Amelia Soth at JSTOR Daily:

Of all the sins that might damn your soul for eternity, mumbling is probably pretty far down the list. Still, in medieval Europe, there was a demon for that: Tutivillus, who totted up all the mistakes clergymen made when singing hymns or reciting psalms. Every slurred syllable would be weighed against their souls in the final reckoning.

Of all the sins that might damn your soul for eternity, mumbling is probably pretty far down the list. Still, in medieval Europe, there was a demon for that: Tutivillus, who totted up all the mistakes clergymen made when singing hymns or reciting psalms. Every slurred syllable would be weighed against their souls in the final reckoning.

In one thirteenth-century version of the story, a holy man sees the demon in church, dragging a huge sack. According to a translation by historian Margaret Jennings, “These are the syllables and syncopated words and verses of the psalms which these very clerics in their morning prayers stole from God,” Tutivillus explains. “You can be sure I am keeping these diligently for their accusation.” You can see the scale of the stakes here: a tongue slip was no minor accident; it was theft from God.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Mr. Mamdani, who campaigned on sweeping promises, can build a more positive legacy by focusing on tangible accomplishments. He should take notes from successful mayors, moderate and progressive alike, including

Mr. Mamdani, who campaigned on sweeping promises, can build a more positive legacy by focusing on tangible accomplishments. He should take notes from successful mayors, moderate and progressive alike, including  LONG BEFORE ELON

LONG BEFORE ELON  “Go ahead, tell the end, but please don’t tell the beginning!” begs the movie poster for the 1966 film Gambit. Why would the filmmakers prefer to blow the ending rather than beginning?

“Go ahead, tell the end, but please don’t tell the beginning!” begs the movie poster for the 1966 film Gambit. Why would the filmmakers prefer to blow the ending rather than beginning? When forests are cleared, wetlands drained, and slopes destabilized, entire ecosystems lose their balance. Floods, landslides, and erosion then hit both communities and wildlife alike.

When forests are cleared, wetlands drained, and slopes destabilized, entire ecosystems lose their balance. Floods, landslides, and erosion then hit both communities and wildlife alike. You remember the scene: A camera at a Coldplay concert is showing audience members enjoying the show, with lead singer Chris Martin making a few friendly comments about each fan. The camera cuts to an attractive middle-aged couple in the midst of a cute embrace, with the man holding the woman from behind as they sway to the music. Then the couple spots the Jumbotron, and a perfectly choreographed series of panicked actions unfolds. The woman, shocked, covers her face, and turns away from the camera. The man dives to his left, out of the camera’s view. A younger woman, sitting behind them, and evidently in the know about what is happening, comes into view, the look on her face a poetic mix of horror and glee. “Oh, what?” Martin comments. “Either they’re having an affair or they’re just very shy.”

You remember the scene: A camera at a Coldplay concert is showing audience members enjoying the show, with lead singer Chris Martin making a few friendly comments about each fan. The camera cuts to an attractive middle-aged couple in the midst of a cute embrace, with the man holding the woman from behind as they sway to the music. Then the couple spots the Jumbotron, and a perfectly choreographed series of panicked actions unfolds. The woman, shocked, covers her face, and turns away from the camera. The man dives to his left, out of the camera’s view. A younger woman, sitting behind them, and evidently in the know about what is happening, comes into view, the look on her face a poetic mix of horror and glee. “Oh, what?” Martin comments. “Either they’re having an affair or they’re just very shy.” In a 1990 review

In a 1990 review How can whole societies come to believe that the dead walk among them? Understanding that requires moving beyond theoretical approaches and engaging with tangible human communities and their world-views. We will first visit two very different societies in which the veil between life and death has been thin. The dead have been close: sometimes to be revered, sometimes to be feared, but regularly to be interacted with, if not unambiguously in a bodily form. Both case-studies manifest an endemic layer of anxiety, capable of intensifying under stress into something more concentrated and physical.

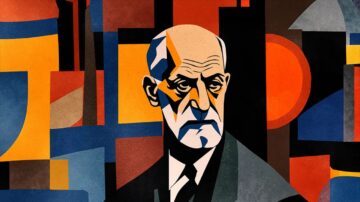

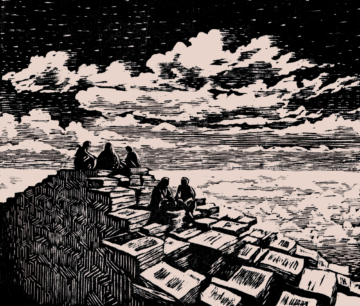

How can whole societies come to believe that the dead walk among them? Understanding that requires moving beyond theoretical approaches and engaging with tangible human communities and their world-views. We will first visit two very different societies in which the veil between life and death has been thin. The dead have been close: sometimes to be revered, sometimes to be feared, but regularly to be interacted with, if not unambiguously in a bodily form. Both case-studies manifest an endemic layer of anxiety, capable of intensifying under stress into something more concentrated and physical. We associate Freud with the repression of thoughts and feelings. But he also described a subtler defense: recognizing an uncomfortable truth, yet acting as if it didn’t matter—a phenomenon he called disavowal. In this interview, philosopher Alenka Zupančič, a close collaborator of Slavoj Žižek, argues that disavowal is the key to understanding our political paralysis. From climate change to populism to the performative outrage of social media, Zupančič says the problem isn’t that we deny reality—it’s that we acknowledge it endlessly and keep doing nothing.

We associate Freud with the repression of thoughts and feelings. But he also described a subtler defense: recognizing an uncomfortable truth, yet acting as if it didn’t matter—a phenomenon he called disavowal. In this interview, philosopher Alenka Zupančič, a close collaborator of Slavoj Žižek, argues that disavowal is the key to understanding our political paralysis. From climate change to populism to the performative outrage of social media, Zupančič says the problem isn’t that we deny reality—it’s that we acknowledge it endlessly and keep doing nothing. W

W I remember the vogue in the ’60s and ’70s for critical essays predicting the imminent “death of the novel.” In

I remember the vogue in the ’60s and ’70s for critical essays predicting the imminent “death of the novel.” In  It’s not that the AI companies are growing their computing power slowly — surprise at the lack of compute put into new training reflects how aggressively they’ve scaled until now. Releasing a one hundred times larger model every two years would demand a tenfold increase in capacity each year, which, You says, is unrealistic. A new model every three years, he says, might be feasible, though that still requires an ambitious five-fold increase in compute every year.

It’s not that the AI companies are growing their computing power slowly — surprise at the lack of compute put into new training reflects how aggressively they’ve scaled until now. Releasing a one hundred times larger model every two years would demand a tenfold increase in capacity each year, which, You says, is unrealistic. A new model every three years, he says, might be feasible, though that still requires an ambitious five-fold increase in compute every year. In 1987, Lei Jun 雷军 was a 21-year-old student in Wuhan University’s computer science program. The book that had set his imagination alight was Fire in the Valley 硅谷之火, which chronicles the evolution of 1970s homebrew hacker culture into global titans like Apple, Microsoft, and IBM. The heroes of that story, of course, were visionaries like Steve Jobs. Lei Jun’s trajectory — he founded

In 1987, Lei Jun 雷军 was a 21-year-old student in Wuhan University’s computer science program. The book that had set his imagination alight was Fire in the Valley 硅谷之火, which chronicles the evolution of 1970s homebrew hacker culture into global titans like Apple, Microsoft, and IBM. The heroes of that story, of course, were visionaries like Steve Jobs. Lei Jun’s trajectory — he founded