Oliver Wang at The Current:

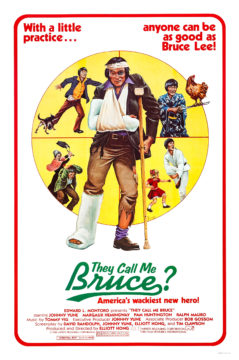

In the conventional canon of Asian American cinema, you’re unlikely to find They Call Me Bruce mentioned. This is in spite of the fact that it arrived right after Wayne Wang’s lauded debut, Chan Is Missing (1982), as arguably the second Asian American feature to ever gain theatrical distribution (and probably the first to turn a substantial profit). This makes its absence from the canon all the more curious, and both They Call Me Bruce and its primary creators are overdue a reconsideration.

In the conventional canon of Asian American cinema, you’re unlikely to find They Call Me Bruce mentioned. This is in spite of the fact that it arrived right after Wayne Wang’s lauded debut, Chan Is Missing (1982), as arguably the second Asian American feature to ever gain theatrical distribution (and probably the first to turn a substantial profit). This makes its absence from the canon all the more curious, and both They Call Me Bruce and its primary creators are overdue a reconsideration.

Like their film, Elliott Hong and Johnny Yune are fascinating but largely forgotten. Hong, in particular, is an enigma; it’s hard to find much information about the Korean American filmmaker, though he directed several features—mostly independently produced action movies—beginning with Kill the Golden Goose (1979). They Call Me Bruce’s B-movie trappings—cheap production design, amateur action choreography—tend to fall somewhere between “so bad they’re good” and “just plain bad,” but it’s important to think about the film as a reflection of both its era and its limited budget, both of which have contributed to its neglect.

more here.

It wasn’t the singing; it was the song. When Deanie Parker hit her last high note in the studio, and the band’s final chord faded behind her, the producer gave her a long, appraising look. She’d be great onstage, with those sugarplum features and defiant eyes, and that voice could knock down walls. “You sound good,” he said. “But if we’re going to cut a record, you’ve got to have your own song. A song that you created. We can’t introduce a new artist covering somebody else’s song.” Did she have any original material? Parker stared at him blankly for a moment, then shook her head.

It wasn’t the singing; it was the song. When Deanie Parker hit her last high note in the studio, and the band’s final chord faded behind her, the producer gave her a long, appraising look. She’d be great onstage, with those sugarplum features and defiant eyes, and that voice could knock down walls. “You sound good,” he said. “But if we’re going to cut a record, you’ve got to have your own song. A song that you created. We can’t introduce a new artist covering somebody else’s song.” Did she have any original material? Parker stared at him blankly for a moment, then shook her head. Birders are a funny bunch, mostly—at this festival, anyway—white, older-aged, and of a delightfully inefficient temperament. In general, they talk and move at a relaxed pace, and are eager to dedicate long moments of their lives to matters that many people simply whisk past. On a geology tour my mom and I took on our third day in Hays, the group revolted and made the guide turn the van around just to take pictures of a flock of turkeys. Later, about a half hour was spent on a quiet debate over whether a falcon in a far-off tree was a kestrel or a much more uncommon merlin. I listened to a man trying in vain for several minutes to describe the position of the falcon to the woman next to him: “It’s in the backmost tree, up there on the white branch. There are a lot of light branches. But no! There’s only one white branch.” Over the course of the trip, time seemed to slow down to match the geologic scale suggested by the ancient mating rituals of the prairie chickens and the landscape that surrounds them: sprawling fields of grass punctuated by chalk formations left over from Kansas’s past beneath the Cretaceous-era Western Interior Seaway.

Birders are a funny bunch, mostly—at this festival, anyway—white, older-aged, and of a delightfully inefficient temperament. In general, they talk and move at a relaxed pace, and are eager to dedicate long moments of their lives to matters that many people simply whisk past. On a geology tour my mom and I took on our third day in Hays, the group revolted and made the guide turn the van around just to take pictures of a flock of turkeys. Later, about a half hour was spent on a quiet debate over whether a falcon in a far-off tree was a kestrel or a much more uncommon merlin. I listened to a man trying in vain for several minutes to describe the position of the falcon to the woman next to him: “It’s in the backmost tree, up there on the white branch. There are a lot of light branches. But no! There’s only one white branch.” Over the course of the trip, time seemed to slow down to match the geologic scale suggested by the ancient mating rituals of the prairie chickens and the landscape that surrounds them: sprawling fields of grass punctuated by chalk formations left over from Kansas’s past beneath the Cretaceous-era Western Interior Seaway. O

O The

The For at least the last 400 million years, insects have ruled the world. The first insect fossils are nearly twice as old as the oldest dinosaur. They were the first animals to fly, and that adaptation helped them to spread to every corner of the planet. They survived four of the five mass extinctions in Earth’s history. Then, a mere 200,000 years ago, a new species appeared in East Africa and started to spread over the surface of their planet. In a geologic blink, modern humans were everywhere, hunting and farming and changing the world to fit our needs and desires. It was inevitable that these two dominant animals would come to affect each other in profound ways, both positive and negative.

For at least the last 400 million years, insects have ruled the world. The first insect fossils are nearly twice as old as the oldest dinosaur. They were the first animals to fly, and that adaptation helped them to spread to every corner of the planet. They survived four of the five mass extinctions in Earth’s history. Then, a mere 200,000 years ago, a new species appeared in East Africa and started to spread over the surface of their planet. In a geologic blink, modern humans were everywhere, hunting and farming and changing the world to fit our needs and desires. It was inevitable that these two dominant animals would come to affect each other in profound ways, both positive and negative. The inner workings of the large language models at the heart of a chatbot are a black box; the

The inner workings of the large language models at the heart of a chatbot are a black box; the  I briefly moved back to Rhode Island following the collapse of my first marriage. It was the summer before I turned twenty-seven, and I spent three months hiding away in my childhood bedroom, grief-damaged and humiliated by the task of trying to figure out who and how I was supposed to be. My husband and I had managed to stay married for only four years, the last of which I spent watching from the sidelines as he enjoyed an unexpectedly rapid and very public rise as an artist. His newly minted success introduced a host of newly minted problems, and I drifted through most of that winter and spring weeping in the utility closet at the boutique where I worked and asking him where I fit into his life so many times that I eventually didn’t fit into it at all.

I briefly moved back to Rhode Island following the collapse of my first marriage. It was the summer before I turned twenty-seven, and I spent three months hiding away in my childhood bedroom, grief-damaged and humiliated by the task of trying to figure out who and how I was supposed to be. My husband and I had managed to stay married for only four years, the last of which I spent watching from the sidelines as he enjoyed an unexpectedly rapid and very public rise as an artist. His newly minted success introduced a host of newly minted problems, and I drifted through most of that winter and spring weeping in the utility closet at the boutique where I worked and asking him where I fit into his life so many times that I eventually didn’t fit into it at all. Plastic recycling doesn’t work, no matter how diligently you wash out your peanut butter container. Only about

Plastic recycling doesn’t work, no matter how diligently you wash out your peanut butter container. Only about  In conversation with the novelist

In conversation with the novelist  The people of Rwanda have been tested by tragedy. Nearly thirty years ago, when ethnic Hutu extremists sought to exterminate the country’s Tutsi minority,

The people of Rwanda have been tested by tragedy. Nearly thirty years ago, when ethnic Hutu extremists sought to exterminate the country’s Tutsi minority,  In 1989, a redheaded mermaid made her big-screen debut. She wanted to be part of the above-surface world, where people walk around on (what do you call ‘em?) feet, to wander free on the sand in the sunshine. She fell in love with a handsome, kind prince. After some terrifying obstacles and a near-miss, they married. Ariel got her feet. For Disney, The Little Mermaid was a big hit, the start of a new era for the studio’s animated entertainment. She launched a hot streak that would continue through the 1990s: Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), The Lion King (1994), Pocahontas (1995), The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1996), Hercules (1997), Mulan (1998), and Tarzan (1999). They were hits then, the early films in particular, and form a foundational plank in billions of lives. A tremendous percentage of people walking around on the planet can sing snatches of “Part of Your World” or “A Whole New World” or “Circle of Life” at the drop of a hat.

In 1989, a redheaded mermaid made her big-screen debut. She wanted to be part of the above-surface world, where people walk around on (what do you call ‘em?) feet, to wander free on the sand in the sunshine. She fell in love with a handsome, kind prince. After some terrifying obstacles and a near-miss, they married. Ariel got her feet. For Disney, The Little Mermaid was a big hit, the start of a new era for the studio’s animated entertainment. She launched a hot streak that would continue through the 1990s: Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), The Lion King (1994), Pocahontas (1995), The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1996), Hercules (1997), Mulan (1998), and Tarzan (1999). They were hits then, the early films in particular, and form a foundational plank in billions of lives. A tremendous percentage of people walking around on the planet can sing snatches of “Part of Your World” or “A Whole New World” or “Circle of Life” at the drop of a hat. Scientists might be able to keep tabs on the world’s flora and fauna by analysing DNA floating through the air. That’s the conclusion of a study published on 5 June in Current Biology

Scientists might be able to keep tabs on the world’s flora and fauna by analysing DNA floating through the air. That’s the conclusion of a study published on 5 June in Current Biology