension. This is how they come across in their early interviews, their monthly fan magazine, and, especially, in their first two films: A Hard Day’s Night and Help. In Help, for example, the fictionalised Beatles live in a luxurious communal home that is, by mid-sixties standards, high-tech. These are rich young men, leisured and with few responsibilities, but who get along together, well enough to live in the same shared space like perpetual teenagers. As Weber comments, these mainstream films were especially important in differentiating one Beatle from another for a wider public (Jonathan Miller, commenting when they were new on the scene, had thought they all looked the same, like the Midwich Cuckoos). THE WORD “GENIAL” IN ENGLISH

THE WORD “GENIAL” IN ENGLISH I first read the Book of Revelation in a green pocket-size King James New Testament published by the motel missionaries Gideons International. I was in seventh grade. I remember reading the tiny Bible in the hallway outside my chemistry classroom, in which lurked a boy I loathed named Glenn, who would make fun of my Journey T-shirts. It would be years before I really got into Iron Maiden, but at my friend Jonathan’s house I’d heard Barry Clayton’s creepy recitation of Revelation 13:18 on the title track of The Number of the Beast: “Let him who hath understanding reckon the number of the beast: for it is a human number; its number is six hundred and sixty-six.”

I first read the Book of Revelation in a green pocket-size King James New Testament published by the motel missionaries Gideons International. I was in seventh grade. I remember reading the tiny Bible in the hallway outside my chemistry classroom, in which lurked a boy I loathed named Glenn, who would make fun of my Journey T-shirts. It would be years before I really got into Iron Maiden, but at my friend Jonathan’s house I’d heard Barry Clayton’s creepy recitation of Revelation 13:18 on the title track of The Number of the Beast: “Let him who hath understanding reckon the number of the beast: for it is a human number; its number is six hundred and sixty-six.” Over the years, Marsha Farmer had learned what to look for. As she drove the back roads of rural Alabama, she kept an eye out for dilapidated homes and trailers with wheelchair ramps. Some days, she’d ride the one-car ferry across the river to Lower Peach Tree and other secluded hamlets where a few houses lacked running water and bare soil was visible beneath the floorboards. Other times, she’d scan church prayer lists for the names of families with ailing members.

Over the years, Marsha Farmer had learned what to look for. As she drove the back roads of rural Alabama, she kept an eye out for dilapidated homes and trailers with wheelchair ramps. Some days, she’d ride the one-car ferry across the river to Lower Peach Tree and other secluded hamlets where a few houses lacked running water and bare soil was visible beneath the floorboards. Other times, she’d scan church prayer lists for the names of families with ailing members. After the Internet arrived and flooded the market with new voices, some outlets found that instead of going after the whole audience, it made more financial sense to pick one demographic and dominate it. How? That’s easy. You feed the audience news you know they will like. When Fox had success targeting suburban and rural, mostly white, mostly older conservatives – the late Fox News chief Roger Ailes infamously described his audience as “55 to dead” – other companies soon followed suit.

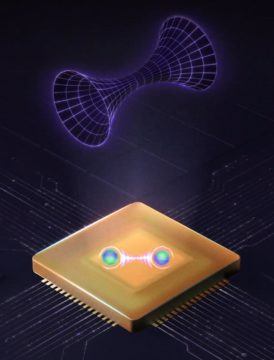

After the Internet arrived and flooded the market with new voices, some outlets found that instead of going after the whole audience, it made more financial sense to pick one demographic and dominate it. How? That’s easy. You feed the audience news you know they will like. When Fox had success targeting suburban and rural, mostly white, mostly older conservatives – the late Fox News chief Roger Ailes infamously described his audience as “55 to dead” – other companies soon followed suit. Physicists have purportedly created the first-ever wormhole, a kind of tunnel theorized in 1935 by Albert Einstein and Nathan Rosen that leads from one place to another by passing into an extra dimension of space.

Physicists have purportedly created the first-ever wormhole, a kind of tunnel theorized in 1935 by Albert Einstein and Nathan Rosen that leads from one place to another by passing into an extra dimension of space. With or without the COVID-19 pandemic, China has maintained a greater capacity to control the internal movement of its population than perhaps any other country in the world. This is primarily enforced through the household registration system (hukou) which has linked the provision of social services to regional locales since 1958. Under Deng Xiaoping, China set about constructing a national labor market, which today allows citizens to enjoy the narrow market freedom to seek employment throughout the country. But social citizenship, including access to state subsidized health care, education, pensions, and housing, is structured at the level of the city.

With or without the COVID-19 pandemic, China has maintained a greater capacity to control the internal movement of its population than perhaps any other country in the world. This is primarily enforced through the household registration system (hukou) which has linked the provision of social services to regional locales since 1958. Under Deng Xiaoping, China set about constructing a national labor market, which today allows citizens to enjoy the narrow market freedom to seek employment throughout the country. But social citizenship, including access to state subsidized health care, education, pensions, and housing, is structured at the level of the city. Man is an

Man is an T

T On a May evening in 1972—eight months after the uprising—Tisdale passed through Attica’s security gates and held his first workshop. He began by asking his students, “What is poetry?” He recorded their answers in his journal: “Personal, deals with emotions, historical, compact (concise), eternal, revolutionary, beauty, rhyme, rhythm, a verbal X-ray of the soul.” Knowing he was under nearly as much scrutiny as the imprisoned men, Tisdale approached the “revolutionary” aspects of poetry with caution. Attica’s administrators feared another revolt. Officers were always present for the workshops; Tisdale’s journal makes special note of the occasions when a Black officer, recruited after the uprising, attended. Regardless of the surveillance, the workshop began to gel after the first few weeks as participants became more comfortable with Tisdale. He noticed quickly that many contributors possessed great skill as poets. They told him that nothing had changed at Attica since the revolt; prison conditions remained abhorrent. They shared an urgency to write about the violence they had witnessed and America’s carceral system in general, and they did not hold back.

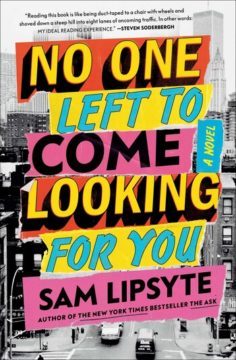

On a May evening in 1972—eight months after the uprising—Tisdale passed through Attica’s security gates and held his first workshop. He began by asking his students, “What is poetry?” He recorded their answers in his journal: “Personal, deals with emotions, historical, compact (concise), eternal, revolutionary, beauty, rhyme, rhythm, a verbal X-ray of the soul.” Knowing he was under nearly as much scrutiny as the imprisoned men, Tisdale approached the “revolutionary” aspects of poetry with caution. Attica’s administrators feared another revolt. Officers were always present for the workshops; Tisdale’s journal makes special note of the occasions when a Black officer, recruited after the uprising, attended. Regardless of the surveillance, the workshop began to gel after the first few weeks as participants became more comfortable with Tisdale. He noticed quickly that many contributors possessed great skill as poets. They told him that nothing had changed at Attica since the revolt; prison conditions remained abhorrent. They shared an urgency to write about the violence they had witnessed and America’s carceral system in general, and they did not hold back. ONE OF SAM LIPSYTE’S SIGNATURE ACCOMPLISHMENTS has been to find the baroque musicality in the emergent vocabularies—commercial, bureaucratic, wellness-industrial, pornographic—opened up by twenty-first-century English. “Hark would shepherd the sermon weirdward,” he writes in his 2019 novel about an entrepreneurial inspirational speaker, “the measured language fracturing, his docile flock of reasonable tips for better corporate living driven off the best practices cliff, the crowd in horrified witness.” Across his first six books, Lipsyte’s sentences have been excessive, pun-laden, and lyrically raunchy. When language threatens to sound measured, a character with a zany name can be counted on to fracture it.

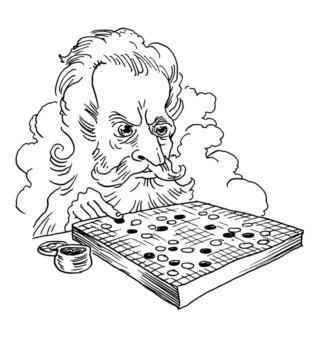

ONE OF SAM LIPSYTE’S SIGNATURE ACCOMPLISHMENTS has been to find the baroque musicality in the emergent vocabularies—commercial, bureaucratic, wellness-industrial, pornographic—opened up by twenty-first-century English. “Hark would shepherd the sermon weirdward,” he writes in his 2019 novel about an entrepreneurial inspirational speaker, “the measured language fracturing, his docile flock of reasonable tips for better corporate living driven off the best practices cliff, the crowd in horrified witness.” Across his first six books, Lipsyte’s sentences have been excessive, pun-laden, and lyrically raunchy. When language threatens to sound measured, a character with a zany name can be counted on to fracture it. Science was supposed to have banished God, but he keeps turning up in our latest technologies. He is the ghost lurking in our data sets, the cockroach hiding beneath the particle accelerator. He briefly appeared three years ago in Seoul, on the sixth floor of the Four Seasons Hotel, where hundreds of people had gathered to watch Lee Sedol, one of the world’s leading go champions, play against AlphaGo, an algorithm created by Google’s DeepMind. Go is an ancient Chinese board game that is exponentially more complex than chess; the number of possible moves exceeds the number of atoms in the universe. Midway through the match, AlphaGo made a move so bizarre that everyone in the room concluded it was a mistake. “It’s not a human move,” said one former champion. “I’ve never seen a human play this move.” Even AlphaGo’s creator could not explain the algorithm’s choice. But it proved decisive. The computer won that game, then the next, claiming victory over Sedol in the best-of-five match.

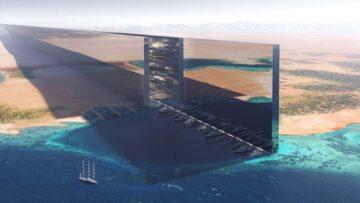

Science was supposed to have banished God, but he keeps turning up in our latest technologies. He is the ghost lurking in our data sets, the cockroach hiding beneath the particle accelerator. He briefly appeared three years ago in Seoul, on the sixth floor of the Four Seasons Hotel, where hundreds of people had gathered to watch Lee Sedol, one of the world’s leading go champions, play against AlphaGo, an algorithm created by Google’s DeepMind. Go is an ancient Chinese board game that is exponentially more complex than chess; the number of possible moves exceeds the number of atoms in the universe. Midway through the match, AlphaGo made a move so bizarre that everyone in the room concluded it was a mistake. “It’s not a human move,” said one former champion. “I’ve never seen a human play this move.” Even AlphaGo’s creator could not explain the algorithm’s choice. But it proved decisive. The computer won that game, then the next, claiming victory over Sedol in the best-of-five match. The future starts now? Drone footage shows construction beginning on Saudi Arabia’s sci-fi megacity called

The future starts now? Drone footage shows construction beginning on Saudi Arabia’s sci-fi megacity called