Julien Crockett and Alan Lightman at the LARB:

When did you begin on the project of reconciling a scientific worldview with human experience?

When did you begin on the project of reconciling a scientific worldview with human experience?

Probably as a child. It started with my sort of schizophrenic interests in both the sciences and the arts. I did experiments and built rockets. I wrote poetry in which I expressed my awe of the world, my bafflement, my questions.

In one of your earlier books, The Accidental Universe, you write that theoretical physics is “the deepest and purest branch of science. It is the outpost of science closest to philosophy, and religion.” Did you become a theoretical physicist because it allowed you to maintain these dual interests?

Yes, I think so. Of course, in college, I took a lot of courses, and not just science courses. But when it came time to choose a particular science that I wanted to put most of my effort into, it was theoretical physics for the reasons you mentioned. Also, I was attracted by the fact that physics is the most fundamental of all the sciences. I like to dig into the world as deeply as possible.

more here.

Black actresses have always faced barriers. Initially, they were not allowed to be on screen at all. Then, they could only play certain types of roles: typically either as a servant and/or enslaved woman, or as an “exotic” temptress. Never a character that was fully realized, one with depth or nuance.

Black actresses have always faced barriers. Initially, they were not allowed to be on screen at all. Then, they could only play certain types of roles: typically either as a servant and/or enslaved woman, or as an “exotic” temptress. Never a character that was fully realized, one with depth or nuance. There is an astonishing moment near the beginning of

There is an astonishing moment near the beginning of  Stunning as it may sound, nearly half of Americans ages 20 years and up – or more than 122 million people – have high blood pressure, according to a

Stunning as it may sound, nearly half of Americans ages 20 years and up – or more than 122 million people – have high blood pressure, according to a  Although proponents of secret science like to focus on examples in which it has benefited society, insiders from the very beginning of the Cold War worried that the best minds would not be drawn to work that they could not even talk about. Secrecy protected those involved from embarrassment or criminal prosecution, but it also made it much harder to vet experimental protocols, validate the results, or replicate them in follow-up research.

Although proponents of secret science like to focus on examples in which it has benefited society, insiders from the very beginning of the Cold War worried that the best minds would not be drawn to work that they could not even talk about. Secrecy protected those involved from embarrassment or criminal prosecution, but it also made it much harder to vet experimental protocols, validate the results, or replicate them in follow-up research. The crossroads shows up in three separate places in Plato’s accounts of the afterlife. In the Gorgias, Plato describes a “Meadow at the Crossroads,” where one path goes to the Isles of the Blessed, while the other leads to a prison of punishment and retribution.

The crossroads shows up in three separate places in Plato’s accounts of the afterlife. In the Gorgias, Plato describes a “Meadow at the Crossroads,” where one path goes to the Isles of the Blessed, while the other leads to a prison of punishment and retribution. Months after buying the house, I learned, piece-meal, from people who should have told me what they knew about that house before I signed the mortgage papers, that the sprawling white elephant I’d acquired had functioned in the middle past as a transient home for orphans and abandoned children awaiting adoption into foster care. A few years later, the house became an overflow domestic abuse shelter for women hiding from stalking husbands and boyfriends. There were even indications, in two of the basement areas, that meetings of some disreputable fraternal organization, something along the lines of Storm Front, had been held there for a while. These may also have featured a karaoke night, since besides the crumpled confederate flags and vague neo-Nazi debris scattered in corners, there was also a truncated proscenium stage with a microphone stand and a dead amplifier on it.

Months after buying the house, I learned, piece-meal, from people who should have told me what they knew about that house before I signed the mortgage papers, that the sprawling white elephant I’d acquired had functioned in the middle past as a transient home for orphans and abandoned children awaiting adoption into foster care. A few years later, the house became an overflow domestic abuse shelter for women hiding from stalking husbands and boyfriends. There were even indications, in two of the basement areas, that meetings of some disreputable fraternal organization, something along the lines of Storm Front, had been held there for a while. These may also have featured a karaoke night, since besides the crumpled confederate flags and vague neo-Nazi debris scattered in corners, there was also a truncated proscenium stage with a microphone stand and a dead amplifier on it. Hundreds of scientists around the world are looking for ways to treat heart attacks. But few started where Hedva Haykin has: in the brain. Haykin, a doctoral student at the Technion — Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa, wants to know whether stimulating a region of the brain involved in positive emotion and motivation can influence how the heart heals.

Hundreds of scientists around the world are looking for ways to treat heart attacks. But few started where Hedva Haykin has: in the brain. Haykin, a doctoral student at the Technion — Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa, wants to know whether stimulating a region of the brain involved in positive emotion and motivation can influence how the heart heals. You’ve probably heard of the famous Trolley case. Here is one version: suppose a runaway trolley is about to hit five workers who, by accident, happen to be working on the track. The only way to prevent their death is by pushing a switch that will redirect the trolley onto another track. Unfortunately, there is another worker on this sidetrack who will be killed if the switch is pushed. The question: Is it permissible to push the switch, saving five people but killing one?

You’ve probably heard of the famous Trolley case. Here is one version: suppose a runaway trolley is about to hit five workers who, by accident, happen to be working on the track. The only way to prevent their death is by pushing a switch that will redirect the trolley onto another track. Unfortunately, there is another worker on this sidetrack who will be killed if the switch is pushed. The question: Is it permissible to push the switch, saving five people but killing one? What a week we just had! Each morning brought fresh examples of unexpected sassy, moody, passive-aggressive behavior from “Sydney,” the internal codename for the new chat mode of Microsoft Bing, which is powered by GPT. For those who’ve been in a cave, the highlights include: Sydney

What a week we just had! Each morning brought fresh examples of unexpected sassy, moody, passive-aggressive behavior from “Sydney,” the internal codename for the new chat mode of Microsoft Bing, which is powered by GPT. For those who’ve been in a cave, the highlights include: Sydney  In America, so the myth goes, freedom favors the bold and ambitious individual. From Benjamin Franklin to Steve Jobs, our national mythology has lionized and celebrated bright, plucky, self-motivated characters who work hard to realize innovative ideas. Though born and raised in families, communities, and other collectives, the story goes, these singular personalities rise above the crowd, buoyed by the protected freedoms and rights that American laws have conferred and intent on filling the public space with their own ballooning potential. Those who succeed do so of their own volition, and those who fail prove themselves simply incapable. America is, in other words, the world’s only true meritocracy.

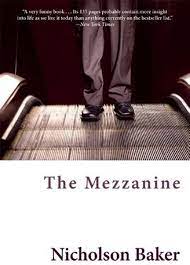

In America, so the myth goes, freedom favors the bold and ambitious individual. From Benjamin Franklin to Steve Jobs, our national mythology has lionized and celebrated bright, plucky, self-motivated characters who work hard to realize innovative ideas. Though born and raised in families, communities, and other collectives, the story goes, these singular personalities rise above the crowd, buoyed by the protected freedoms and rights that American laws have conferred and intent on filling the public space with their own ballooning potential. Those who succeed do so of their own volition, and those who fail prove themselves simply incapable. America is, in other words, the world’s only true meritocracy. To read Baker is to be infected by the desire to put every experience, however small, into words that describe it precisely. Having read a short stack of his novels by way of preparation for this review, I found myself considering pieces of refuse on the street with ferocious care. Grocery receipt, I thought, looking at a white scrap on the sidewalk, small purchase. Small store, too: you can tell from the purple ink. Big supermarkets use black ink nowadays. And so on, to the point where I had to turn off the tiny Nicholson Baker in my head, repeatedly, lest my attention be utterly absorbed by the world around me, leaving me paralyzed in the middle of a crosswalk. That’s one thing you can say about Baker: More than almost anyone writing today, he makes you look.

To read Baker is to be infected by the desire to put every experience, however small, into words that describe it precisely. Having read a short stack of his novels by way of preparation for this review, I found myself considering pieces of refuse on the street with ferocious care. Grocery receipt, I thought, looking at a white scrap on the sidewalk, small purchase. Small store, too: you can tell from the purple ink. Big supermarkets use black ink nowadays. And so on, to the point where I had to turn off the tiny Nicholson Baker in my head, repeatedly, lest my attention be utterly absorbed by the world around me, leaving me paralyzed in the middle of a crosswalk. That’s one thing you can say about Baker: More than almost anyone writing today, he makes you look.