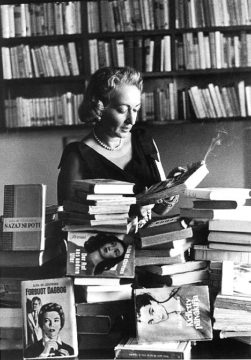

Joumana Khatib at the NYT:

Rome, 1950: The diary begins innocently enough, with the name of its owner, Valeria Cossati, written in a neat script.

Rome, 1950: The diary begins innocently enough, with the name of its owner, Valeria Cossati, written in a neat script.

Valeria is buying cigarettes for her husband when she is entranced by the stacks of gleaming black notebooks at the tobacco shop. She’s not permitted to buy one there on Sundays, she’s told, but the tobacconist gives her one anyway, which she stashes under her coat. She doesn’t yet know there’s a devil hiding in its pages.

This deception begins the Cuban-Italian writer Alba de Céspedes’s novel FORBIDDEN NOTEBOOK (Astra House, 259 pp., $26), first published in 1952. Valeria is married with two adult children; the family is under financial strain, compelling her to work in an office and manage her household without the help of a maid. She has coped with these pressures handsomely, she believes. She is a “transparent” woman, simple, “a person who had no surprises either for myself or for others.”

more here.

When British brain surgeon Henry Marsh sat down beside his patient’s bed following surgery, the bad news he was about to deliver stemmed from his own mistake. The man had a trapped nerve in his arm that required an operation – but after making a midline incision in his neck,

When British brain surgeon Henry Marsh sat down beside his patient’s bed following surgery, the bad news he was about to deliver stemmed from his own mistake. The man had a trapped nerve in his arm that required an operation – but after making a midline incision in his neck,  Animals that produce many offspring tend to have short lives, while less prolific species tend to live longer. Cockroaches lay hundreds of eggs while living less than a year. Mice have dozens of babies during their year or two of life. Humpback whales produce only one calf every two or three years and live for decades. The rule of thumb seems to reflect evolutionary strategies that channel nutritional resources either into reproducing quickly or into growing more robust for a long-term advantage.

Animals that produce many offspring tend to have short lives, while less prolific species tend to live longer. Cockroaches lay hundreds of eggs while living less than a year. Mice have dozens of babies during their year or two of life. Humpback whales produce only one calf every two or three years and live for decades. The rule of thumb seems to reflect evolutionary strategies that channel nutritional resources either into reproducing quickly or into growing more robust for a long-term advantage. A carefully administered and properly controlled dosage of a hallucinogen, their studies attest, can accomplish in a single, not-to-be-repeated session what years of psychotherapy and regimens of antidepressant medications often fail to achieve.

A carefully administered and properly controlled dosage of a hallucinogen, their studies attest, can accomplish in a single, not-to-be-repeated session what years of psychotherapy and regimens of antidepressant medications often fail to achieve. A boyfriend just going through the motions. A spouse worn into the rut of habit. A jetlagged traveler’s message of exhaustion-fraught longing. A suppressed kiss, unwelcome or badly timed. These were some of the interpretations that reverberated in my brain after I viewed a

A boyfriend just going through the motions. A spouse worn into the rut of habit. A jetlagged traveler’s message of exhaustion-fraught longing. A suppressed kiss, unwelcome or badly timed. These were some of the interpretations that reverberated in my brain after I viewed a  Forty years ago the literary theorist Peter Brooks made a name for himself by championing a then-unfashionable argument: we understand ourselves through stories. Narrative, he wrote in his landmark 1984 book Reading for the Plot, is “the principal ordering force” by which we make meaning out of our lives.

Forty years ago the literary theorist Peter Brooks made a name for himself by championing a then-unfashionable argument: we understand ourselves through stories. Narrative, he wrote in his landmark 1984 book Reading for the Plot, is “the principal ordering force” by which we make meaning out of our lives. New year, new variant. Just as scientists were getting to grips with the

New year, new variant. Just as scientists were getting to grips with the  I was the

I was the  It was my daughter Clara’s seventh birthday party, a scene at once familiar and bizarre. The celebration was an American take on a classic script: a shared meal of pizza and picnic food, a few close COVID-compliant friends and family, a beaming kid blowing out candles on a heavily iced cake. With roughly 380,000 boys and girls around the world turning seven each day, it was a ritual no doubt repeated by many, the world’s most prolific primate singing “Happy Birthday” in an unbroken global chorus.

It was my daughter Clara’s seventh birthday party, a scene at once familiar and bizarre. The celebration was an American take on a classic script: a shared meal of pizza and picnic food, a few close COVID-compliant friends and family, a beaming kid blowing out candles on a heavily iced cake. With roughly 380,000 boys and girls around the world turning seven each day, it was a ritual no doubt repeated by many, the world’s most prolific primate singing “Happy Birthday” in an unbroken global chorus. I was nineteen, maybe twenty, when I realized I was empty-headed. I was in a college English class, and we were in a sunny seminar room, discussing “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” or possibly “The Waves.” I raised my hand to say something and suddenly realized that I had no idea what I planned to say. For a moment, I panicked. Then the teacher called on me, I opened my mouth, and words emerged. Where had they come from? Evidently, I’d had a thought—that was why I’d raised my hand. But I hadn’t known what the thought would be until I spoke it. How weird was that?

I was nineteen, maybe twenty, when I realized I was empty-headed. I was in a college English class, and we were in a sunny seminar room, discussing “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” or possibly “The Waves.” I raised my hand to say something and suddenly realized that I had no idea what I planned to say. For a moment, I panicked. Then the teacher called on me, I opened my mouth, and words emerged. Where had they come from? Evidently, I’d had a thought—that was why I’d raised my hand. But I hadn’t known what the thought would be until I spoke it. How weird was that? Last year I spoke to a long list of leading scientists and doctors for a piece I was reporting. Of all the things they shared with me, one quote stood out:

Last year I spoke to a long list of leading scientists and doctors for a piece I was reporting. Of all the things they shared with me, one quote stood out: Some time ago, I fell into conversation with a colleague about what we had been reading lately, and the person suggested that I absolutely must give Henry James’s “The Ambassadors” a try.

Some time ago, I fell into conversation with a colleague about what we had been reading lately, and the person suggested that I absolutely must give Henry James’s “The Ambassadors” a try. The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) has granted a conditional license for a vaccine created by Dalan Animal Health, a US biotech company, to help protect honeybees from American foulbrood disease.

The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) has granted a conditional license for a vaccine created by Dalan Animal Health, a US biotech company, to help protect honeybees from American foulbrood disease. German leaders’ vigorous efforts over the last year to better equip the Bundeswehr—and thus prove their commitment to the security of Europe—have been described as a dramatic turning point in postwar German history. Chancellor Olaf Scholz himself used such language last February to justify his pledge to take out an unprecedented €100 billion loan, which he referred to as a “special fund” for “necessary investments and armament projects.” Unwilling to leave any doubt about his commitment to strengthening the armed forces, Scholz announced that annual defense budget increases would follow. Speaking to parliament three days after the war began, Scholz justified this orgy of defense spending by arguing that the Russian invasion marked a “watershed in the history of our continent.” The claim must be understood in reference to the elephant in the German historical imagination: World War II. “Many of us,” the chancellor

German leaders’ vigorous efforts over the last year to better equip the Bundeswehr—and thus prove their commitment to the security of Europe—have been described as a dramatic turning point in postwar German history. Chancellor Olaf Scholz himself used such language last February to justify his pledge to take out an unprecedented €100 billion loan, which he referred to as a “special fund” for “necessary investments and armament projects.” Unwilling to leave any doubt about his commitment to strengthening the armed forces, Scholz announced that annual defense budget increases would follow. Speaking to parliament three days after the war began, Scholz justified this orgy of defense spending by arguing that the Russian invasion marked a “watershed in the history of our continent.” The claim must be understood in reference to the elephant in the German historical imagination: World War II. “Many of us,” the chancellor