Colin Dickey at Atlas Obscura:

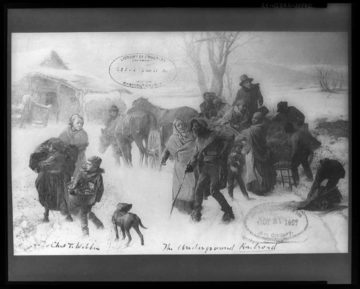

Even today, no one is even sure precisely where the name originated. Some have traced it to an account from 1839, when a young Black man was caught “lurking” around the Capitol in Washington, D.C.—when asked how he got there, he said that he had been sent north by a “railroad which went underground all the way to Boston.”

Even today, no one is even sure precisely where the name originated. Some have traced it to an account from 1839, when a young Black man was caught “lurking” around the Capitol in Washington, D.C.—when asked how he got there, he said that he had been sent north by a “railroad which went underground all the way to Boston.”

Through a loose network of formerly enslaved and free Black Americans, along with their white allies, thousands of enslaved Americans made their way north in the decades before the Civil War, moving sometimes surreptitiously, sometimes out in the open, on railways and ships, in wagons and freight, toward freedom. It is impossible now to know for certain how many people made their way out of slavery on the Underground Railroad; both supporters and detractors had an investment in embellishing its impact. In the North, abolitionists dramatized the plight of those seeking refuge and to play up their own heroic efforts. In the South, enslavers argued that the Underground Railroad was nothing short of a grand conspiracy of subversive lawbreakers—the higher the numbers, the greater the threat to the country.

more here.

The Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges lost his vision—what he called his “reader’s and writer’s sight”—around the same time that he became the director of the National Library of Argentina. This put him in charge of nearly a million books, he observed, at the very moment he could no longer read them.

The Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges lost his vision—what he called his “reader’s and writer’s sight”—around the same time that he became the director of the National Library of Argentina. This put him in charge of nearly a million books, he observed, at the very moment he could no longer read them. If you feed America’s most important legal document—the

If you feed America’s most important legal document—the  In 1950, Eleanor Roosevelt, serving as the first Chairperson of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, was involved in a bitter

In 1950, Eleanor Roosevelt, serving as the first Chairperson of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, was involved in a bitter  The Quick and the Dead, which is not set in Florida but in the West, is one of the weirdest, funniest, darkest novels you’ll ever read. It lost the 2001 Pulitzer Prize to The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, thus fulfilling the promise of Luke 4:24. Williams’s new novel, Harrow, is Quick’s spiritual successor, perhaps even sequel, taking up that novel’s concerns and amplifying them by the full twenty years it took her to write it. Harrow reminds me very much of Denis Johnson’s Fiskadoro and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, but, with apologies to the boys, it’s better than both of their novels put together. Harrow belongs at the front of the pack of recent climate fiction, even as it refuses the basic premise (human survival is important) and the sentimental rays of hope (another world is possible!) that are the hallmarks of the genre. This novel doesn’t care who you vote for or if you recycle. It’s not bullish on green tech jobs or sustainable meat. It would leave Steven “Things Are Getting Better” Pinker and Matthew “One Billion Americans” Yglesias writhing in shame if guys like them were capable of reading novels or feeling shame. Harrow is a crabby, craggy, comfortless, arid, erudite, obtuse, perfect novel, a singular entry in a singular body of work by an artist of uncompromised originality and vision. For all of its fragmentation and deliberate strategies of estrangement, Harrow feels coherent and complete, like a single long-form thought or a religious epiphany. It’s also funny as hell.

The Quick and the Dead, which is not set in Florida but in the West, is one of the weirdest, funniest, darkest novels you’ll ever read. It lost the 2001 Pulitzer Prize to The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, thus fulfilling the promise of Luke 4:24. Williams’s new novel, Harrow, is Quick’s spiritual successor, perhaps even sequel, taking up that novel’s concerns and amplifying them by the full twenty years it took her to write it. Harrow reminds me very much of Denis Johnson’s Fiskadoro and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, but, with apologies to the boys, it’s better than both of their novels put together. Harrow belongs at the front of the pack of recent climate fiction, even as it refuses the basic premise (human survival is important) and the sentimental rays of hope (another world is possible!) that are the hallmarks of the genre. This novel doesn’t care who you vote for or if you recycle. It’s not bullish on green tech jobs or sustainable meat. It would leave Steven “Things Are Getting Better” Pinker and Matthew “One Billion Americans” Yglesias writhing in shame if guys like them were capable of reading novels or feeling shame. Harrow is a crabby, craggy, comfortless, arid, erudite, obtuse, perfect novel, a singular entry in a singular body of work by an artist of uncompromised originality and vision. For all of its fragmentation and deliberate strategies of estrangement, Harrow feels coherent and complete, like a single long-form thought or a religious epiphany. It’s also funny as hell. After hundreds of hours listening to thousands of wolves for my PhD, the difference between howls was obvious. The voice of a Russian wolf was nothing like that of a Canadian, and a jackal was so utterly different again that it was like listening to Farsi and French. I believed that there must be geographic and subspecies distinctions. Other researchers had made this proposition before, but no one had put together a large enough collection of howls to test it properly. A few years later, my degree finished, I told my Dracula story to the zoologist Arik Kershenbaum at the University of Cambridge. He promptly suggested we explore how attuned to wolves I really am. Are there differences between canid species and subspecies and, if so, could these reflect diverging cultures?

After hundreds of hours listening to thousands of wolves for my PhD, the difference between howls was obvious. The voice of a Russian wolf was nothing like that of a Canadian, and a jackal was so utterly different again that it was like listening to Farsi and French. I believed that there must be geographic and subspecies distinctions. Other researchers had made this proposition before, but no one had put together a large enough collection of howls to test it properly. A few years later, my degree finished, I told my Dracula story to the zoologist Arik Kershenbaum at the University of Cambridge. He promptly suggested we explore how attuned to wolves I really am. Are there differences between canid species and subspecies and, if so, could these reflect diverging cultures? A study that followed thousands of people over 25 years has identified proteins linked to the development of dementia if their levels are unbalanced during middle age. The findings, published in Science Translational Medicine on 19 July

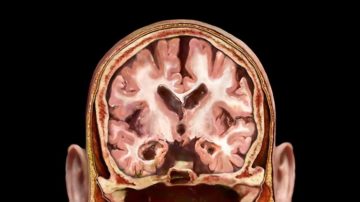

A study that followed thousands of people over 25 years has identified proteins linked to the development of dementia if their levels are unbalanced during middle age. The findings, published in Science Translational Medicine on 19 July Life finds a way.

Life finds a way. “The problem that troubles the novelist [is] how to justify a concern with morally dubious people in a contemptible activity,” notes South African writer J. M. Coetzee, “ … how to treat something that, in truth, because it is offered like the Gorgon’s head to terrorize the populace and paralyze resistance, deserves to be ignored.” Here, in the essay “Into the Dark Chamber,” Coetzee points out that literature exposing political terror—in this case, torture, the existence of which is repeatedly denied by repressive regimes—can actually become an inadvertent tool of that terror.

“The problem that troubles the novelist [is] how to justify a concern with morally dubious people in a contemptible activity,” notes South African writer J. M. Coetzee, “ … how to treat something that, in truth, because it is offered like the Gorgon’s head to terrorize the populace and paralyze resistance, deserves to be ignored.” Here, in the essay “Into the Dark Chamber,” Coetzee points out that literature exposing political terror—in this case, torture, the existence of which is repeatedly denied by repressive regimes—can actually become an inadvertent tool of that terror. “How does this indictment affect his candidacy?” Bill Hemmer, of Fox News, asked the former South Carolina governor Nikki Haley last week. The candidacy in question was, of course, that of former President Donald Trump. The indictment being discussed was one that Trump, in a Truth Social post last week, said he expected any day after receiving a so-called target letter from the special counsel Jack Smith, on charges related to Trump’s actions in the prelude to the January 6, 2021, assault on the Capitol. It would be his third criminal indictment in about four months. And, Haley told Hemmer, “it’s going to keep on going. I mean, the rest of this primary election is going to be in reference to Trump, it’s going to be about lawsuits, it’s going to be about legal fees, it’s going to be about judges, and it’s just going to continue to be a further and further distraction.”

“How does this indictment affect his candidacy?” Bill Hemmer, of Fox News, asked the former South Carolina governor Nikki Haley last week. The candidacy in question was, of course, that of former President Donald Trump. The indictment being discussed was one that Trump, in a Truth Social post last week, said he expected any day after receiving a so-called target letter from the special counsel Jack Smith, on charges related to Trump’s actions in the prelude to the January 6, 2021, assault on the Capitol. It would be his third criminal indictment in about four months. And, Haley told Hemmer, “it’s going to keep on going. I mean, the rest of this primary election is going to be in reference to Trump, it’s going to be about lawsuits, it’s going to be about legal fees, it’s going to be about judges, and it’s just going to continue to be a further and further distraction.” The bird has many names, often divinely inspired: the Lord God Bird, the Lazarus Bird, the Ghost Bird, the Grail Bird. Bobby Harrison is a religious man, but he doesn’t like any of them. He prefers to call it what it is: an ivory-billed woodpecker. “Well,” he says with a shrug, “it is just a bird, after all.”

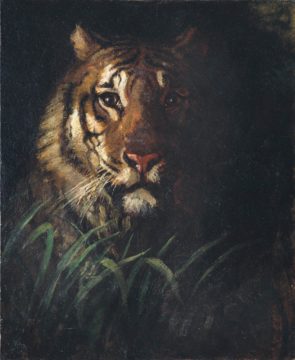

The bird has many names, often divinely inspired: the Lord God Bird, the Lazarus Bird, the Ghost Bird, the Grail Bird. Bobby Harrison is a religious man, but he doesn’t like any of them. He prefers to call it what it is: an ivory-billed woodpecker. “Well,” he says with a shrug, “it is just a bird, after all.” I have learned much about your world in the three months since my form changed. That you swim in an ocean of language. Words pour from your mouths, your screens. Your cities are brightly lit and never silent, but you speak so much and so often, you have forgotten what it is to rest in quietness. The moon’s passage across the skies means nothing to you, carries no messages of comfort or danger. The earth’s speech, its invitations and enchantments, its tremors and its warnings, the whispers of tree roots snaking underneath the surface of your roads and apartments, these are lost to most of you. I have learned that you fear darkness and never seek to explore its many gifts. You can see, hear, feel, speak, but you do not live in your senses. You live like so many leaves in the storm, blown here, blown there.

I have learned much about your world in the three months since my form changed. That you swim in an ocean of language. Words pour from your mouths, your screens. Your cities are brightly lit and never silent, but you speak so much and so often, you have forgotten what it is to rest in quietness. The moon’s passage across the skies means nothing to you, carries no messages of comfort or danger. The earth’s speech, its invitations and enchantments, its tremors and its warnings, the whispers of tree roots snaking underneath the surface of your roads and apartments, these are lost to most of you. I have learned that you fear darkness and never seek to explore its many gifts. You can see, hear, feel, speak, but you do not live in your senses. You live like so many leaves in the storm, blown here, blown there. The president of Stanford University, Marc Tessier-Lavigne, recently announced his impending resignation after the university’s board of trustees found data manipulations in academic papers he co-authored. Though there reportedly were rumors of manipulated information in those papers, Stanford’s student newspaper,

The president of Stanford University, Marc Tessier-Lavigne, recently announced his impending resignation after the university’s board of trustees found data manipulations in academic papers he co-authored. Though there reportedly were rumors of manipulated information in those papers, Stanford’s student newspaper,  Professor Russell Foster CBE, head of the

Professor Russell Foster CBE, head of the