Michael Barber in The Paris Review:

Kingsley Amis, the former Angry Young Man, lives in a large, early-nineteenth-century house beside a wooded common. To reach it, one makes a journey similar to that described by the narrator of Girl, 20 when he visits Sir Roy Vandervane: first by tube to the end of the Northern Line at Barnet; then, following a phone call from the station to say where one is, on foot up a stiff slope; and finally down a suburban road. But instead of being picked up en route by Sir Roy’s black chum, Gilbert, I was intercepted by Amis’s tall and imposing blond wife, the novelist Elizabeth Jane Howard.

Kingsley Amis, the former Angry Young Man, lives in a large, early-nineteenth-century house beside a wooded common. To reach it, one makes a journey similar to that described by the narrator of Girl, 20 when he visits Sir Roy Vandervane: first by tube to the end of the Northern Line at Barnet; then, following a phone call from the station to say where one is, on foot up a stiff slope; and finally down a suburban road. But instead of being picked up en route by Sir Roy’s black chum, Gilbert, I was intercepted by Amis’s tall and imposing blond wife, the novelist Elizabeth Jane Howard.

Amis’s study was a picture of bohemian disorder. Scattered across the floor were several teetering piles of poetry books and a mass of old 78 r.p.m. jazz records, while the big Adler typewriter on his desk was almost hidden behind a screen of empty bottles of sparkling wine which he’d recently sampled in his capacity as drink correspondent for Penthouse. A more sober note was struck by some shelves containing a complete Encyclopaedia Britannica, a thirteen-volume O.E.D., and various other authoritative tomes, but this was quickly dispelled by the sight of a small sherry cask in one corner, full, I was told, of whiskey.

More here.

Martin Amis, whose caustic, erudite and bleakly comic novels redefined British fiction in the 1980s and ’90s with their sharp appraisal of tabloid culture and consumer excess, and whose private life made him tabloid fodder himself, died on Friday at his home in Lake Worth, Fla. He was 73.

Martin Amis, whose caustic, erudite and bleakly comic novels redefined British fiction in the 1980s and ’90s with their sharp appraisal of tabloid culture and consumer excess, and whose private life made him tabloid fodder himself, died on Friday at his home in Lake Worth, Fla. He was 73. Nadia Saah in Jewish Currents:

Nadia Saah in Jewish Currents: An interview with Adrienne Buller over at The Syllabus:

An interview with Adrienne Buller over at The Syllabus: Robert N. Watson in LA Review of Books:

Robert N. Watson in LA Review of Books: C

C THE DAY AFTER

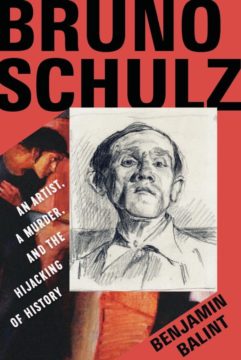

THE DAY AFTER Reading Schulz’s works, it’s easy to see why he might have had such an effect on this array of creative minds. His stories defy description, explication, paraphrase. They are set in a phantasmagoric version of the city of Drohobycz (now in western Ukraine), where Schulz was born and died, and largely in and around the cloth shop on the market square that his parents owned, but in a version of these places where time and space have become molten and malleable. They take place in “years which – like a sixth, smallest toe – grow a 13th freak month” in “an illegal time… liable to all kinds of excesses and crazes”. The narrator’s father – a looming, manic, tragicomic version of Schulz’s own – at one point wastes away to nothing, leaving only “the small shroud of his body” and “a handful of nonsensical oddities”; at another he morphs into “a monstrous, hairy, steel blue horsefly”, a development that the narrator takes in his stride as just one of many “summer aberrations”. The stories read like the quintessence of the human imagination in its densest, strangest form, as if his language were a thick, sweet concentrate of the creativity that other writers dilute to a sippable weakness.

Reading Schulz’s works, it’s easy to see why he might have had such an effect on this array of creative minds. His stories defy description, explication, paraphrase. They are set in a phantasmagoric version of the city of Drohobycz (now in western Ukraine), where Schulz was born and died, and largely in and around the cloth shop on the market square that his parents owned, but in a version of these places where time and space have become molten and malleable. They take place in “years which – like a sixth, smallest toe – grow a 13th freak month” in “an illegal time… liable to all kinds of excesses and crazes”. The narrator’s father – a looming, manic, tragicomic version of Schulz’s own – at one point wastes away to nothing, leaving only “the small shroud of his body” and “a handful of nonsensical oddities”; at another he morphs into “a monstrous, hairy, steel blue horsefly”, a development that the narrator takes in his stride as just one of many “summer aberrations”. The stories read like the quintessence of the human imagination in its densest, strangest form, as if his language were a thick, sweet concentrate of the creativity that other writers dilute to a sippable weakness. It’s rare to come across a new Vietnam War memoir from a major publisher in 2023. Most were written decades ago, when memories were fresh and wounds still raw. That generation of soldiers has begun to pass away.

It’s rare to come across a new Vietnam War memoir from a major publisher in 2023. Most were written decades ago, when memories were fresh and wounds still raw. That generation of soldiers has begun to pass away. The most dangerous political experiment in Latin America is underway in El Salvador. A strange breed of populism is tipping the scale in the region’s age-old tug of war between authoritarianism and democracy. Rather than dividing the country, like populism usually does, it’s uniting it solidly behind a new consensus. More than anything, though, it’s succeeding, and doing so in the kind of impossible-to-miss way that turns heads up and down the hemisphere.

The most dangerous political experiment in Latin America is underway in El Salvador. A strange breed of populism is tipping the scale in the region’s age-old tug of war between authoritarianism and democracy. Rather than dividing the country, like populism usually does, it’s uniting it solidly behind a new consensus. More than anything, though, it’s succeeding, and doing so in the kind of impossible-to-miss way that turns heads up and down the hemisphere. For a long time, people believed that colours were objective, physical properties of objects or of the light that bounced off them. Even today, science teachers regale their students with stories about Isaac Newton and his prism experiment, telling them how different wavelengths of light produce the rainbow of hues around us.

For a long time, people believed that colours were objective, physical properties of objects or of the light that bounced off them. Even today, science teachers regale their students with stories about Isaac Newton and his prism experiment, telling them how different wavelengths of light produce the rainbow of hues around us. For the 20th time since 1933, Congress is writing a multiyear farm bill that will shape what kind of food U.S. farmers grow, how they raise it and how it gets to consumers. These measures are large, complex and expensive: The next farm bill is projected to cost taxpayers

For the 20th time since 1933, Congress is writing a multiyear farm bill that will shape what kind of food U.S. farmers grow, how they raise it and how it gets to consumers. These measures are large, complex and expensive: The next farm bill is projected to cost taxpayers