Clare Watson in The Scientist:

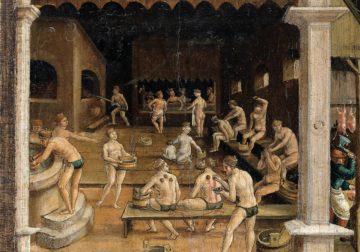

In medieval times, long before there were bathrooms in private homes, bathing was a social affair. Visitors to Dutch and German bathhouses in the late Middle Ages emerged from such spaces cleansed of more than just their grime: They also received basic medical care from “baders,” bathhouse proprietors who were also licensed health practitioners, skilled at lancing abscesses and pulling teeth. Steam rooms, mineral baths, cupping, and herbal concoctions were also commonly used to alleviate ailments from scabies and leprosy to migraines and miscarriages.

In medieval times, long before there were bathrooms in private homes, bathing was a social affair. Visitors to Dutch and German bathhouses in the late Middle Ages emerged from such spaces cleansed of more than just their grime: They also received basic medical care from “baders,” bathhouse proprietors who were also licensed health practitioners, skilled at lancing abscesses and pulling teeth. Steam rooms, mineral baths, cupping, and herbal concoctions were also commonly used to alleviate ailments from scabies and leprosy to migraines and miscarriages.

Not until Victorian times would bathhouses become a little noticed but influential item in public health policies. But according to Janna Coomans, a historian at Utrecht University in the Netherlands who studies public health in medieval cities, bathhouses provided access to more affordable medical care as baders charged less than doctors for their services. Sweating, bloodletting, and lancing were attempts to correct an imbalance in the four “humors”—phlegm, blood, yellow bile and black bile—that were thought to cause ill health. While these practices may seem unhygienic by modern standards, bathhouses enabled “a large part of the population to maintain health and hygienic norms, according to their ideas of health,” Coomans says.

More here.

Around noon on March 9, I learned that the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) had shut down the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), where my company has some of its accounts. My co-founder and I were in the middle of a call with some of our advisors, all experienced hands in the tech startup world actively advising and investing in tech startups like ours. The Zoom room was empty within seconds. We all immediately knew what that meant: The cash we pay our employees and vendors was now locked up—perhaps indefinitely.

Around noon on March 9, I learned that the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) had shut down the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), where my company has some of its accounts. My co-founder and I were in the middle of a call with some of our advisors, all experienced hands in the tech startup world actively advising and investing in tech startups like ours. The Zoom room was empty within seconds. We all immediately knew what that meant: The cash we pay our employees and vendors was now locked up—perhaps indefinitely. On Sunday, February 5, Olof Sisask and Thomas Bloom received an email containing a stunning breakthrough on the biggest unsolved problem in their field. Zander Kelley, a graduate student at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, had sent Sisask and Bloom

On Sunday, February 5, Olof Sisask and Thomas Bloom received an email containing a stunning breakthrough on the biggest unsolved problem in their field. Zander Kelley, a graduate student at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, had sent Sisask and Bloom  Dante Alighieri’s

Dante Alighieri’s  As

As  F

F Seven years ago, during the Republican Presidential primary, Donald Trump appeared onstage at Dordt University, a Christian institution in Iowa, and made a confession of faith. “I’m a true believer,” he said, and he conducted an impromptu poll. “Is everybody a true believer, in this room?” He was scarcely the first Presidential candidate to make a religious appeal, but he might have been the first one to address Christian voters so explicitly as a special interest. “You have the strongest lobby ever,” he said. “But I never hear about a ‘Christian lobby.’ ” He made his audience a promise. “If I’m there, you’re going to have plenty of power,” he said. “You’re going to have somebody representing you very, very well.”

Seven years ago, during the Republican Presidential primary, Donald Trump appeared onstage at Dordt University, a Christian institution in Iowa, and made a confession of faith. “I’m a true believer,” he said, and he conducted an impromptu poll. “Is everybody a true believer, in this room?” He was scarcely the first Presidential candidate to make a religious appeal, but he might have been the first one to address Christian voters so explicitly as a special interest. “You have the strongest lobby ever,” he said. “But I never hear about a ‘Christian lobby.’ ” He made his audience a promise. “If I’m there, you’re going to have plenty of power,” he said. “You’re going to have somebody representing you very, very well.” Researchers have hijacked a molecular ‘syringe’ that some viruses and bacteria use to infect their hosts, and put it to work

Researchers have hijacked a molecular ‘syringe’ that some viruses and bacteria use to infect their hosts, and put it to work  My bathroom is ugly. My bathroom is so ugly that when I tell people my bathroom is ugly and they say it can’t be that ugly I always like to show it to them. Then they come into my bathroom and they are like, Holy shit. This bathroom is so ugly. And I say, I know, I told you.

My bathroom is ugly. My bathroom is so ugly that when I tell people my bathroom is ugly and they say it can’t be that ugly I always like to show it to them. Then they come into my bathroom and they are like, Holy shit. This bathroom is so ugly. And I say, I know, I told you. To my eye, the clock looked like a ruin. Frostbitten shards of its face lay about in the weeds. In places, northerly winds had worn the gilt ornamentation around the dial’s circumference to a sandy, amorphous mass. Everywhere, paint flaked. Mold grew on a slender lip above the lower numerals. At around fourteen feet high, the clock was only just accommodated on the side of the old barn. Brickwork was visible beneath the whitewash at the center of its face. The clock’s movement had stopped months before my arrival, but the downward-dragging force of ruination continued to act on the clock’s hands, pulling them from five-after to half-past three. There, the hands had finally seized. All else moved on: vines crept over the top of the barn and down the north face of the pitched terracotta; weeds grew seven or eight feet tall; cracks ran in the walls of the barn.

To my eye, the clock looked like a ruin. Frostbitten shards of its face lay about in the weeds. In places, northerly winds had worn the gilt ornamentation around the dial’s circumference to a sandy, amorphous mass. Everywhere, paint flaked. Mold grew on a slender lip above the lower numerals. At around fourteen feet high, the clock was only just accommodated on the side of the old barn. Brickwork was visible beneath the whitewash at the center of its face. The clock’s movement had stopped months before my arrival, but the downward-dragging force of ruination continued to act on the clock’s hands, pulling them from five-after to half-past three. There, the hands had finally seized. All else moved on: vines crept over the top of the barn and down the north face of the pitched terracotta; weeds grew seven or eight feet tall; cracks ran in the walls of the barn. In the early fifth century BC, the Olympic boxer Kleomedes was disqualified from a match after killing his opponent with a foul move. Outraged at being deprived of the victory and its attendant prize, he became “mad with grief” and tore down a school in his hometown, killing many of the children who were studying there. Kleomedes managed to escape the angry mob that soon pursued him, and disappeared without trace. When the community sought answers from the oracle at Delphi, they were told that Kleomedes was now a hero, and should be honored accordingly with sacrifices. This the people did, and continued to do for centuries to come.

In the early fifth century BC, the Olympic boxer Kleomedes was disqualified from a match after killing his opponent with a foul move. Outraged at being deprived of the victory and its attendant prize, he became “mad with grief” and tore down a school in his hometown, killing many of the children who were studying there. Kleomedes managed to escape the angry mob that soon pursued him, and disappeared without trace. When the community sought answers from the oracle at Delphi, they were told that Kleomedes was now a hero, and should be honored accordingly with sacrifices. This the people did, and continued to do for centuries to come. A unique form of brain stimulation appears to boost people’s ability to remember new information—by mimicking the way our brains create memories.

A unique form of brain stimulation appears to boost people’s ability to remember new information—by mimicking the way our brains create memories. In 1961, the Jaguar E-type sports car (called the XKE in the United States), designed by Malcolm Sayer, premiered at a major auto show in Geneva Switzerland. Enzo Ferrari declared it to be the most beautiful car ever made. Ferrari himself is, of course, a legendary figure in the history of car design. Ferrari’s judgment was thus stunning in a certain respect. It is very common for cars to be put into stereotypical national, cultural, or ethnic categories. So, for example, there are sleek Italian sports cars, elegant but staid British sedans, and powerful American “muscle” cars. Ferrari’s assessment unsettled these standard categories. This was an Italian expert heaping praise on the beauty of a British car.

In 1961, the Jaguar E-type sports car (called the XKE in the United States), designed by Malcolm Sayer, premiered at a major auto show in Geneva Switzerland. Enzo Ferrari declared it to be the most beautiful car ever made. Ferrari himself is, of course, a legendary figure in the history of car design. Ferrari’s judgment was thus stunning in a certain respect. It is very common for cars to be put into stereotypical national, cultural, or ethnic categories. So, for example, there are sleek Italian sports cars, elegant but staid British sedans, and powerful American “muscle” cars. Ferrari’s assessment unsettled these standard categories. This was an Italian expert heaping praise on the beauty of a British car. A

A The incessant hype over AI tools like ChatGPT is inspiring lots of bad opinions from people who have no idea what they’re talking about. From a New York Times columnist

The incessant hype over AI tools like ChatGPT is inspiring lots of bad opinions from people who have no idea what they’re talking about. From a New York Times columnist