Wendell Steavenson in More Intelligent Life:

On August 11th an unemployed 42-year-old grabbed his shotgun and a large jerry can of petrol. Dressed in a T-shirt and flip-flops, Bassam al-Sheikh Hussein walked into a Beirut branch of the Federal Bank of Lebanon, intending to carry out a heist. As he entered, he slammed the heavy metal gate behind him with all his force. “It sounded like an explosion,” he told me. Inside the bank were seven or eight employees, two male customers and a woman who slumped to the floor at the sight of the armed man, begging to be spared. Hussein stopped her from banging her head and let her leave. “I was not rash,” he told me. “I was very calculated. I was calm.”

On August 11th an unemployed 42-year-old grabbed his shotgun and a large jerry can of petrol. Dressed in a T-shirt and flip-flops, Bassam al-Sheikh Hussein walked into a Beirut branch of the Federal Bank of Lebanon, intending to carry out a heist. As he entered, he slammed the heavy metal gate behind him with all his force. “It sounded like an explosion,” he told me. Inside the bank were seven or eight employees, two male customers and a woman who slumped to the floor at the sight of the armed man, begging to be spared. Hussein stopped her from banging her head and let her leave. “I was not rash,” he told me. “I was very calculated. I was calm.”

He sloshed petrol over the desks and an oily, pungent smell rose up. Employees complained it was suffocating them. Hussein grabbed the manager by the collar of his suit jacket and propelled him into a room at the rear. He jabbed the rifle into his back and told him to open the vault. The bank manager complied.

Inside were tall stacks of Lebanese pounds, as well as a small pile of dollars, amounting to around $3,500. The manager counted out four $100 bills.

“Are you fucking stupid or what?” said Hussein.

The manager offered him all the dollars.

“Call your bosses and tell them I want all of my $210,000 right now!”

More here.

Bushra Rehman’s stunningly beautiful coming-of-age novel “Roses, in the Mouth of a Lion” is set in the Corona neighborhood of Queens, New York, which was enshrined in pop culture by Paul Simon’s 1972 hit “Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard.” Rehman’s exuberant young protagonist, Razia, knows the song well, although it puzzles her. “Why would Paul Simon be singing about Corona?” she muses. “I didn’t see many white people there unless they were policemen or firemen, and I didn’t think Paul Simon had ever been one of those.”

Bushra Rehman’s stunningly beautiful coming-of-age novel “Roses, in the Mouth of a Lion” is set in the Corona neighborhood of Queens, New York, which was enshrined in pop culture by Paul Simon’s 1972 hit “Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard.” Rehman’s exuberant young protagonist, Razia, knows the song well, although it puzzles her. “Why would Paul Simon be singing about Corona?” she muses. “I didn’t see many white people there unless they were policemen or firemen, and I didn’t think Paul Simon had ever been one of those.” I

I Failure, as Costica Bradatan puts it in his bracing new book, is good for you, but not for the reasons you might think. “In Praise of Failure” is maddening, disturbing, exasperating, seductive — I found myself turned around at so many points that even as I was closing in on the last chapter I wasn’t quite sure where I would land at the end.

Failure, as Costica Bradatan puts it in his bracing new book, is good for you, but not for the reasons you might think. “In Praise of Failure” is maddening, disturbing, exasperating, seductive — I found myself turned around at so many points that even as I was closing in on the last chapter I wasn’t quite sure where I would land at the end. You might worry about offending someone, or lack the time to articulate your disagreement. You may even find yourself in a conversational context so polarised that introducing an objection will likely backfire.

You might worry about offending someone, or lack the time to articulate your disagreement. You may even find yourself in a conversational context so polarised that introducing an objection will likely backfire. For years, I resisted

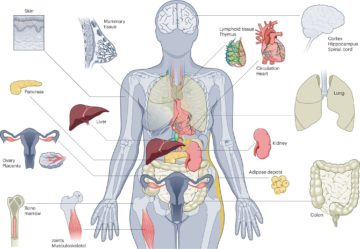

For years, I resisted  Multiple researchers at the Jackson Laboratory (JAX) are taking part in an ambitious research program spanning several top research institutions to study senescent cells. Senescent cells stop dividing in response to stressors and seemingly have a role to play in human health and the aging process. Recent research with mice suggests that clearing senescent cells delays the onset of age-related dysfunction and disease as well as all-cause mortality.

Multiple researchers at the Jackson Laboratory (JAX) are taking part in an ambitious research program spanning several top research institutions to study senescent cells. Senescent cells stop dividing in response to stressors and seemingly have a role to play in human health and the aging process. Recent research with mice suggests that clearing senescent cells delays the onset of age-related dysfunction and disease as well as all-cause mortality. E

E In a quiet group chat in an obscure part of the internet, a small number of anonymous accounts are swapping references from academic publications and feverishly poring over complex graphs of DNA analysis. These are not your average trolls, but scholars, researchers and students who have come together online to discuss the latest findings in archaeology. Why would established academics not be having these conversations in a conference hall or a lecture theatre? The answer might surprise you.

In a quiet group chat in an obscure part of the internet, a small number of anonymous accounts are swapping references from academic publications and feverishly poring over complex graphs of DNA analysis. These are not your average trolls, but scholars, researchers and students who have come together online to discuss the latest findings in archaeology. Why would established academics not be having these conversations in a conference hall or a lecture theatre? The answer might surprise you. I work on AI alignment,

I work on AI alignment,  That we often are not the masters of our own machines, and can even become their witless lackeys, is a cautionary claim as old as the Hebrew prophet Isaiah and as urgent as the latest bogus newsfeed on Dr. Fauci’s evil ways. (Instead of saving lives, he’s been busy, don’t you know, torturing puppies, rendering impotent our patriotic men, and implanting surveillance chips in our brains: accusations all conveyed via apps relentlessly surveilled by Facebook, Apple, Google, and their like.) As a species gifted with inventive minds and opposable thumbs, we are ever about the business of generating new tools and techniques that will, we are certain, better our lives. Time after time, though, those new methods and machines also prove to change our public spaces and private selves in radical ways we fail to foresee and come to regret.

That we often are not the masters of our own machines, and can even become their witless lackeys, is a cautionary claim as old as the Hebrew prophet Isaiah and as urgent as the latest bogus newsfeed on Dr. Fauci’s evil ways. (Instead of saving lives, he’s been busy, don’t you know, torturing puppies, rendering impotent our patriotic men, and implanting surveillance chips in our brains: accusations all conveyed via apps relentlessly surveilled by Facebook, Apple, Google, and their like.) As a species gifted with inventive minds and opposable thumbs, we are ever about the business of generating new tools and techniques that will, we are certain, better our lives. Time after time, though, those new methods and machines also prove to change our public spaces and private selves in radical ways we fail to foresee and come to regret. IN A TEACHING MANUAL she wrote in the 1980s, the artist Sybil Andrews stressed the importance of reaching into an image for its essence, stripping away whatever stagnated it. “Can you catch that? Can you get that sense of movement?” she would ask. The advice revealed a design philosophy that had defined her work for decades: her 1931 linocut In Full Cry shows a row of horses leaping over a hedge, their riders’ coattails soaring behind them. The lines themselves are Andrews’s subject, vigorous and unflinching. “I don’t draw the horse jumping,” she said. “I draw the jump.”

IN A TEACHING MANUAL she wrote in the 1980s, the artist Sybil Andrews stressed the importance of reaching into an image for its essence, stripping away whatever stagnated it. “Can you catch that? Can you get that sense of movement?” she would ask. The advice revealed a design philosophy that had defined her work for decades: her 1931 linocut In Full Cry shows a row of horses leaping over a hedge, their riders’ coattails soaring behind them. The lines themselves are Andrews’s subject, vigorous and unflinching. “I don’t draw the horse jumping,” she said. “I draw the jump.” To write a letter or a postcard meant, relatively speaking, going slow. This was particularly so if one wrote by hand, but true too with a typewriter or word processor and printer. People have always liked to complain about the speed of the mail, but today the once-noble medium has been denigrated to the point of being deemed “snail mail.” Contracts to carry the mail once were prestigious and coveted things and underwrote our evolving national transportation system. The concept of a “post road” dates to colonial times. The Old Boston Post Road, which began as a forest trail in 1673 and eventually became part of US Route 1, is a common reference still in the vernacular of southern New England. Waterways, filling up with mail-carrying canal boats and paddlewheel steamers, were declared post roads in 1823. The Pony Express, though it operated only for eighteen months in 1860 and 1861, quickly entered the mythology of the Old West.

To write a letter or a postcard meant, relatively speaking, going slow. This was particularly so if one wrote by hand, but true too with a typewriter or word processor and printer. People have always liked to complain about the speed of the mail, but today the once-noble medium has been denigrated to the point of being deemed “snail mail.” Contracts to carry the mail once were prestigious and coveted things and underwrote our evolving national transportation system. The concept of a “post road” dates to colonial times. The Old Boston Post Road, which began as a forest trail in 1673 and eventually became part of US Route 1, is a common reference still in the vernacular of southern New England. Waterways, filling up with mail-carrying canal boats and paddlewheel steamers, were declared post roads in 1823. The Pony Express, though it operated only for eighteen months in 1860 and 1861, quickly entered the mythology of the Old West. Before it was an edict, and a death sentence, it was a rumor. To many, it must have seemed improbable; I imagine my grandmother, buying her vegetables at the market, settling her baby on her hip, craning to hear the news—a border, where? Two borders, to be exact. On the eve of their departure, in 1947, after more than three hundred years on the subcontinent, the British sliced the land into a Hindu-majority India flanked by a Muslim-majority West Pakistan and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), a thousand miles apart. The boundaries were drawn up in five weeks by an English barrister who had famously never before been east of Paris; he flew home directly afterward and burned his papers. The slash of his pen is known as Partition.

Before it was an edict, and a death sentence, it was a rumor. To many, it must have seemed improbable; I imagine my grandmother, buying her vegetables at the market, settling her baby on her hip, craning to hear the news—a border, where? Two borders, to be exact. On the eve of their departure, in 1947, after more than three hundred years on the subcontinent, the British sliced the land into a Hindu-majority India flanked by a Muslim-majority West Pakistan and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), a thousand miles apart. The boundaries were drawn up in five weeks by an English barrister who had famously never before been east of Paris; he flew home directly afterward and burned his papers. The slash of his pen is known as Partition.