Amanda Petrusich at The New Yorker:

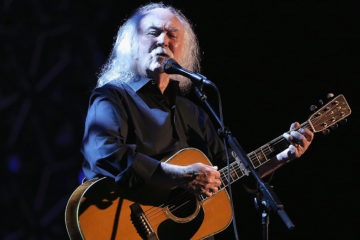

However cantankerous or stubborn Crosby was offstage, when performing, he was seized by a kind of silent joy. You could see it spreading across his face, loosening his features. Music softened him. In his later years, he wore a white mustache, long frizzy hair, and an omnipresent red beanie (knitted by his wife, Jan). He looked like someone who might sell you some garden compost. He looked salty. Performing was the one thing that seemed to reliably animate and excite him.

However cantankerous or stubborn Crosby was offstage, when performing, he was seized by a kind of silent joy. You could see it spreading across his face, loosening his features. Music softened him. In his later years, he wore a white mustache, long frizzy hair, and an omnipresent red beanie (knitted by his wife, Jan). He looked like someone who might sell you some garden compost. He looked salty. Performing was the one thing that seemed to reliably animate and excite him.

One of my favorite of Crosby’s vocal performances is a demo of “Everybody’s Been Burned,” a Byrds song from 1967. The tone is somewhere between Nick Drake in his Warwickshire bedroom and Frank Sinatra on a barstool, sloshing a gin Martini. It’s a generous, humane song, about how terrifying it is to go on after loss:

more here.

I first met Charles Simic in 1994 at a dinner to celebrate the Harvard Review’s special issue dedicated to Simic. I had written an essay for the issue titled “He Who Remembers His Shoes” that focused on several of his poems and so was invited to this dinner and seated next to him. While we were eating, a small black ant started crawling across the white table cloth. Simic became mesmerized by this ant. We both wondered if the ant was going to “make it” to the other side, and then, suddenly, our waiter appeared and swept it up. Simic almost wept. (I later learned that ants were his favorite insect.) What an object lesson it was for me in Simic’s compassion for the smallest creatures, what Czesław Miłosz called “immense particulars.” I stayed in touch with Simic off and on after this night, inviting him to read at the M.F.A. program I cofounded in 2001. Simic declined at first, saying he was “too pooped” after a reading tour in Europe, but then agreed to come in 2005. He read at The Fells, John Hayes’ elegant estate overlooking Lake Sunapee in New Hampshire which New England College rented for the occasion. The indelible image of him with the lake and gardens behind him has stayed with me ever since.

I first met Charles Simic in 1994 at a dinner to celebrate the Harvard Review’s special issue dedicated to Simic. I had written an essay for the issue titled “He Who Remembers His Shoes” that focused on several of his poems and so was invited to this dinner and seated next to him. While we were eating, a small black ant started crawling across the white table cloth. Simic became mesmerized by this ant. We both wondered if the ant was going to “make it” to the other side, and then, suddenly, our waiter appeared and swept it up. Simic almost wept. (I later learned that ants were his favorite insect.) What an object lesson it was for me in Simic’s compassion for the smallest creatures, what Czesław Miłosz called “immense particulars.” I stayed in touch with Simic off and on after this night, inviting him to read at the M.F.A. program I cofounded in 2001. Simic declined at first, saying he was “too pooped” after a reading tour in Europe, but then agreed to come in 2005. He read at The Fells, John Hayes’ elegant estate overlooking Lake Sunapee in New Hampshire which New England College rented for the occasion. The indelible image of him with the lake and gardens behind him has stayed with me ever since. So you have some information — how are you going to share it with and present it to the rest of the world? There has been a long history of organizing and displaying information without putting too much thought into it, but Edward Tufte has done an enormous amount to change that. Beginning with

So you have some information — how are you going to share it with and present it to the rest of the world? There has been a long history of organizing and displaying information without putting too much thought into it, but Edward Tufte has done an enormous amount to change that. Beginning with  Being professionally heterodox has probably made it easier to make a name for myself, but it comes with its own set of hangups. There’s a tendency to sort anyone who steps outside of the usual partisan lines into the same bucket, despite the fact that defying orthodoxy should theoretically not consign you to any particular opinion at all. Typically, this pigeonholing is the work of people who are very much orthodox something, usually orthodox liberal Democrats – they’ll claim that anyone who is not exactly what they are is therefore necessarily the opposite of what they are, which is usually a conservative Republican. This is how you get people claiming that Matt Taibbi is a “far-right” journalist. (To add another layer to this onion, by saying that Taibbi is not a far-right journalist, in the eyes of some I have just marked myself as far-right myself.) This dynamic also exists on the right; the conservative Christian David French is frequently called a liberal by his many enemies on the right. None of this is particularly surprising. The orthodox tend to think only in terms of dueling orthodoxies, and if they’re sure you’re not a Yook, you must be a Zook. So it goes.

Being professionally heterodox has probably made it easier to make a name for myself, but it comes with its own set of hangups. There’s a tendency to sort anyone who steps outside of the usual partisan lines into the same bucket, despite the fact that defying orthodoxy should theoretically not consign you to any particular opinion at all. Typically, this pigeonholing is the work of people who are very much orthodox something, usually orthodox liberal Democrats – they’ll claim that anyone who is not exactly what they are is therefore necessarily the opposite of what they are, which is usually a conservative Republican. This is how you get people claiming that Matt Taibbi is a “far-right” journalist. (To add another layer to this onion, by saying that Taibbi is not a far-right journalist, in the eyes of some I have just marked myself as far-right myself.) This dynamic also exists on the right; the conservative Christian David French is frequently called a liberal by his many enemies on the right. None of this is particularly surprising. The orthodox tend to think only in terms of dueling orthodoxies, and if they’re sure you’re not a Yook, you must be a Zook. So it goes. Along, long time ago, some Indians were running along a trail that led to an Indian settlement. As they ran, a rabbit jumped from the bushes and sat before them.

Along, long time ago, some Indians were running along a trail that led to an Indian settlement. As they ran, a rabbit jumped from the bushes and sat before them. The future belongs to those who prepare for it, as scientists who petition federal agencies like NASA and the Department of Energy for research funds know all too well. The price of big-ticket instruments like a space telescope or particle accelerator can be as high as $10 billion.

The future belongs to those who prepare for it, as scientists who petition federal agencies like NASA and the Department of Energy for research funds know all too well. The price of big-ticket instruments like a space telescope or particle accelerator can be as high as $10 billion. Certainly, Ferber’s approach—critical but forgiving to individual people and America at large—stems largely from who she was as a person and the way in which she moved through the world as a feme sole. A firsthand expert on the old maid lifestyle herself, Ferber was never known to have had a romantic or sexual relationship. But far from being a sad, sere figure whom life was passing by, she was vibrant, indefatigable, witty, and successful, a member of the Algonquin Round Table in New York and a winner of the Pulitzer Prize in 1925 for So Big, another wonderful Chicago novel. She saw that book eventually adapted into one silent picture and two talkies. Her 1926 novel Show Boat was made into the famous 1927 musical, and Cimarron (1930), Giant (1952), and The Ice Palace (1958) were all adapted into films as well. When

Certainly, Ferber’s approach—critical but forgiving to individual people and America at large—stems largely from who she was as a person and the way in which she moved through the world as a feme sole. A firsthand expert on the old maid lifestyle herself, Ferber was never known to have had a romantic or sexual relationship. But far from being a sad, sere figure whom life was passing by, she was vibrant, indefatigable, witty, and successful, a member of the Algonquin Round Table in New York and a winner of the Pulitzer Prize in 1925 for So Big, another wonderful Chicago novel. She saw that book eventually adapted into one silent picture and two talkies. Her 1926 novel Show Boat was made into the famous 1927 musical, and Cimarron (1930), Giant (1952), and The Ice Palace (1958) were all adapted into films as well. When  IF A SINGLE QUESTION is guiding for our understanding of Manet’s art during the first half of the 1860s, it is this: What are we to make of the numerous references in his paintings of those years to the work of the great painters of the past? A few of Manet’s historically aware contemporaries recognized explicit references to past art in some of his important pictures of that period; and by the time he died his admirers tended to play down the paintings of the first half of the sixties, if not of the entire decade, largely because of what had come to seem their overall dependence on the Old Masters. By 1912 Blanche could claim, in a kind of hyperbole, that it was impossible to find two paintings in Manet’s oeuvre that had not been inspired by other paintings, old or modern. But it has been chiefly since the retrospective exhibition of 1932 that historians investigating the sources of Manet’s art have come to realize concretely the extent to which it is based upon specific paintings, engravings after paintings, and original prints by artists who preceded him. It is now clear, for example, that most of the important pictures of the sixties depend either wholly or in part on works by Velasquez, Goya, Rubens, Van Dyck, Raphael, Titian, Giorgione, Veronese, Le Nain, Watteau, Chardin, Courbet . . . This by itself is an extraordinary fact, one that must be accounted for if Manet’s enterprise is to be made intelligible.

IF A SINGLE QUESTION is guiding for our understanding of Manet’s art during the first half of the 1860s, it is this: What are we to make of the numerous references in his paintings of those years to the work of the great painters of the past? A few of Manet’s historically aware contemporaries recognized explicit references to past art in some of his important pictures of that period; and by the time he died his admirers tended to play down the paintings of the first half of the sixties, if not of the entire decade, largely because of what had come to seem their overall dependence on the Old Masters. By 1912 Blanche could claim, in a kind of hyperbole, that it was impossible to find two paintings in Manet’s oeuvre that had not been inspired by other paintings, old or modern. But it has been chiefly since the retrospective exhibition of 1932 that historians investigating the sources of Manet’s art have come to realize concretely the extent to which it is based upon specific paintings, engravings after paintings, and original prints by artists who preceded him. It is now clear, for example, that most of the important pictures of the sixties depend either wholly or in part on works by Velasquez, Goya, Rubens, Van Dyck, Raphael, Titian, Giorgione, Veronese, Le Nain, Watteau, Chardin, Courbet . . . This by itself is an extraordinary fact, one that must be accounted for if Manet’s enterprise is to be made intelligible. Indeed, the

Indeed, the  The blue, fin, bowhead, gray, humpback, right and sperm whales are the largest animals alive today. In fact, the blue whale is the largest-known creature ever on Earth, topping even the biggest of the dinosaurs.

The blue, fin, bowhead, gray, humpback, right and sperm whales are the largest animals alive today. In fact, the blue whale is the largest-known creature ever on Earth, topping even the biggest of the dinosaurs. In late 1968, the train and bus stations of Chinese cities filled with sobbing adolescents and frightened parents. The authorities had decreed that teenagers – deployed by

In late 1968, the train and bus stations of Chinese cities filled with sobbing adolescents and frightened parents. The authorities had decreed that teenagers – deployed by  If the coconut symbolizes the natural bounty of the tropical zone in many people’s minds, it is often used to “explain” the human poverty frequently found in the zone. A common assumption in rich countries is that poor countries are poor because their people do not work hard. And given that most, if not all, poor countries are in the tropics, they often attribute the lack of work ethic of the people in poor countries to the easy living that they supposedly get thanks to the bounty of the tropics. In the tropics, it is said, food grows everywhere (bananas, coconuts, mangoes—the usual imagery goes), while the high temperature means that people don’t need sturdy shelter or much clothing.

If the coconut symbolizes the natural bounty of the tropical zone in many people’s minds, it is often used to “explain” the human poverty frequently found in the zone. A common assumption in rich countries is that poor countries are poor because their people do not work hard. And given that most, if not all, poor countries are in the tropics, they often attribute the lack of work ethic of the people in poor countries to the easy living that they supposedly get thanks to the bounty of the tropics. In the tropics, it is said, food grows everywhere (bananas, coconuts, mangoes—the usual imagery goes), while the high temperature means that people don’t need sturdy shelter or much clothing.

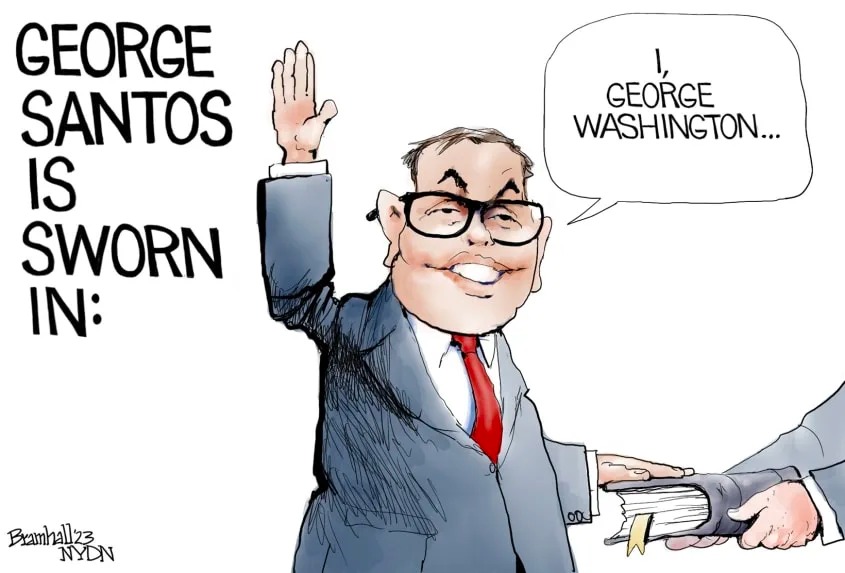

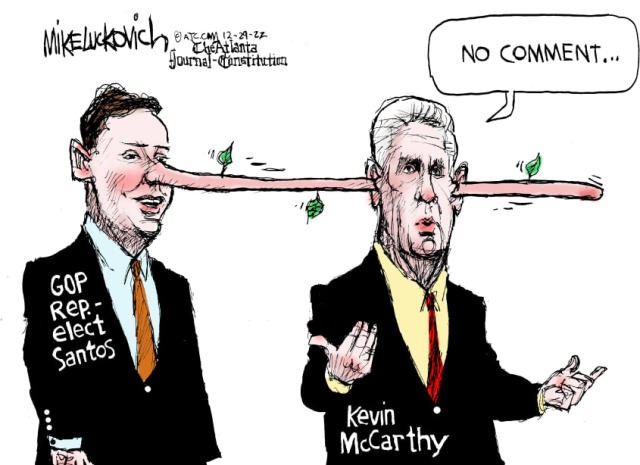

WASHINGTON — It’s not a pretty sight when pols lose power. They wilt, they crumple, they cling to the vestiges, they mourn their vanished entourage and perks. How can their day in the sun be over? One minute they’re running the world and the next, they’re in the room where it doesn’t happen.

WASHINGTON — It’s not a pretty sight when pols lose power. They wilt, they crumple, they cling to the vestiges, they mourn their vanished entourage and perks. How can their day in the sun be over? One minute they’re running the world and the next, they’re in the room where it doesn’t happen. Paul Dicken in LA Review of Books:

Paul Dicken in LA Review of Books: