Category: Recommended Reading

Michael Heizer’s ‘City’: A Visit to a Ruin Being Born

Kirsten Swenson at Art in America:

The trip to Michael Heizer’s City begins in a city: Las Vegas, city of neon and glass, concrete and gravel. I cannot think about City without reference to its nearest desert metropolis, where water and social safety nets are in short supply. Most visitors to City will begin here. But to experience Land art is not simply to show up at a destination. It is a journey, a series of encounters with different landscapes and the systems that operate in and around them.

The trip to Michael Heizer’s City begins in a city: Las Vegas, city of neon and glass, concrete and gravel. I cannot think about City without reference to its nearest desert metropolis, where water and social safety nets are in short supply. Most visitors to City will begin here. But to experience Land art is not simply to show up at a destination. It is a journey, a series of encounters with different landscapes and the systems that operate in and around them.

City has been on my mind since the early 2000s and my first visit to Heizer’s Double Negative (1969) for a Land art seminar I taught at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. To experience that work, a visitor descends into deep notches blasted from a mesa about 60 miles northeast of Las Vegas, passing between ragged sandstone walls to emerge from the cut and take in sweeping views of the Virgin River Valley. Anyone can visit Double Negative, of which Heizer has said, “There is nothing there, yet it is still a sculpture.”

more here.

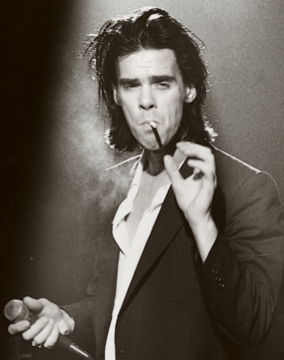

Nick Cave

Kate Mossman and Nick Cave at The New Statesman:

The former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, recently selected Faith, Hope and Carnage as his New Statesman book of the year. I asked him why he found it particularly moving. “There are various familiar ways of putting together the language of faith and the experience of appalling suffering,” he told me. “Some people simply treat faith as consolation: things look terrible but it’s going to turn out fine. Others say that the experience of atrocity negates all possible reference to the sacred or the divine. Nick Cave refuses both sorts of simplicity. For him, the extremity of pain and loss releases something; it pushes you over the edge of whatever limits you had taken for granted and uncovers a kind of imaginative energy, not always welcome.”

The former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, recently selected Faith, Hope and Carnage as his New Statesman book of the year. I asked him why he found it particularly moving. “There are various familiar ways of putting together the language of faith and the experience of appalling suffering,” he told me. “Some people simply treat faith as consolation: things look terrible but it’s going to turn out fine. Others say that the experience of atrocity negates all possible reference to the sacred or the divine. Nick Cave refuses both sorts of simplicity. For him, the extremity of pain and loss releases something; it pushes you over the edge of whatever limits you had taken for granted and uncovers a kind of imaginative energy, not always welcome.”

Cave’s book is perhaps unique in drawing connections between faith, grief and creativity. His God “lives here”, Williams told me, “where the God of the Book of Job or of Elie Wiesel or Dostoevsky lives, not consoling but overwhelming and generating. Not a rationale for suffering or an excuse for looking away but a resource for standing in the middle of it all without complete disintegration of mind and heart.”

more here.

Friday Poem

The Long Boat

When his boat snapped loose

from its mooring, under

the screaking of the gulls,

he tried at first to wave

to his dear ones on shore,

but in the rolling fog

they had already lost their faces.

Too tired even to choose

between jumping and calling,

somehow he felt absolved and free

of his burdens, those mottoes

stamped on his name-tag:

conscience, ambition, and all

that caring.

He was content to lie down

with the family ghosts

in the slop of his cradle,

buffeted by the storm,

endlessly drifting.

Peace! Peace!

To be rocked by the Infinite!

As if it didn’t matter

which way was home;

as if he didn’t know

he loved the earth so much

he wanted to stay forever.

by Stanley Kunitz

from The Collected Poems

World’s Oldest DNA Discovered, Revealing Ancient Arctic Forest Full of Mastodons

Stephanie Pappas in Scientific American:

The oldest DNA ever recovered has revealed a remarkable two-million-year-old ecosystem in Greenland, including the presence of an unlikely explorer: the mastodon.

The oldest DNA ever recovered has revealed a remarkable two-million-year-old ecosystem in Greenland, including the presence of an unlikely explorer: the mastodon.

The DNA, found locked in sediments in a region called Peary Land at the farthest northern reaches of Greenland, shows what life was like in a much warmer period in Earth’s history. The landscape, which is now a harsh polar desert, once hosted trees, caribou and mastodons. Some of the plants and animals that thrived there are now found in Arctic environments, while others are now only found in more temperate boreal forests. “What we see is an ecosystem with no modern analogue,” says Eske Willerslev, an evolutionary geneticist at the University of Cambridge and senior author of the study, which was published in Nature.

Until now, the oldest DNA ever recovered came from a million-year-old mammoth tooth. The oldest DNA ever found in the environment—rather than in a fossil specimen—was also a million years old and came from marine sediments in Antarctica. The newly analyzed ancient DNA comes from a fossil-rich rock formation in Peary Land called Kap København, which preserves sediments from both land and a shallow ocean-side estuary. The formation, which geologists had previously dated to around two million years in age, has already yielded a trove of plant and insect fossils but almost no sign of mammals. The DNA analysis now reveals 102 different genera of plants, including 24 that have never been found fossilized in the formation, and nine animals, including horseshoe crabs, hares, geese and mastodons. That was “mind-blowing,” Willerslev says, because no one thought mastodons ranged that far north.

More here.

T. S. Eliot saw it coming

James Parker in The Atlantic:

Why is april the cruellest month? Why did the chicken cross the road? Why do people watch golf on television? The first question I can answer.

Why is april the cruellest month? Why did the chicken cross the road? Why do people watch golf on television? The first question I can answer.

April is the cruellest month because we are stuck. We’ve stopped dead and we’re going rotten. We are living in the demesne of the crippled king, the Fisher King, where everything sickens and nothing adds up, where the imagination is in shreds, where dark fantasies enthrall us, where men and women are estranged from themselves and one another, and where the cyclical itch of springtime—the spasm in the earth; the sizzling bud; even the gentle, germinal rain—only reminds us how very, very far we are from being reborn. We will not be delivered from this, or not anytime soon. That’s why April is cruel. That’s why April is ironic. That’s why muddy old, sprouty old April, bustling around in her hedgerows, brings us down.

Imagine, if you will, a poem that incorporates the death of Queen Elizabeth II, the blowing up of the Kerch Bridge, Grindr, ketamine, The Purge, Lana Del Rey, the next three COVID variants, and the feeling you get when you can’t remember your Hulu password. Imagine that this poem—which also mysteriously contains all of recorded literature—is written in a form so splintered, so jumpy, but so eerily holistic that it resembles either a new branch of particle physics or a new religion: a new account, at any rate, of the relationships that underpin reality.

More here.

Thursday, December 8, 2022

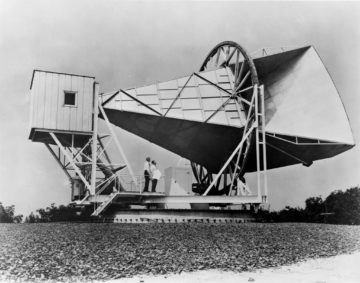

Why cosmology may not end with a bang

David Kordahl in The New Atlantis:

Some sixty years ago, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson were scraping pigeon droppings from a large radio antenna at Bell Labs in New Jersey. They were radio engineers, and their project was straightforward. They wanted to see if they could eliminate the persistent background noise in radio signals, and they supposed that capturing the pigeons roosting in the horn and cleaning it might help. They realized that it didn’t.

Today, the radio noise they detected has been identified as the cosmic microwave background, a subject of intense scientific scrutiny. The pigeon traps have been displayed as relics by the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

More here.

The World The Plague Made: The Black Death And The Rise Of Europe

Leon Vlieger at The Inquisitive Biologist:

The medieval bubonic plague pandemic was a major historical event. But what happened next? To give myself some grounding on this topic, I previously reviewed The Complete History of the Black Death. This provided detailed insights into the spread and mortality caused by the Black Death, which was only the first strike of the Second Plague Pandemic. With that month-long homework exercise in my pocket, I was ready to turn back to the book that send me down this plague-infested rabbit hole in the first place: The World the Plague Made by historian James Belich. One way to characterise this book is that it retells the history of Europe from 1350 onwards as if the plague mattered.

The medieval bubonic plague pandemic was a major historical event. But what happened next? To give myself some grounding on this topic, I previously reviewed The Complete History of the Black Death. This provided detailed insights into the spread and mortality caused by the Black Death, which was only the first strike of the Second Plague Pandemic. With that month-long homework exercise in my pocket, I was ready to turn back to the book that send me down this plague-infested rabbit hole in the first place: The World the Plague Made by historian James Belich. One way to characterise this book is that it retells the history of Europe from 1350 onwards as if the plague mattered.

More here.

Steven Pinker: Enlightenment Now (Last Video of Series)

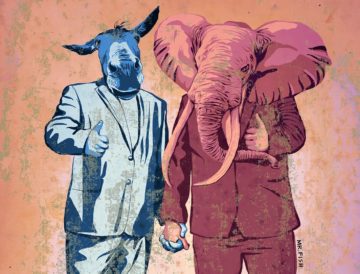

The decades long war waged by the two ruling parties against the working class

Chris Hedges in his Substack newsletter:

The Congressional decision to prohibit railroad workers from going on strike and force them to accept a contract that meets few of their demands is part of the class war that has defined American politics for decades. The two ruling political parties differ only in rhetoric. They are bonded in their determination to reduce wages; dismantle social programs, which the Bill Clinton administration did with welfare; and thwart unions and prohibit strikes, the only tool workers have to pressure employers. This latest move against the railroad unions, where working conditions have descended into a special kind of hell with massive layoffs, the denial of even a single day of paid sick leave, and punishing work schedules that include being forced to “always be on call,” is one more blow to the working class and our anemic democracy.

The Congressional decision to prohibit railroad workers from going on strike and force them to accept a contract that meets few of their demands is part of the class war that has defined American politics for decades. The two ruling political parties differ only in rhetoric. They are bonded in their determination to reduce wages; dismantle social programs, which the Bill Clinton administration did with welfare; and thwart unions and prohibit strikes, the only tool workers have to pressure employers. This latest move against the railroad unions, where working conditions have descended into a special kind of hell with massive layoffs, the denial of even a single day of paid sick leave, and punishing work schedules that include being forced to “always be on call,” is one more blow to the working class and our anemic democracy.

The rage by workers towards the Democratic Party, which once defended their interests, is legitimate, even if, at times, it is expressed by embracing proto-fascists and Donald Trump-like demagogues.

More here.

The Blues Masters

Trompe l’oeil And The Images That Fool The Mind

Caryn James at BBC Culture:

As in magic, viewers of trompe l’oeil know they’re being deceived, and are in on the joke. And there may be something hard-wired in our attraction to those tricks. Gustav Kuhn, Reader in Psychology at Goldsmith’s, University of London, studies cognition and illusions, specifically in magic. No one really knows why we like to be tricked, he says, but he speculates that the attraction comes from “some sort of deep-rooted cognitive mechanism that encourages us to explore the unknown.” Studies of infants point in that direction. “Cognitive conflict is at the essence of magic,” he says. If you hide an object, then reveal the empty space where it was, “For really young infants, they don’t have a concept of object permanency, and so it doesn’t violate their assumptions about the world and they’re not really that interested. However, after the age of about two, where this violates their assumptions, they become captivated.”

As in magic, viewers of trompe l’oeil know they’re being deceived, and are in on the joke. And there may be something hard-wired in our attraction to those tricks. Gustav Kuhn, Reader in Psychology at Goldsmith’s, University of London, studies cognition and illusions, specifically in magic. No one really knows why we like to be tricked, he says, but he speculates that the attraction comes from “some sort of deep-rooted cognitive mechanism that encourages us to explore the unknown.” Studies of infants point in that direction. “Cognitive conflict is at the essence of magic,” he says. If you hide an object, then reveal the empty space where it was, “For really young infants, they don’t have a concept of object permanency, and so it doesn’t violate their assumptions about the world and they’re not really that interested. However, after the age of about two, where this violates their assumptions, they become captivated.”

more here.

Our Age Of Catastrophic Uneventfulness

Nicolas Guilhot at The Point:

The end of history was not an idea that was original to Fukuyama; rather, as befits an age of ideological exhaustion, it was a vintage reissue harking back to an earlier era. The idea was hatched in the rubble of the Second World War and set the tone of intellectual life in the 1950s. Jacques Derrida once reminisced that it was the “daily bread” on which aspiring philosophers were raised back then. Its charismatic impresario was the Russian-born French philosopher Alexandre Kojève. Many others, however, came to terms with the idea the way one does with an ominous prognosis. For the German philosopher Karl Löwith, the end of history was primarily a crisis of meaning and purpose regarding the direction of human existence; for Talmudic scholar and charismatic intellectual Jacob Taubes, it was the exhaustion of eschatological hopes, the last of which were vested in Marxism; for the French philosopher Emmanuel Mounier, the collapse of secular and religious faith; for the theologian Rudolf Bultmann, it meant that the task of finding meaning in human existence had become a purely individual burden; and for the political theorist Judith Shklar, it morphed into an “eschatological consciousness” that “extended from the merely cultural level” to the point where “all mankind is faced with its final hour.”

The end of history was not an idea that was original to Fukuyama; rather, as befits an age of ideological exhaustion, it was a vintage reissue harking back to an earlier era. The idea was hatched in the rubble of the Second World War and set the tone of intellectual life in the 1950s. Jacques Derrida once reminisced that it was the “daily bread” on which aspiring philosophers were raised back then. Its charismatic impresario was the Russian-born French philosopher Alexandre Kojève. Many others, however, came to terms with the idea the way one does with an ominous prognosis. For the German philosopher Karl Löwith, the end of history was primarily a crisis of meaning and purpose regarding the direction of human existence; for Talmudic scholar and charismatic intellectual Jacob Taubes, it was the exhaustion of eschatological hopes, the last of which were vested in Marxism; for the French philosopher Emmanuel Mounier, the collapse of secular and religious faith; for the theologian Rudolf Bultmann, it meant that the task of finding meaning in human existence had become a purely individual burden; and for the political theorist Judith Shklar, it morphed into an “eschatological consciousness” that “extended from the merely cultural level” to the point where “all mankind is faced with its final hour.”

more here.

Thursday Poem

The Secret

Two girls discover

the secret of life

in a sudden line of

poetry.

I who don’t know the

secret wrote

the line. They

told me

(though a third person)

they had found it

but not what it was

not even

what line it was. No doubt

by now, more than a week

later, they have forgotten

the secret,

the line, the name of

the poem. I love them

for not finding what

I can’t find,

and for loving me

for the line I wrote,

and for forgetting it

so that

a thousand times, till death

finds them, they may

discover it again, in other

lines

in other

happenings. And for

wanting to know it,

for

assuming there is

such a secret, yes,

for that

most of all.

by Denise Levertov

from Naked Poetry

The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1969

Papyrus – how books built the world

Kathryn Hughes in The Guardian:

What do you give the queen who has everything? When Mark Antony was wondering how to impress Cleopatra in the run-up to the battle of Actium in 31BC, he knew that jewellery would hardly cut it. The queen of the Ptolemaic kingdom of Egypt had recently dissolved a giant pearl in vinegar and then proceeded to drink it, just because she could. In the face of such exhausted materialism, the Roman general knew that he would have to pull out the stops if he was to win over the woman with whom he was madly in love. So he arrived bearing 200,000 scrolls for the great library at Alexandria. On a logistical level this worked well: since the library was the biggest storehouse of books in the world, Cleopatra almost certainly had the shelf space. As a romantic gesture, it was equally provocative. Within weeks the middle-aged lovers were embarked on the final chapter of their erotic misadventure, the one which would mark the beginning of the end both for them and for Alexandria’s fabled library.

What do you give the queen who has everything? When Mark Antony was wondering how to impress Cleopatra in the run-up to the battle of Actium in 31BC, he knew that jewellery would hardly cut it. The queen of the Ptolemaic kingdom of Egypt had recently dissolved a giant pearl in vinegar and then proceeded to drink it, just because she could. In the face of such exhausted materialism, the Roman general knew that he would have to pull out the stops if he was to win over the woman with whom he was madly in love. So he arrived bearing 200,000 scrolls for the great library at Alexandria. On a logistical level this worked well: since the library was the biggest storehouse of books in the world, Cleopatra almost certainly had the shelf space. As a romantic gesture, it was equally provocative. Within weeks the middle-aged lovers were embarked on the final chapter of their erotic misadventure, the one which would mark the beginning of the end both for them and for Alexandria’s fabled library.

In this generous, sprawling work, the Spanish historian and philologist Irene Vallejo sets out to provide a panoramic survey of how books shaped not just the ancient world but ours too. While she pays due attention to the physicality of the book – what Oxford professor Emma Smith has called its “bookhood” – Vallejo is equally interested in what goes on inside its covers. And also, more importantly, what goes on inside a reader when they take up a volume and embark on an imaginative and intellectual dance that might just change their life. As much as a history of books, Papyrus is also a history of reading.

More here.

In Praise of Parasites?

Jerome Groopman in The New Yorker:

A vacation in the Catskills, one of those beautiful summer days which seem to go on forever, with family friends down at a local pond. I must have been six. I waded around happily, in and out of the tall grasses that grew in the murky water, but when I emerged onto the shore my legs were studded with small black creatures. “Leeches! Don’t touch them!” my mother yelled. I stood terrified. My parents’ friends lit cigarettes and applied the glowing ends to the parasites, which exploded, showering me with blood.

A vacation in the Catskills, one of those beautiful summer days which seem to go on forever, with family friends down at a local pond. I must have been six. I waded around happily, in and out of the tall grasses that grew in the murky water, but when I emerged onto the shore my legs were studded with small black creatures. “Leeches! Don’t touch them!” my mother yelled. I stood terrified. My parents’ friends lit cigarettes and applied the glowing ends to the parasites, which exploded, showering me with blood.

Mom was right, up to a point. If you rip a leech off, you’ll probably leave its jaws behind in the skin, thereby heightening the risk of infection. But her friends’ remedy—back when people smoked, it was practically folk wisdom—isn’t advisable, either. A leech contains, in addition to your blood, plenty of things you don’t want in an open wound. There are ways to safely remove a leech, but almost any source you consult will also make a surprising suggestion: just leave it there. Once the creature has finished making a meal of you—in around twenty minutes—it will drop off, sated. In the meantime, the guest, however unwelcome, is likely doing you no harm. After all, treatment with leeches was a staple of medicine for millennia, and has even been resurgent in recent decades, in applications where the anticoagulant properties of leech saliva are beneficial.

More here.

Wednesday, December 7, 2022

Why Did The Ancient Minoans Worship The Minotaur?

Radical Enhancement, Autonomy, And The Future Of Knowing

Chris Tweedt at Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews:

Technological advances such as Elon Musk’s Neuralink device are meant to be implanted in people’s skulls to interface their brain with powerful computers via the internet. Neuralink’s device will be designed to bring information to subjects’ minds and, possibly, to help subjects acquire skills. If the device works as intended, we will be able to acquire information via a device that is not a natural part of us. Will the acquisition of this information give us knowledge? Will we really know how to do whatever it is that Neuralink’s device assists us in doing? How we answer these questions is important. Knowledge is, arguably, an important human achievement, and if Neuralink’s device (or some other technological assistance) makes it so that we acquire information without knowing, or if it makes it so we do not know how to do what we do as a result of the technological assistance, then we have thereby reduced our ability to succeed in ways important to our humanity. Further, knowledge is arguably required for moral action. Performing a charitable act in full knowledge (and knowing how to perform the act) is more praiseworthy than performing the act in ignorance. If, however, our reliance on new technology diminishes our ability to act knowledgably, then we are less praiseworthy for having relied on that technology.

Technological advances such as Elon Musk’s Neuralink device are meant to be implanted in people’s skulls to interface their brain with powerful computers via the internet. Neuralink’s device will be designed to bring information to subjects’ minds and, possibly, to help subjects acquire skills. If the device works as intended, we will be able to acquire information via a device that is not a natural part of us. Will the acquisition of this information give us knowledge? Will we really know how to do whatever it is that Neuralink’s device assists us in doing? How we answer these questions is important. Knowledge is, arguably, an important human achievement, and if Neuralink’s device (or some other technological assistance) makes it so that we acquire information without knowing, or if it makes it so we do not know how to do what we do as a result of the technological assistance, then we have thereby reduced our ability to succeed in ways important to our humanity. Further, knowledge is arguably required for moral action. Performing a charitable act in full knowledge (and knowing how to perform the act) is more praiseworthy than performing the act in ignorance. If, however, our reliance on new technology diminishes our ability to act knowledgably, then we are less praiseworthy for having relied on that technology.

more here.

The Infrastructure of the Petrochemical Good Life

Justus Nieland at nonsite:

Alden B. Dow is remembered today as a talented architect who adapted Wrightian principles to design modern homes for the midcentury good life, many in his hometown of Midland, Michigan. But Dow was also a prolific amateur filmmaker who ultimately wished to be remembered as a philosopher (fig. 1). Some of his better-known films include two made at Wright’s Taliesin—a black and white film, shot during Dow’s apprenticeship with the master in 1933 and a stunning Kodachrome film of a 1946 trip with his wife to Taliesin West in Arizona, featuring rare footage of Wright himself (fig. 2). These films, which have circulated largely in the service of Wright’s fame as an architect, theorist, and teacher, are just a tiny fraction of the approximately three hundred films produced by Alden Dow from 1923 through the 1960s: travel films and home movies, but also philosophically-oriented experimental films and a host of architectural films. To honor Dow’s legacy and career, some of them are regularly screened today in a small 16mm theater of the architect’s own design in the basement of the Alden B. Dow Home and Studio in Midland, Michigan, as part of that institution’s public outreach and educational mission. Preserved in the archive, the films survive to exemplify the singular creative vision and, yes, philosophy of their maker.

Alden B. Dow is remembered today as a talented architect who adapted Wrightian principles to design modern homes for the midcentury good life, many in his hometown of Midland, Michigan. But Dow was also a prolific amateur filmmaker who ultimately wished to be remembered as a philosopher (fig. 1). Some of his better-known films include two made at Wright’s Taliesin—a black and white film, shot during Dow’s apprenticeship with the master in 1933 and a stunning Kodachrome film of a 1946 trip with his wife to Taliesin West in Arizona, featuring rare footage of Wright himself (fig. 2). These films, which have circulated largely in the service of Wright’s fame as an architect, theorist, and teacher, are just a tiny fraction of the approximately three hundred films produced by Alden Dow from 1923 through the 1960s: travel films and home movies, but also philosophically-oriented experimental films and a host of architectural films. To honor Dow’s legacy and career, some of them are regularly screened today in a small 16mm theater of the architect’s own design in the basement of the Alden B. Dow Home and Studio in Midland, Michigan, as part of that institution’s public outreach and educational mission. Preserved in the archive, the films survive to exemplify the singular creative vision and, yes, philosophy of their maker.

more here.

Wednesday Poem

Atlantis—A Lost Sonnet

How on earth did it happen, I used to wonder

that a whole city—arches, pillars, colonnades,

not to mention vehicles and animals—had all

one fine day gone under?

I mean, I said to myself, the world was small then.

Surely a great city must have been missed?

I miss our old city —

white pepper, white pudding, you and I meeting

under fanlights and low skies to go home in it. Maybe

what really happened is

this: the old fable-makers searched hard for a word

to convey that what is gone is gone forever and

never found it. And so, in the best traditions of

where we come from, they gave their sorrow a name

and drowned it.

by Eavan Boland