Chris Stokel-Walker in New Scientist:

The race to roll out artificial intelligence is happening as quickly as the race to contain it – as two key moments this week demonstrate.

The race to roll out artificial intelligence is happening as quickly as the race to contain it – as two key moments this week demonstrate.

On 10 May, Google announced plans to deploy new large language models, which use machine learning techniques to generate text, across its existing products. “We are reimagining all of our core products, including search,” said Sundar Pichai, the CEO of Google’s parent company Alphabet, at a press conference. The move is widely seen as a response to Microsoft adding similar functionality to its search engine, Bing.

A day later, politicians in the European Union agreed on new rules dictating how and when AI can be used. The bloc’s AI Act has been years in the making, but has moved quickly to stay up to date: in the past month, legislators drafted and passed rules dictating the use of generative AIs, the popularity of which has exploded in the past six months.

More here.

A friend of mine used to joke that women writers discovered friendship in 2015, when the last volume of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet came out. I laughed, but I knew what he meant. It is easy to think of men who navigated the literary world together: Jonson and Shakespeare, Wordsworth and Coleridge, Johnson and Boswell, Shelley and Byron, Marx and Engels, Sartre and Camus, Bellow and Roth, Hughes and Heaney, Amis and Barnes. In Weimar for a day in summer 2014, bitter laughter rose in me when I emerged into Theaterplatz to find a monument to literary bro-dom: Goethe and Schiller in bronze, each with a hand on a shared crown of laurels. With stout folds in Goethe’s breeches and pupils missing from Schiller’s eyes, the unlovely statue had been cast in 1857, twenty-five years after Goethe died, and had stood for more than a century facing the stage where Goethe had directed many of Schiller’s plays. In the early twentieth century, copies of the monument were made for San Francisco, Cleveland, Milwaukee and Syracuse and erected in parks in those cities. I laughed some more when I found that out. Is there such a thing as jealous laughter?

A friend of mine used to joke that women writers discovered friendship in 2015, when the last volume of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet came out. I laughed, but I knew what he meant. It is easy to think of men who navigated the literary world together: Jonson and Shakespeare, Wordsworth and Coleridge, Johnson and Boswell, Shelley and Byron, Marx and Engels, Sartre and Camus, Bellow and Roth, Hughes and Heaney, Amis and Barnes. In Weimar for a day in summer 2014, bitter laughter rose in me when I emerged into Theaterplatz to find a monument to literary bro-dom: Goethe and Schiller in bronze, each with a hand on a shared crown of laurels. With stout folds in Goethe’s breeches and pupils missing from Schiller’s eyes, the unlovely statue had been cast in 1857, twenty-five years after Goethe died, and had stood for more than a century facing the stage where Goethe had directed many of Schiller’s plays. In the early twentieth century, copies of the monument were made for San Francisco, Cleveland, Milwaukee and Syracuse and erected in parks in those cities. I laughed some more when I found that out. Is there such a thing as jealous laughter? If not for the photographs I might have a hard time believing they ever existed. The pensive infant with the swipe of dark bangs and the black button eyes of a Raggedy Andy doll. The placid baby with the yellow ringlets and the high piping voice. The sturdy toddler with the lower lip that curled into an apostrophe above her chin.

If not for the photographs I might have a hard time believing they ever existed. The pensive infant with the swipe of dark bangs and the black button eyes of a Raggedy Andy doll. The placid baby with the yellow ringlets and the high piping voice. The sturdy toddler with the lower lip that curled into an apostrophe above her chin.

Ana Palacio in Project Syndicate:

Ana Palacio in Project Syndicate: anjay Subramanyam in Sidecar:

anjay Subramanyam in Sidecar: B

B By this point in “King: A Life,” Eig has established his voice. It’s a clean, clear, journalistic voice, one that employs facts the way Saul Bellow said they should be employed, each a wire that sends a current. He does not dispense two-dollar words; he keeps digressions tidy and to a minimum; he jettisons weight, on occasion, for speed. He appears to be so in control of his material that it is difficult to second-guess him.

By this point in “King: A Life,” Eig has established his voice. It’s a clean, clear, journalistic voice, one that employs facts the way Saul Bellow said they should be employed, each a wire that sends a current. He does not dispense two-dollar words; he keeps digressions tidy and to a minimum; he jettisons weight, on occasion, for speed. He appears to be so in control of his material that it is difficult to second-guess him. D

D On a bright summer day in July 2021, James Fisher rested nervously, with a newly shaved head, in a hospital bed surrounded by blinding white lights and surgeons shuffling about in blue scrubs. He was being prepped for an experimental brain surgery at West Virginia University’s Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute, a hulking research facility that overlooks the rolling peaks and cliffs of coal country around Morgantown. The hours-long procedure required impeccable precision, “down to the millimeter,” Fisher’s neurosurgeon, Ali Rezai, told me.

On a bright summer day in July 2021, James Fisher rested nervously, with a newly shaved head, in a hospital bed surrounded by blinding white lights and surgeons shuffling about in blue scrubs. He was being prepped for an experimental brain surgery at West Virginia University’s Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute, a hulking research facility that overlooks the rolling peaks and cliffs of coal country around Morgantown. The hours-long procedure required impeccable precision, “down to the millimeter,” Fisher’s neurosurgeon, Ali Rezai, told me. The writers serve up a heavy dose of fear-mongering: “Advanced AI could represent a profound change in the history of life on Earth,” their second sentence declares, “and should be planned for and managed with commensurate care and resources.”

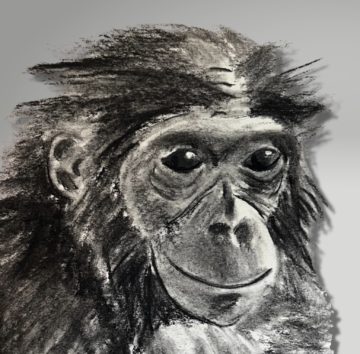

The writers serve up a heavy dose of fear-mongering: “Advanced AI could represent a profound change in the history of life on Earth,” their second sentence declares, “and should be planned for and managed with commensurate care and resources.” I had been volunteering at the ape house for four months before I was invited to meet Nathan. It was December and I’d just spent my first Christmas with the apes. Everyone but the director and I had left for the day. The night sky spilled over the glass-ceilinged, central atrium we called the greenhouse. Despite the snow outside, the greenhouse air was warm and ample. Moving toward the padlocked cage door, I felt light, as if I was about to float up into that dotted black expanse above me, rather than enter a room I’d cleaned feces and orange peels out of hours earlier.

I had been volunteering at the ape house for four months before I was invited to meet Nathan. It was December and I’d just spent my first Christmas with the apes. Everyone but the director and I had left for the day. The night sky spilled over the glass-ceilinged, central atrium we called the greenhouse. Despite the snow outside, the greenhouse air was warm and ample. Moving toward the padlocked cage door, I felt light, as if I was about to float up into that dotted black expanse above me, rather than enter a room I’d cleaned feces and orange peels out of hours earlier. The common definition of free will often has problems when relating to desire and power to choose. An alternative definition that ties free will to different outcomes for life despite one’s past is supported by the probabilistic nature of quantum physics. This definition is compatible with the Many Worlds Interpretation of quantum physics, which refutes the conclusion that randomness does not imply free will.

The common definition of free will often has problems when relating to desire and power to choose. An alternative definition that ties free will to different outcomes for life despite one’s past is supported by the probabilistic nature of quantum physics. This definition is compatible with the Many Worlds Interpretation of quantum physics, which refutes the conclusion that randomness does not imply free will.