Ed Simon in Psyche:

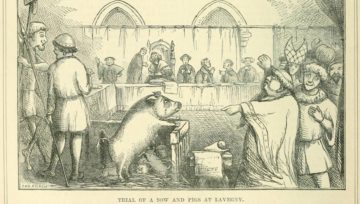

If you were an animal in need of legal representation in early 16th-century Burgundy – a horse that had trampled its owner, a sow that had attacked the farmer’s son, a goat caught in flagrante delicto with the neighbour boy – then the best lawyer in the realm was Barthélemy de Chasseneuz. Though he’d later author the first major text on French customary law, become an eloquent defender of the rights of religious minorities, and be elected parliamentary representative for Dijon, Chasseneuz is most remembered for winning an acquittal on behalf of a group of rats put on trial for eating through the province’s barley crop in 1522. Edward Payson Evans, an American linguist whose book The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals (1906) remains the standard work on the subject, explains that Chasseneuz was ‘forced to employ all sorts of legal shifts and chicane, dilatory pleas and other technical objections,’ including the argument that the rats couldn’t be forced to take the stand because their lives were at risk from the feral cats in the town of Autun, ‘hoping thereby to find some loophole in the meshes of the law through which the accused might escape’ like, well, rats. They were found not guilty.

If you were an animal in need of legal representation in early 16th-century Burgundy – a horse that had trampled its owner, a sow that had attacked the farmer’s son, a goat caught in flagrante delicto with the neighbour boy – then the best lawyer in the realm was Barthélemy de Chasseneuz. Though he’d later author the first major text on French customary law, become an eloquent defender of the rights of religious minorities, and be elected parliamentary representative for Dijon, Chasseneuz is most remembered for winning an acquittal on behalf of a group of rats put on trial for eating through the province’s barley crop in 1522. Edward Payson Evans, an American linguist whose book The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals (1906) remains the standard work on the subject, explains that Chasseneuz was ‘forced to employ all sorts of legal shifts and chicane, dilatory pleas and other technical objections,’ including the argument that the rats couldn’t be forced to take the stand because their lives were at risk from the feral cats in the town of Autun, ‘hoping thereby to find some loophole in the meshes of the law through which the accused might escape’ like, well, rats. They were found not guilty.

Dismissing animal trials as just another backwards practice of a primitive time is to our intellectual detriment, not only because it imposes a pernicious presentism on the past, but also because it’s worth considering whether or not the broader implications of such a ritual don’t have something to tell us about different ways of understanding nonhuman consciousness, and the rights that our fellow creatures deserve.

More here.

If DNA is the code of life, then outfits like GeneArt are printshops — they synthesize custom strands of DNA and ship them to scientists, who can

If DNA is the code of life, then outfits like GeneArt are printshops — they synthesize custom strands of DNA and ship them to scientists, who can  Vivien Sansour is excited about wheat. More than 10,000 years ago, she explains, visionaries in the fertile crescent domesticated it and began to transform it into the croissants, pitas, and baguettes that feed the world today. Sansour studies seeds as a way to “design new things the way that [her] ancestors did.” In 2014 she founded the Heirloom Seed Library and then spent the next four years searching for heirloom varieties for preservation and propagation. Many of these seeds, all indigenous to Palestine, are threatened because of colonial regulation of Palestinian lands and lives. Israel has forced other species onto Palestinian farmers for the sake of efficiency and scale, though it maintains one of the largest heirloom seed libraries at the Arava Institute. While the institute maintains an experimental orchard, the seeds themselves are off-limits to farmers. Sansour insists that while the settler sovereign “took our seeds away from us, they don’t have the story and the system of knowledge associated with the seed.”

Vivien Sansour is excited about wheat. More than 10,000 years ago, she explains, visionaries in the fertile crescent domesticated it and began to transform it into the croissants, pitas, and baguettes that feed the world today. Sansour studies seeds as a way to “design new things the way that [her] ancestors did.” In 2014 she founded the Heirloom Seed Library and then spent the next four years searching for heirloom varieties for preservation and propagation. Many of these seeds, all indigenous to Palestine, are threatened because of colonial regulation of Palestinian lands and lives. Israel has forced other species onto Palestinian farmers for the sake of efficiency and scale, though it maintains one of the largest heirloom seed libraries at the Arava Institute. While the institute maintains an experimental orchard, the seeds themselves are off-limits to farmers. Sansour insists that while the settler sovereign “took our seeds away from us, they don’t have the story and the system of knowledge associated with the seed.” WASHINGTON — I had always been a bah humbug sort of person about Christmas.

WASHINGTON — I had always been a bah humbug sort of person about Christmas. To revisit “The Dick Cavett Show,” which ran late night on ABC from 1969 to 1975 (and in various other incarnations before and after), is to enter a time capsule—not just because of Cavett’s guests, who included aging Hollywood doyennes (Bette Davis, Katharine Hepburn), rock legends in their chaotic prime (Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix), and squabbling intellectuals (Gore Vidal, Norman Mailer), but because Cavett’s free-flowing yet informed interviewing style is all but absent from contemporary television. Late-night shows are now tightly scripted affairs, where celebrities can plug a new movie, tell a rehearsed anecdote, and maybe get roped into a lip-synch battle. But Cavett gently prodded his subjects into revealing themselves. Though he was pegged as the “intellectual” late-night host, he resisted the label. He was a creature of show business: spontaneous, witty, and interested in everything.

To revisit “The Dick Cavett Show,” which ran late night on ABC from 1969 to 1975 (and in various other incarnations before and after), is to enter a time capsule—not just because of Cavett’s guests, who included aging Hollywood doyennes (Bette Davis, Katharine Hepburn), rock legends in their chaotic prime (Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix), and squabbling intellectuals (Gore Vidal, Norman Mailer), but because Cavett’s free-flowing yet informed interviewing style is all but absent from contemporary television. Late-night shows are now tightly scripted affairs, where celebrities can plug a new movie, tell a rehearsed anecdote, and maybe get roped into a lip-synch battle. But Cavett gently prodded his subjects into revealing themselves. Though he was pegged as the “intellectual” late-night host, he resisted the label. He was a creature of show business: spontaneous, witty, and interested in everything. Fleur Jaeggy would like to see herself as something of a mystic.

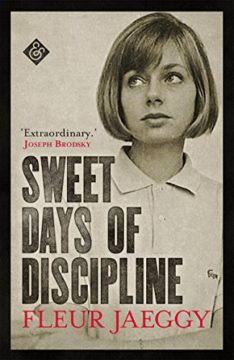

Fleur Jaeggy would like to see herself as something of a mystic. The story behind the story of “The Velveteen Rabbit” is itself a kind of fairy tale. Much of it was revealed to me during an interview I did with Margery’s daughter, Pamela Bianco, in 1979. Pamela, born in London in 1906, was an art prodigy, and by the tender age of 12, was one of the most famous children in the world. She was 62 when I met her and working in relative obscurity, as she had done for much of her adult life. During our lengthy conversation, she described the evolution of “The Velveteen Rabbit” and her crucial part in its inception. Pamela was the most childlike person I have ever met. That may well be because her childhood was taken from her. I have never quite forgotten her.

The story behind the story of “The Velveteen Rabbit” is itself a kind of fairy tale. Much of it was revealed to me during an interview I did with Margery’s daughter, Pamela Bianco, in 1979. Pamela, born in London in 1906, was an art prodigy, and by the tender age of 12, was one of the most famous children in the world. She was 62 when I met her and working in relative obscurity, as she had done for much of her adult life. During our lengthy conversation, she described the evolution of “The Velveteen Rabbit” and her crucial part in its inception. Pamela was the most childlike person I have ever met. That may well be because her childhood was taken from her. I have never quite forgotten her. At twenty-six, at the embarrassing end of a series of attempts at channelling Kerouac, I was beyond broke, back in my home town, living in my aunt and uncle’s basement. Having courted and won a girl I had courted but never come close to winning in high school, I was now losing her via my pathetically dwindling prospects. One night she said, “I’m not saying I’m great or anything, but still I think I deserve better than this.”

At twenty-six, at the embarrassing end of a series of attempts at channelling Kerouac, I was beyond broke, back in my home town, living in my aunt and uncle’s basement. Having courted and won a girl I had courted but never come close to winning in high school, I was now losing her via my pathetically dwindling prospects. One night she said, “I’m not saying I’m great or anything, but still I think I deserve better than this.” Stimulating neurons that are linked to alertness helps rats with cochlear implants learn to quickly recognize tunes, researchers have found. The results suggest that activity in a brain region called the locus coeruleus (LC) improves hearing perception in deaf rodents. Researchers say the insights are important for understanding how the brain processes sound, but caution that the approach is a long way from helping people. “It’s like we gave them a cup of coffee,” says Robert Froemke, an otolaryngologist at New York University School of Medicine and a co-author of the study, published in Nature on 21 December

Stimulating neurons that are linked to alertness helps rats with cochlear implants learn to quickly recognize tunes, researchers have found. The results suggest that activity in a brain region called the locus coeruleus (LC) improves hearing perception in deaf rodents. Researchers say the insights are important for understanding how the brain processes sound, but caution that the approach is a long way from helping people. “It’s like we gave them a cup of coffee,” says Robert Froemke, an otolaryngologist at New York University School of Medicine and a co-author of the study, published in Nature on 21 December With a title like that, obviously I will be making a nitpicky technical point. I’ll start by making the point, then explain why I think it matters.

With a title like that, obviously I will be making a nitpicky technical point. I’ll start by making the point, then explain why I think it matters. The main federal agency guiding America’s pandemic policy is the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, which sets widely adopted policies on masking, vaccination, distancing, and other mitigation efforts to slow the spread of COVID and ensure the virus is less morbid when it leads to infection. The CDC is, in part, a scientific agency—they use facts and principles of science to guide policy—but they are also fundamentally a political agency: The director is appointed by the president of the United States, and the CDC’s guidance often balances public health and welfare with other priorities of the executive branch.

The main federal agency guiding America’s pandemic policy is the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, which sets widely adopted policies on masking, vaccination, distancing, and other mitigation efforts to slow the spread of COVID and ensure the virus is less morbid when it leads to infection. The CDC is, in part, a scientific agency—they use facts and principles of science to guide policy—but they are also fundamentally a political agency: The director is appointed by the president of the United States, and the CDC’s guidance often balances public health and welfare with other priorities of the executive branch. Glass frogs can boost their transparency by up to 61 per cent by storing most of their blood in their liver while they sleep. Researchers hope that understanding how the frogs manage to pool their blood this way without experiencing blood clots could provide new insights into preventing dangerous clots in other animals, including humans.

Glass frogs can boost their transparency by up to 61 per cent by storing most of their blood in their liver while they sleep. Researchers hope that understanding how the frogs manage to pool their blood this way without experiencing blood clots could provide new insights into preventing dangerous clots in other animals, including humans. A novel, which is fiction, can never be classified as nonfiction—indeed, a “nonfiction novel” sounds like a contradiction in terms. This is because when we use these two categories, we are not talking about form or content—as we might with more granular terms, such as autofiction, memoir or biography—but making a judgement call. We are saying: these are the books that tell “the truth”, whereas these are the ones that do not.

A novel, which is fiction, can never be classified as nonfiction—indeed, a “nonfiction novel” sounds like a contradiction in terms. This is because when we use these two categories, we are not talking about form or content—as we might with more granular terms, such as autofiction, memoir or biography—but making a judgement call. We are saying: these are the books that tell “the truth”, whereas these are the ones that do not.