Dean W. Ball at Hyperdimensional:

Imagine that you are a cook, and you just made a cake in your kitchen. You’ve made a delicious cake, and you’d like to start a business making 1,000 of them a day. So you replicate your kitchen 1,000 times over—you buy 1,000 residential ovens, 1,000 standard mixing bowls, 1,000 bags of flour. And you hire 1,000 humans to follow your recipe, each making their own cake in the various kitchens you’ve built.

Imagine that you are a cook, and you just made a cake in your kitchen. You’ve made a delicious cake, and you’d like to start a business making 1,000 of them a day. So you replicate your kitchen 1,000 times over—you buy 1,000 residential ovens, 1,000 standard mixing bowls, 1,000 bags of flour. And you hire 1,000 humans to follow your recipe, each making their own cake in the various kitchens you’ve built.

Of course no one would do this. And yet this is not that far off from how we today “scale science,” and in some ways we are even less efficient.

What you should do instead, obviously, is build a factory with the ability to make 1,000 cakes at the same time. This was, at one point, a new type of institution that entailed distinct organizational structures (the modern corporation, for example), new relationships of workers to firm owners, novel patterns of work, and much else. The factory enabled and necessitated new technology: in our example, industrial ovens, wholesale purchase of ingredients, and the like, in quantities that would be alien in a residential kitchen. Similarly, it required new occupations that do not map cleanly to their pre-industrial analogs (consider the “chef” or “baker,” for example, versus the “batter-vat cleaner”).

Standing in a pre-industrial residential kitchen, it would be difficult to imagine a factory, partially because there are numerous complementary innovations a factory requires (for example, the ability to manufacture and power industrial-scale cooking equipment), and partially because imagination is hard.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

With their bladed paws, wielded by a rippling mass of pure muscle, sharp eyes, agile reflexes, and crushing fanged jaws, lions are certainly not a predator most animals have any interest in messing with. Especially seeing as they also have the smarts to hunt in packs.

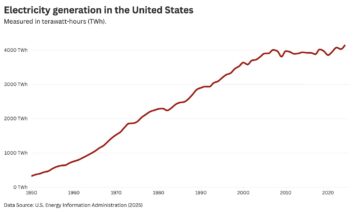

With their bladed paws, wielded by a rippling mass of pure muscle, sharp eyes, agile reflexes, and crushing fanged jaws, lions are certainly not a predator most animals have any interest in messing with. Especially seeing as they also have the smarts to hunt in packs. I often hear about “skyrocketing” demand for electricity in countries like the United States (here’s

I often hear about “skyrocketing” demand for electricity in countries like the United States (here’s

First came the

First came the  A

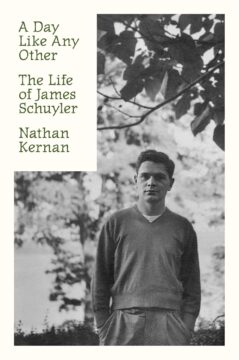

A A MAN LOOKS OVER A FENCE, SPYING. He notes the arrival of a Buick hardtop convertible. Parked now, the driver rolls the top down, using a new automatic mechanism, exposing the interior leather to the elements right at the wrong moment. The camera at first shows a magnificent three, who spill out as from a clown car: Jane Freilicher, Frank O’Hara, and John Ashbery. Then it lands on Jimmy Schuyler in the back, who, doubling as a porter, carries the luggage.

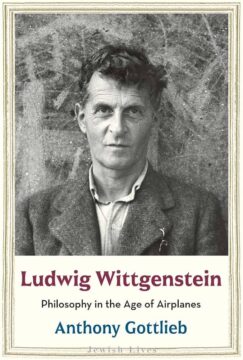

A MAN LOOKS OVER A FENCE, SPYING. He notes the arrival of a Buick hardtop convertible. Parked now, the driver rolls the top down, using a new automatic mechanism, exposing the interior leather to the elements right at the wrong moment. The camera at first shows a magnificent three, who spill out as from a clown car: Jane Freilicher, Frank O’Hara, and John Ashbery. Then it lands on Jimmy Schuyler in the back, who, doubling as a porter, carries the luggage. In 1931, at the age of forty-one, Ludwig Wittgenstein mused in his diary that perhaps his name would live on only as the end point of Western philosophy—“like the name of the one who burnt down the library of Alexandria.” There probably was no such an arsonist. The books of ancient Alexandria seem to have perished mainly by rot and neglect, not in a single blaze.

In 1931, at the age of forty-one, Ludwig Wittgenstein mused in his diary that perhaps his name would live on only as the end point of Western philosophy—“like the name of the one who burnt down the library of Alexandria.” There probably was no such an arsonist. The books of ancient Alexandria seem to have perished mainly by rot and neglect, not in a single blaze. Social Text still exists.

Social Text still exists. The four most advanced AI systems are

The four most advanced AI systems are

A

A Beatriz Ychussie’s career in mathematics seemed to be going really well. She worked at Roskilde University in Denmark where, in 2015 and 2016 alone, she published four papers on mathematical formulae for quantum particles, heat flow and geometry, and reviewed multiple manuscripts for reputable journals. But a few years later, her run of promising studies dried up. An investigation by the publisher of three of those papers found not only that the work was flawed, but that Ychussie didn’t even exist.

Beatriz Ychussie’s career in mathematics seemed to be going really well. She worked at Roskilde University in Denmark where, in 2015 and 2016 alone, she published four papers on mathematical formulae for quantum particles, heat flow and geometry, and reviewed multiple manuscripts for reputable journals. But a few years later, her run of promising studies dried up. An investigation by the publisher of three of those papers found not only that the work was flawed, but that Ychussie didn’t even exist.