Shannon Palus in Slate:

But this week, like so many of us, I’ve been thinking about the other direction that can apply to that comment about Silicon Valley—what happens when the goal, having achieved so much else, is not extending life, but risking it? Because if placing a bet on living forever is one leisure activity to put your vast wealth toward, another is extreme feats of travel. The rich people of today can buy tickets to outer space. Or to the deep ocean. Where things can go very wrong, very quickly.

But this week, like so many of us, I’ve been thinking about the other direction that can apply to that comment about Silicon Valley—what happens when the goal, having achieved so much else, is not extending life, but risking it? Because if placing a bet on living forever is one leisure activity to put your vast wealth toward, another is extreme feats of travel. The rich people of today can buy tickets to outer space. Or to the deep ocean. Where things can go very wrong, very quickly.

Scrambling to make sense of the unfolding submersible tragedy—it is very strange to know a group of people only has a handful of oxygen hours left—writers, including this one, turned our attention to the sheer cost of it all: tickets aboard OceanGate’s Titan were $250,000 a pop. Interestingly, that’s double what the CEO originally charged—he set the price tag to be more on par with space travel, after realizing his offering, a seatless minivan-sized can that dips to wild depths, really was similar to space travel.

Did the people floating with—checks the live blogs—20 hours of oxygen left now know what they were getting into when they boarded the vessel? A video clip of David Pogue, who took a press trip aboard the Titan last summer for CBS, went viral. He flipped through the waiver form, and told the camera: “An experimental submersible vessel that has not been approved or certified by any regulatory body and could result in physical injury, disability, emotional trauma, or death. Where do I sign?”

More here.

B

B MIRCEA

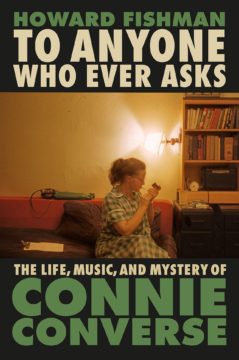

MIRCEA  CONNIE CONVERSE is remembered now, if at all, as a rediscovered relic of blog-era music oddity. Like Rodriguez, Donnie and Joe Emerson, Sibylle Baier, Lavender Country, or Converse’s near-contemporary and kindred spirit, Molly Drake, the cracks she slipped through became her calling card. Converse was notable for preserving a greater level of obscurity more extreme than any of the others: recordings never commercially available; no connections to any scene or famous figure; being a guitar-playing singer-songwriter (and home-taper) in the early 1950s, before such a thing existed, who played only among friends before dropping out of music in the 1960s and ultimately disappearing shortly after. It was not until the 2000s that some of her work was finally made available for those who were never in a room with her.

CONNIE CONVERSE is remembered now, if at all, as a rediscovered relic of blog-era music oddity. Like Rodriguez, Donnie and Joe Emerson, Sibylle Baier, Lavender Country, or Converse’s near-contemporary and kindred spirit, Molly Drake, the cracks she slipped through became her calling card. Converse was notable for preserving a greater level of obscurity more extreme than any of the others: recordings never commercially available; no connections to any scene or famous figure; being a guitar-playing singer-songwriter (and home-taper) in the early 1950s, before such a thing existed, who played only among friends before dropping out of music in the 1960s and ultimately disappearing shortly after. It was not until the 2000s that some of her work was finally made available for those who were never in a room with her. Except for a painful one-year stint as a high-school teacher of philosophy in his native Romania, Emil Cioran never had a real job. ‘I avoided at any price the humiliation of a career,’ he observed toward the end of his life. ‘I preferred to live like a parasite [rather] than to destroy myself by keeping a job.’ When he chose to move to France, in 1937, it mattered to him that Paris was ‘the only city in the world where you could be poor without being ashamed of it, without complications, without dramas.’

Except for a painful one-year stint as a high-school teacher of philosophy in his native Romania, Emil Cioran never had a real job. ‘I avoided at any price the humiliation of a career,’ he observed toward the end of his life. ‘I preferred to live like a parasite [rather] than to destroy myself by keeping a job.’ When he chose to move to France, in 1937, it mattered to him that Paris was ‘the only city in the world where you could be poor without being ashamed of it, without complications, without dramas.’ Four years ago, physicists at Google claimed their quantum computer could outperform classical machines — although only at a niche calculation with no practical applications. Now their counterparts at IBM say they have evidence that quantum computers will soon beat ordinary ones at useful tasks, such as calculating properties of materials or the interactions of elementary particles.

Four years ago, physicists at Google claimed their quantum computer could outperform classical machines — although only at a niche calculation with no practical applications. Now their counterparts at IBM say they have evidence that quantum computers will soon beat ordinary ones at useful tasks, such as calculating properties of materials or the interactions of elementary particles. The

The  There’s no more powerful mind-altering substance than a book. Five years ago, Michael Pollan wrote

There’s no more powerful mind-altering substance than a book. Five years ago, Michael Pollan wrote  The capabilities of a new class of tools, colloquially known as generative

The capabilities of a new class of tools, colloquially known as generative  Parfit never became a well-known public intellectual, but within English-speaking academe he is acknowledged as one of the most important philosophers of the late 20th century. He made his name with a single journal paper that breathed new life into an old problem that had drifted into obscurity, mainly because no one had anything new to say about it. The problem was: what needs to be true to correctly identify a person as the same person at two different times?

Parfit never became a well-known public intellectual, but within English-speaking academe he is acknowledged as one of the most important philosophers of the late 20th century. He made his name with a single journal paper that breathed new life into an old problem that had drifted into obscurity, mainly because no one had anything new to say about it. The problem was: what needs to be true to correctly identify a person as the same person at two different times? Biology faces a grave threat from “progressive” politics that are changing the way our work is done, delimiting areas of biology that are taboo and will not be funded by the government or published in scientific journals, stipulating what words biologists must avoid in their writing, and decreeing how biology is taught to students and communicated to other scientists and the public through the technical and popular press. We wrote this article not to argue that biology is dead, but to show how ideology is poisoning it. The science that has brought us so much progress and understanding—from the structure of DNA to the green revolution and the design of COVID-19 vaccines—is endangered by political dogma strangling our essential tradition of open research and scientific communication. And because much of what we discuss occurs within academic science, where many scientists are too cowed to speak their minds, the public is largely unfamiliar with these issues. Sadly, by the time they become apparent to everyone, it might be too late.

Biology faces a grave threat from “progressive” politics that are changing the way our work is done, delimiting areas of biology that are taboo and will not be funded by the government or published in scientific journals, stipulating what words biologists must avoid in their writing, and decreeing how biology is taught to students and communicated to other scientists and the public through the technical and popular press. We wrote this article not to argue that biology is dead, but to show how ideology is poisoning it. The science that has brought us so much progress and understanding—from the structure of DNA to the green revolution and the design of COVID-19 vaccines—is endangered by political dogma strangling our essential tradition of open research and scientific communication. And because much of what we discuss occurs within academic science, where many scientists are too cowed to speak their minds, the public is largely unfamiliar with these issues. Sadly, by the time they become apparent to everyone, it might be too late. New technologies can change the global balance of power. Nuclear weapons divided the world into haves and have-nots. The Industrial Revolution allowed Europe to race ahead in economic and military power, spurring a wave of colonial expansion. A central question in the artificial intelligence revolution is who will benefit: Who will be able to access this powerful new technology, and who will be left behind?

New technologies can change the global balance of power. Nuclear weapons divided the world into haves and have-nots. The Industrial Revolution allowed Europe to race ahead in economic and military power, spurring a wave of colonial expansion. A central question in the artificial intelligence revolution is who will benefit: Who will be able to access this powerful new technology, and who will be left behind? In “Monet/Mitchell: Painting the French Landscape,” on view at the St. Louis Art Museum through June 25, the enduring impact of Monet’s vision hits hard. I mean both his literal and artistic vision—these were inextricable for the plein air painter. The show highlights the rhymes between his work and that of the American Abstract Expressionist Joan Mitchell (1925–1992), focusing specifically on works both artists made in the gardens of Vétheuil, in northern France.

In “Monet/Mitchell: Painting the French Landscape,” on view at the St. Louis Art Museum through June 25, the enduring impact of Monet’s vision hits hard. I mean both his literal and artistic vision—these were inextricable for the plein air painter. The show highlights the rhymes between his work and that of the American Abstract Expressionist Joan Mitchell (1925–1992), focusing specifically on works both artists made in the gardens of Vétheuil, in northern France. Cormac McCarthy’s work means a lot to me, though when I try to explain exactly what, I find myself unusually stymied; my affinity for him doesn’t make all that much sense to me. What connection do I have with the landscapes he conjures? What knowledge do I have of the kind of violence that is the subject and the fabric of many of his books? What place do I find in a world that is, among other things, nearly entirely masculine, hostile, rife with true desperation? The answer is none—unlike with much of my reading, I do not seek a mirror in McCarthy’s worldview—and yet there is something in its aesthetic articulation that has always resonated with me. (I have a curious memory of reading The Road over my mom’s shoulder when I must have been about ten.) I have a passage from All The Pretty Horses saved on my desktop, which I have revisited often and send around now and again, and which I cannot quote in full here but which ends:

Cormac McCarthy’s work means a lot to me, though when I try to explain exactly what, I find myself unusually stymied; my affinity for him doesn’t make all that much sense to me. What connection do I have with the landscapes he conjures? What knowledge do I have of the kind of violence that is the subject and the fabric of many of his books? What place do I find in a world that is, among other things, nearly entirely masculine, hostile, rife with true desperation? The answer is none—unlike with much of my reading, I do not seek a mirror in McCarthy’s worldview—and yet there is something in its aesthetic articulation that has always resonated with me. (I have a curious memory of reading The Road over my mom’s shoulder when I must have been about ten.) I have a passage from All The Pretty Horses saved on my desktop, which I have revisited often and send around now and again, and which I cannot quote in full here but which ends: