Michael Marshall in Nature:

From hot springs to DNA forensics

In the summer of 1966, while he was an undergraduate at Indiana University, Hudson Freeze went to live in a cabin on the edge of Yellowstone National Park. He was working for microbiologist Thomas Brock, who was convinced that certain microorganisms were living at surprisingly high temperatures. Dodging bears, and the traffic jams they caused, Freeze visited the hot springs every day to sample their bacteria. On 19 September, Freeze succeeded in growing a sample of yellowish microbes from Mushroom Spring. Under a microscope, he found an array of cells collected from the near-boiling fluids. “I was seeing something that nobody had ever seen before,” says Freeze, now at the Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute in La Jolla, California. “I still get goosebumps when I remember looking into the microscope.”

In the summer of 1966, while he was an undergraduate at Indiana University, Hudson Freeze went to live in a cabin on the edge of Yellowstone National Park. He was working for microbiologist Thomas Brock, who was convinced that certain microorganisms were living at surprisingly high temperatures. Dodging bears, and the traffic jams they caused, Freeze visited the hot springs every day to sample their bacteria. On 19 September, Freeze succeeded in growing a sample of yellowish microbes from Mushroom Spring. Under a microscope, he found an array of cells collected from the near-boiling fluids. “I was seeing something that nobody had ever seen before,” says Freeze, now at the Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute in La Jolla, California. “I still get goosebumps when I remember looking into the microscope.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

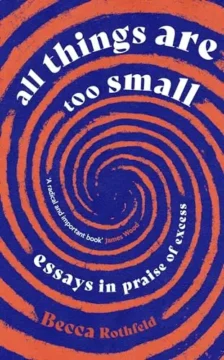

A writer explores the semiotic. All artists work with signs and meanings. For me, writing is a form of semiotic sabotage. It is full of bold advances and strategic retreats, and above all it is shot through with deliberate acts of obstructionism.

A writer explores the semiotic. All artists work with signs and meanings. For me, writing is a form of semiotic sabotage. It is full of bold advances and strategic retreats, and above all it is shot through with deliberate acts of obstructionism. Why are people wrong all the time, anyway? Is it because we human beings are too good at being irrational, using our biases and motivated reasoning to convince ourselves of something that isn’t quite accurate? Or is it something different — unmotivated reasoning, or “unthinkingness,” an unwillingness to do the cognitive work that most of us are actually up to if we try? Gordon Pennycook wants to argue for the latter, and this simple shift has important consequences, including for strategies for getting people to be less susceptible to misinformation and conspiracies.

Why are people wrong all the time, anyway? Is it because we human beings are too good at being irrational, using our biases and motivated reasoning to convince ourselves of something that isn’t quite accurate? Or is it something different — unmotivated reasoning, or “unthinkingness,” an unwillingness to do the cognitive work that most of us are actually up to if we try? Gordon Pennycook wants to argue for the latter, and this simple shift has important consequences, including for strategies for getting people to be less susceptible to misinformation and conspiracies. In most superhero stories, the villains are so deranged or evil that they operate outside the boundaries of society. “SuperKitties” and its ilk focus on characters who do bad things from within the boundaries of society: Their actions are hurtful or wrong, but they were committed because the character believed they were reasonable or permitted. Children may get more out of this type of character because this is exactly the kind of conflict they experience with parents, siblings and classmates; it is even a situation they may find themselves in, having done something that seemed fun or helpful only to receive a scolding, warning or lecture in response.

In most superhero stories, the villains are so deranged or evil that they operate outside the boundaries of society. “SuperKitties” and its ilk focus on characters who do bad things from within the boundaries of society: Their actions are hurtful or wrong, but they were committed because the character believed they were reasonable or permitted. Children may get more out of this type of character because this is exactly the kind of conflict they experience with parents, siblings and classmates; it is even a situation they may find themselves in, having done something that seemed fun or helpful only to receive a scolding, warning or lecture in response. When Robert Hooke gazed through his microscope at a slice of cork and coined the term ‘cell’ in 1665, he was really looking at just the walls of the dead cells. The squishy contents typically found within would become objects of ongoing study. But for many plant scientists, the walls themselves faded into the background. They were considered passive containers for the exciting biology inside.

When Robert Hooke gazed through his microscope at a slice of cork and coined the term ‘cell’ in 1665, he was really looking at just the walls of the dead cells. The squishy contents typically found within would become objects of ongoing study. But for many plant scientists, the walls themselves faded into the background. They were considered passive containers for the exciting biology inside. How do we know when others know what we know? Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker’s latest book, When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows, delves into how ‘common knowledge’ can cement or explode social relations. Common knowledge — awareness of mutual understanding — can explain the

How do we know when others know what we know? Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker’s latest book, When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows, delves into how ‘common knowledge’ can cement or explode social relations. Common knowledge — awareness of mutual understanding — can explain the  G

G Each time I take a long trip, I lose at least one scarf or hat, sometimes even a pair of sunglasses or a watch. I’ve also lost a number of things when moving house: a piece of moulding from an old rustic wardrobe, a few blinds, and once I even lost the typewriter I used to write my first works. Although the hotel rooms I left were small, and the apartments I left were clearly empty, the things were still missing later; somehow, somewhere, they had disappeared in the no man’s land between departure and arrival, it happened so regularly that I began to expect it when packing my suitcase or my boxes, as if it were a sacrifice, a price I had to pay for the change in my circumstances, and in that respect, despite all the randomness, it was still appropriate. However, in the course of my everyday life, the number of things around me never decreased, but rather increased, the piles grew higher, the folders thicker, I could imagine that a fire would break out and I would tuck my diaries, letters, and photo albums under my arm and run out of the house, but fortunately no fire broke out.

Each time I take a long trip, I lose at least one scarf or hat, sometimes even a pair of sunglasses or a watch. I’ve also lost a number of things when moving house: a piece of moulding from an old rustic wardrobe, a few blinds, and once I even lost the typewriter I used to write my first works. Although the hotel rooms I left were small, and the apartments I left were clearly empty, the things were still missing later; somehow, somewhere, they had disappeared in the no man’s land between departure and arrival, it happened so regularly that I began to expect it when packing my suitcase or my boxes, as if it were a sacrifice, a price I had to pay for the change in my circumstances, and in that respect, despite all the randomness, it was still appropriate. However, in the course of my everyday life, the number of things around me never decreased, but rather increased, the piles grew higher, the folders thicker, I could imagine that a fire would break out and I would tuck my diaries, letters, and photo albums under my arm and run out of the house, but fortunately no fire broke out. Whether I like it or not, the first line of my obituary will probably be that I was the founding editor of

Whether I like it or not, the first line of my obituary will probably be that I was the founding editor of  “The classic example of a hijack is masturbation,” Edward Slingerland tells me. We’re talking about all the evolutionary quirks that humans tend to exploit — the cases where we’re “built” for one purpose, but decide to put that structure to other uses. And masturbation is a classic example.

“The classic example of a hijack is masturbation,” Edward Slingerland tells me. We’re talking about all the evolutionary quirks that humans tend to exploit — the cases where we’re “built” for one purpose, but decide to put that structure to other uses. And masturbation is a classic example. In its first three days, users of a new app from OpenAI deployed artificial intelligence to create strikingly realistic videos of ballot fraud, immigration arrests, protests, crimes and attacks on city streets — none of which took place.

In its first three days, users of a new app from OpenAI deployed artificial intelligence to create strikingly realistic videos of ballot fraud, immigration arrests, protests, crimes and attacks on city streets — none of which took place. Complaints about the state of criticism are a very old story. But nothing I’ve read—from indictments published decades ago by Cyril Connolly, Elizabeth Hardwick, Clement Greenberg, and Gore Vidal to James Wolcott’s evisceration of cultural coverage at The New York Times in a recent issue of Liberties—can top Ian McKellen’s howl for what we’ve lost, telegraphed through every twist and turn of his performance as the curmudgeonly theater critic Jimmy Erskine in The Critic (2023).

Complaints about the state of criticism are a very old story. But nothing I’ve read—from indictments published decades ago by Cyril Connolly, Elizabeth Hardwick, Clement Greenberg, and Gore Vidal to James Wolcott’s evisceration of cultural coverage at The New York Times in a recent issue of Liberties—can top Ian McKellen’s howl for what we’ve lost, telegraphed through every twist and turn of his performance as the curmudgeonly theater critic Jimmy Erskine in The Critic (2023).