At Banagher

Then all of a sudden there appears to me

The journeyman tailor who was my antecedent:

Up on a table, cross-legged, ripping out

A garment he must recut or resew,

His lips tight back, a thread between his teeth,

Keeping his counsel always, giving none,

His eyelids steady as wrinkled horn or iron.

Self-absenting, both migrant and ensconced;

Admitted into kitchens, into clothes

His touch has the power to turn to cloth again—

All of a sudden he appears to me,

Unopen, unmendacious, unillumined.

………………………………… *

So more power to him on the job there, ill at ease

Under my scrutiny in spite of years

Of being inscrutable as he threaded needles

Or matched the facings, linings, hems and seams.

He holds the needle just off center, squinting,

And licks the thread and licks and sweeps it through,

Then takes his time to draw both threads out even,

Plucking them sharply twice. Then back to stitching.

Does he ever question what it all amounts to?

Or ever will? Or care where he lays his head?

My Lord Buddha of Banagher, the way

Is opener for you being in it.

by Seamus Heaney

from The Spirit Level

UNTIL THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

UNTIL THE NINETEENTH CENTURY The map of Balanchine’s life once he left Russia in 1924 and until he finally settled into the New York City Ballet in 1948 may read as a kind of wandering, but his life as an artist was made of circles: the revolving of the repertory, the return to old ballets, the rethinking and recalibration of steps and phrases. To the dismay of his audience, for instance, Balanchine pared back the iconic

The map of Balanchine’s life once he left Russia in 1924 and until he finally settled into the New York City Ballet in 1948 may read as a kind of wandering, but his life as an artist was made of circles: the revolving of the repertory, the return to old ballets, the rethinking and recalibration of steps and phrases. To the dismay of his audience, for instance, Balanchine pared back the iconic  One afternoon a few weeks ago, Alicea Hotchkiss’s 14-year-old son, Eli, came home from his high school in Tampa with a question about something a classmate had said to him. He’d heard the student use the word “gay” as an insult, so Eli responded the way he always does when this happens. “Hey,” Eli said, “my dad’s gay.” But this time, Eli told his mom, the other kid offered a startling rebuke: You’re not allowed to say that at school.

One afternoon a few weeks ago, Alicea Hotchkiss’s 14-year-old son, Eli, came home from his high school in Tampa with a question about something a classmate had said to him. He’d heard the student use the word “gay” as an insult, so Eli responded the way he always does when this happens. “Hey,” Eli said, “my dad’s gay.” But this time, Eli told his mom, the other kid offered a startling rebuke: You’re not allowed to say that at school. I was never into house plants until I bought one on a whim—a prayer plant, it was called, a lush, leafy thing with painterly green spots and ribs of bright red veins. The night I brought it home I heard a rustling in my room. Had something scurried? A mouse? Three jumpy nights passed before I realized what was happening: The plant was moving. During the day, its leaves would splay flat, sunbathing, but at night they’d clamber over one another to stand at attention, their stems steadily rising as the leaves turned vertical, like hands in prayer.

I was never into house plants until I bought one on a whim—a prayer plant, it was called, a lush, leafy thing with painterly green spots and ribs of bright red veins. The night I brought it home I heard a rustling in my room. Had something scurried? A mouse? Three jumpy nights passed before I realized what was happening: The plant was moving. During the day, its leaves would splay flat, sunbathing, but at night they’d clamber over one another to stand at attention, their stems steadily rising as the leaves turned vertical, like hands in prayer. The Polish poet Adam Zagajewski’s great poem “To Go to Lvov” has a special importance for many young poets in different languages. That poem weaves the historical and the personal, the rhythms of cataclysm and of ordinary life, loss and persistence, all embodied in Zagajewski’s native city. “To Go to Lvov” has provided a model — intensely local, adamantly not nationalistic — for poems rooted in Philadelphia, Buenos Aires and Lahore.

The Polish poet Adam Zagajewski’s great poem “To Go to Lvov” has a special importance for many young poets in different languages. That poem weaves the historical and the personal, the rhythms of cataclysm and of ordinary life, loss and persistence, all embodied in Zagajewski’s native city. “To Go to Lvov” has provided a model — intensely local, adamantly not nationalistic — for poems rooted in Philadelphia, Buenos Aires and Lahore.

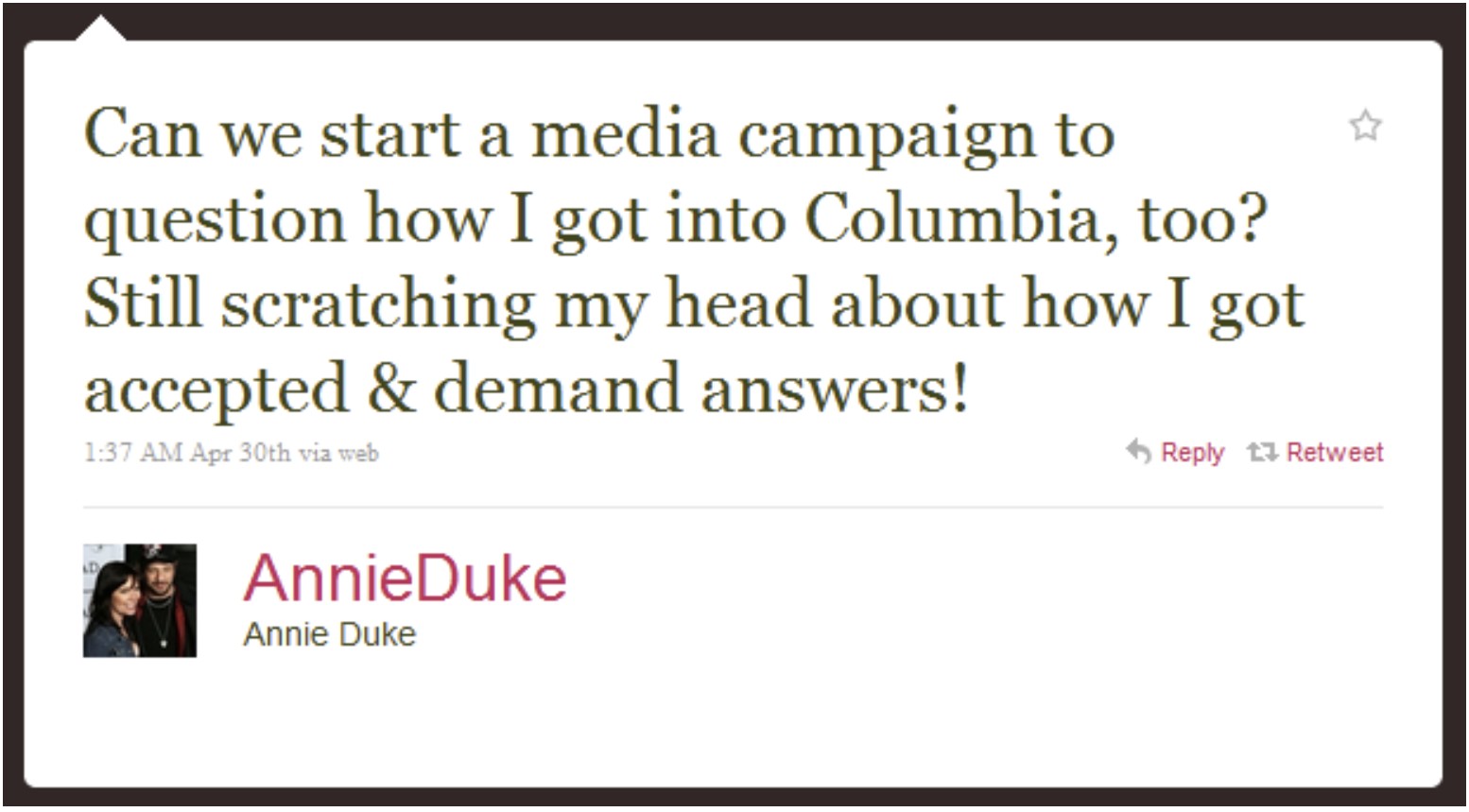

Human behavior is often paradoxical. We show humility to prove we’re better than other people, we bravely defy social norms so that people will praise us, and we donate to charity anonymously to get credit for not caring about getting credit. Here, I argue that these and other social paradoxes have a common thread: they are all attempts to signal a trait while concealing the fact that one is signaling the trait. Such self-negating signals emerge from the interaction of two cognitive abilities: 1) cue-based inference, and 2) recursive mentalizing. If agents can model each other’s mental states, including their intentions to signal positive traits, then intentional signals of positive traits can, themselves, become cues of negative traits. The result is that status-seeking and virtue-signaling are forced to occur covertly, without becoming common knowledge among signalers or recipients. Social paradoxes also play a crucial role in enabling intergroup dominance by inhibiting common knowledge of the group’s dominance-seeking tactics, which would otherwise disrupt coordination by eliciting moral disapproval. The analysis of social paradoxes can explain a variety of puzzling aspects of human social life, including the cultural evolution of status symbols, the function of sacred values, and the nature of political belief systems.

Human behavior is often paradoxical. We show humility to prove we’re better than other people, we bravely defy social norms so that people will praise us, and we donate to charity anonymously to get credit for not caring about getting credit. Here, I argue that these and other social paradoxes have a common thread: they are all attempts to signal a trait while concealing the fact that one is signaling the trait. Such self-negating signals emerge from the interaction of two cognitive abilities: 1) cue-based inference, and 2) recursive mentalizing. If agents can model each other’s mental states, including their intentions to signal positive traits, then intentional signals of positive traits can, themselves, become cues of negative traits. The result is that status-seeking and virtue-signaling are forced to occur covertly, without becoming common knowledge among signalers or recipients. Social paradoxes also play a crucial role in enabling intergroup dominance by inhibiting common knowledge of the group’s dominance-seeking tactics, which would otherwise disrupt coordination by eliciting moral disapproval. The analysis of social paradoxes can explain a variety of puzzling aspects of human social life, including the cultural evolution of status symbols, the function of sacred values, and the nature of political belief systems. The large masterpieces in the upper two rooms mushroom into psychological and spatial multitudes. Constant is working at the scale of the Mexican muralists while echoing something of Chris Ofili’s early dazzling dotted paintings with elephant dung attached. You look at Constant’s work all at once and also millimeter by millimeter, bead by bead. The maniacal density of visual information is transporting.

The large masterpieces in the upper two rooms mushroom into psychological and spatial multitudes. Constant is working at the scale of the Mexican muralists while echoing something of Chris Ofili’s early dazzling dotted paintings with elephant dung attached. You look at Constant’s work all at once and also millimeter by millimeter, bead by bead. The maniacal density of visual information is transporting. As a scholar, I decided to bring my devotion to BTS to my research. Because of my growing fascination with this segment of BTS fandom and their love for the group, I interviewed 25 Gen-X women of diverse backgrounds who currently reside in the United States. Older women face enormous stigma for loving a “boy band,” and the seven Korean men of BTS are wholly different from the men many of us were taught to idealize. Women my age are rarely given the space to express desire, let alone lust, and I wanted to understand the contours and contexts of their experience.

As a scholar, I decided to bring my devotion to BTS to my research. Because of my growing fascination with this segment of BTS fandom and their love for the group, I interviewed 25 Gen-X women of diverse backgrounds who currently reside in the United States. Older women face enormous stigma for loving a “boy band,” and the seven Korean men of BTS are wholly different from the men many of us were taught to idealize. Women my age are rarely given the space to express desire, let alone lust, and I wanted to understand the contours and contexts of their experience. A

A It didn’t take long for Microsoft’s

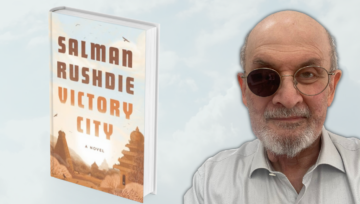

It didn’t take long for Microsoft’s  Salman Rushdie found his voice in 1975. His first novel, Grimus, published earlier that year, had been ignored by the public and derided by the critics. At the same time, Rushdie was watching younger contemporaries such as Ian McEwan and Martin Amis cement their places among the British literary elite, while he remained saddled with his day job as an advertising copywriter.

Salman Rushdie found his voice in 1975. His first novel, Grimus, published earlier that year, had been ignored by the public and derided by the critics. At the same time, Rushdie was watching younger contemporaries such as Ian McEwan and Martin Amis cement their places among the British literary elite, while he remained saddled with his day job as an advertising copywriter. Given the new reality, and my full acknowledgment of the new reality, and my refusal to go down with the sinking ship of “AI will probably never do X and please stop being so impressed that it just did X”—many have wondered, why aren’t I much more terrified? Why am I still not fully on board with the Orthodox AI doom scenario, the Eliezer Yudkowsky one, the one where an unaligned AI will sooner or later (probably sooner) unleash self-replicating nanobots that turn us all to goo?

Given the new reality, and my full acknowledgment of the new reality, and my refusal to go down with the sinking ship of “AI will probably never do X and please stop being so impressed that it just did X”—many have wondered, why aren’t I much more terrified? Why am I still not fully on board with the Orthodox AI doom scenario, the Eliezer Yudkowsky one, the one where an unaligned AI will sooner or later (probably sooner) unleash self-replicating nanobots that turn us all to goo? Speculation encompasses a duality at the core of all financial activity. When pushed to its outermost limit, it can unleash formidable destructive forces and lead to the burst of market bubbles, such as seventeenth-century Amsterdam’s notorious tulip craze, the Victorian era’s railway manias, last century’s Great Depression, or the more recent 2008 global financial crisis. During these periods, market “passions” take hold: traders venerate ethereal values with no material referents or links to “fundamentals.” Yet speculation is also the market’s indispensable lubricant. All speculative trades calibrate risks to generate yields and prevent markets from “overheating.”

Speculation encompasses a duality at the core of all financial activity. When pushed to its outermost limit, it can unleash formidable destructive forces and lead to the burst of market bubbles, such as seventeenth-century Amsterdam’s notorious tulip craze, the Victorian era’s railway manias, last century’s Great Depression, or the more recent 2008 global financial crisis. During these periods, market “passions” take hold: traders venerate ethereal values with no material referents or links to “fundamentals.” Yet speculation is also the market’s indispensable lubricant. All speculative trades calibrate risks to generate yields and prevent markets from “overheating.”