Temple Grandin in The New York Times:

In “Planta Sapiens,” Paco Calvo, a philosopher of plant behavior, and his co-author, Natalie Lawrence, present the idea that flora are intelligent — that is, capable of cognition. In Calvo’s opinion, people pay more attention to animals than plants and this may explain why some of plants’ remarkable abilities have been overlooked. Our evolutionary history may also shape our reduced attention to the subject; plants are, after all, unlikely to attack people.

In “Planta Sapiens,” Paco Calvo, a philosopher of plant behavior, and his co-author, Natalie Lawrence, present the idea that flora are intelligent — that is, capable of cognition. In Calvo’s opinion, people pay more attention to animals than plants and this may explain why some of plants’ remarkable abilities have been overlooked. Our evolutionary history may also shape our reduced attention to the subject; plants are, after all, unlikely to attack people.

Research shows that we are more likely to focus on rapidly presented pictures of animals than those of plants. Studies also demonstrate that while children quickly learn that both humans and animals are living beings, it takes them longer to understand the same thing about plants — indeed, many children do not comprehend it until they are around 10 years old. Calvo refers to this human tendency by a term coined in the 1990s: “plant blindness.”

More here.

Patrick Bigger and Federico Sibaja in Phenomenal World:

Patrick Bigger and Federico Sibaja in Phenomenal World: Tim Sahay in Foreign Policy:

Tim Sahay in Foreign Policy: Timothy Andersen in Aeon:

Timothy Andersen in Aeon: Vowell’s unforgettable early contribution to a relatively early incarnation of This American Life (back in 1999), in which she performed a similar feat, though that time unfurling the entire history of the United States drawing on the 720 degree panorama (360 degrees of space compounded by 360 degrees of time) available from just one street corner in Chicago. To wit, this one here: Michigan Avenue as it courses over the Chicago River and intersects with Wacker Drive.

Vowell’s unforgettable early contribution to a relatively early incarnation of This American Life (back in 1999), in which she performed a similar feat, though that time unfurling the entire history of the United States drawing on the 720 degree panorama (360 degrees of space compounded by 360 degrees of time) available from just one street corner in Chicago. To wit, this one here: Michigan Avenue as it courses over the Chicago River and intersects with Wacker Drive. One of the strangest, most audacious winks Fear of Kathy Acker bestows is the fact that its contents have little to do with her. Yet Skelley pays substantial tribute to Acker in his introduction, pointing to his own literary puberty in which she was a catalyst: “[H]er vastly funny, scary, sexy portals to expression opened at a susceptible period. […] It was a nascent and fertile moment when Kathy, at the peak of her powers, disrupted me, erupted in me.” After hearing the chapbook discussed on the radio in the 1980s, Acker sent Skelley a postcard that would become a crowning endorsement of the work: “[D]espite my dislike of seeing my own name I think you’re a good writer […] Never what’s expected,” she wrote.

One of the strangest, most audacious winks Fear of Kathy Acker bestows is the fact that its contents have little to do with her. Yet Skelley pays substantial tribute to Acker in his introduction, pointing to his own literary puberty in which she was a catalyst: “[H]er vastly funny, scary, sexy portals to expression opened at a susceptible period. […] It was a nascent and fertile moment when Kathy, at the peak of her powers, disrupted me, erupted in me.” After hearing the chapbook discussed on the radio in the 1980s, Acker sent Skelley a postcard that would become a crowning endorsement of the work: “[D]espite my dislike of seeing my own name I think you’re a good writer […] Never what’s expected,” she wrote. Some years ago, a psychiatrist named Wendy Dean read an article about a physician who died by suicide. Such deaths were distressingly common, she discovered. The suicide rate among doctors appeared to be even higher than the rate among active military members, a notion that startled Dean, who was then working as an administrator at a U.S. Army medical research center in Maryland. Dean started asking the physicians she knew how they felt about their jobs, and many of them confided that they were struggling. Some complained that they didn’t have enough time to talk to their patients because they were too busy filling out electronic medical records. Others bemoaned having to fight with insurers about whether a person with a serious illness would be preapproved for medication. The doctors Dean surveyed were deeply committed to the medical profession. But many of them were frustrated and unhappy, she sensed, not because they were burned out from working too hard but because the health care system made it so difficult to care for their patients.

Some years ago, a psychiatrist named Wendy Dean read an article about a physician who died by suicide. Such deaths were distressingly common, she discovered. The suicide rate among doctors appeared to be even higher than the rate among active military members, a notion that startled Dean, who was then working as an administrator at a U.S. Army medical research center in Maryland. Dean started asking the physicians she knew how they felt about their jobs, and many of them confided that they were struggling. Some complained that they didn’t have enough time to talk to their patients because they were too busy filling out electronic medical records. Others bemoaned having to fight with insurers about whether a person with a serious illness would be preapproved for medication. The doctors Dean surveyed were deeply committed to the medical profession. But many of them were frustrated and unhappy, she sensed, not because they were burned out from working too hard but because the health care system made it so difficult to care for their patients. Hype springs eternal in medicine, but lately the horizon of new possibility seems almost blindingly bright. “I’ve been running my research lab for almost 30 years,” says Jennifer Doudna, a biochemist at the University of California, Berkeley. “And I can say that throughout that period of time, I’ve just never experienced what we’re seeing over just the last five years.”

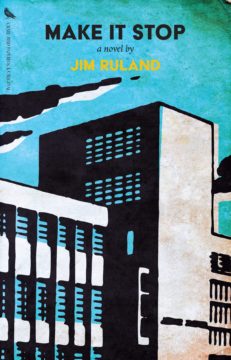

Hype springs eternal in medicine, but lately the horizon of new possibility seems almost blindingly bright. “I’ve been running my research lab for almost 30 years,” says Jennifer Doudna, a biochemist at the University of California, Berkeley. “And I can say that throughout that period of time, I’ve just never experienced what we’re seeing over just the last five years.” TERESE SVOBODA: At first, Make It Stop reads like a fast-paced action adventure with a superhero, but the mission fails, people die. Imagine that in a Bond film! So, while the reader’s gliding along in the narrative, lots of plot builds up, people struggle with sadness and what it’s like to be a hero, particularly an unknown super-ish hero. I love the term “powerless to unfuck” that you use to underscore their struggle. More and more of these heroes in media are presented with complex personalities. Were you influenced by that trend?

TERESE SVOBODA: At first, Make It Stop reads like a fast-paced action adventure with a superhero, but the mission fails, people die. Imagine that in a Bond film! So, while the reader’s gliding along in the narrative, lots of plot builds up, people struggle with sadness and what it’s like to be a hero, particularly an unknown super-ish hero. I love the term “powerless to unfuck” that you use to underscore their struggle. More and more of these heroes in media are presented with complex personalities. Were you influenced by that trend? JIM RULAND: I don’t think so. You see a lot of that stuff in superhero movies, and before the pandemic I’d go see them with my daughter, but I read those comic books when I was her age in the ’80s. I knew from the very beginning that the vigilante group that my character Melanie was a part of would be highly dysfunctional, but I didn’t want it to be superficial. In blockbuster movies, there’s a scene or two where the main character is allowed to be sad and then it’s time to save the world again. Melanie’s world has been ripped apart—much like the narrator of Dog on Fire. What forces shaped your novel?

JIM RULAND: I don’t think so. You see a lot of that stuff in superhero movies, and before the pandemic I’d go see them with my daughter, but I read those comic books when I was her age in the ’80s. I knew from the very beginning that the vigilante group that my character Melanie was a part of would be highly dysfunctional, but I didn’t want it to be superficial. In blockbuster movies, there’s a scene or two where the main character is allowed to be sad and then it’s time to save the world again. Melanie’s world has been ripped apart—much like the narrator of Dog on Fire. What forces shaped your novel? Nineteenth-century final causes were ‘barren virgins’, an aphorism attributed to Francis Bacon, but twentieth-century teleology was a ‘mistress’, an adage of uncertain provenance. A study of historical uses of these gendered metaphors is used to probe changing attitudes toward teleological reasoning in biology. At the beginning of the nineteenth-century, invocations of final causes were commonplace but such idioms are rarely used at its end. This change is commonly attributed to publication of the Origin of Species in 1859 which completed the ejection of final causes from biology. Charles Darwin, however, openly and unashamedly uses teleological reasoning and language in his botanical research. He believed he had naturalized, rather than eliminated, the concept of final cause. A more important reason for the eclipse of final causes was the shift within physiology toward the explanatory modes of the physical sciences which had long held final causes in disrepute. The rejection of final causes as explanatory principles occurred despite a persistence of teleological reasoning that was experienced as a ‘guilty secret’ likened to a mistress that a physiologist could not give up but would not acknowledge in public. Biology’s ambivalent attitude toward teleological explanations persists in the twenty-first century.

Nineteenth-century final causes were ‘barren virgins’, an aphorism attributed to Francis Bacon, but twentieth-century teleology was a ‘mistress’, an adage of uncertain provenance. A study of historical uses of these gendered metaphors is used to probe changing attitudes toward teleological reasoning in biology. At the beginning of the nineteenth-century, invocations of final causes were commonplace but such idioms are rarely used at its end. This change is commonly attributed to publication of the Origin of Species in 1859 which completed the ejection of final causes from biology. Charles Darwin, however, openly and unashamedly uses teleological reasoning and language in his botanical research. He believed he had naturalized, rather than eliminated, the concept of final cause. A more important reason for the eclipse of final causes was the shift within physiology toward the explanatory modes of the physical sciences which had long held final causes in disrepute. The rejection of final causes as explanatory principles occurred despite a persistence of teleological reasoning that was experienced as a ‘guilty secret’ likened to a mistress that a physiologist could not give up but would not acknowledge in public. Biology’s ambivalent attitude toward teleological explanations persists in the twenty-first century. By the middle of the nineteenth century, such signs had become a familiar sight in many parts of Germany. In The Intercepted Love Letter, an 1850s painting by the Munich-based artist Carl Spitzweg, a young man is lowering a secret note from a garret window to his beloved sitting at the window one floor below. On the facade of the house, between the two floors, can be seen the fire mark of the Munich insurer Deutscher Phoenix, which bears a depiction of the mythical bird. Interestingly, the placing of the fire mark must have been a deliberate painterly choice, as such marks were never placed at such a height. Prominently displayed in this unusual location, the sign is perhaps intended to indicate to the viewer the social station of the young woman, who clearly comes from a good (Phoenix-insured) home. But it is also a risk-averse home, one that presumably would not encourage fiery love, love that shuns middle-class calculations about long-term security, financial and otherwise. It has been noted, however, that the pair of doves (read: lovebirds) to the right of the fire mark are presented slightly enlarged, perhaps an indication that, unlike fire, love finally cannot be extinguished. Whichever reading one subscribes to, Spitzweg’s painting figures the fate of love in the age of modern insurance, a history that has yet to be written.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, such signs had become a familiar sight in many parts of Germany. In The Intercepted Love Letter, an 1850s painting by the Munich-based artist Carl Spitzweg, a young man is lowering a secret note from a garret window to his beloved sitting at the window one floor below. On the facade of the house, between the two floors, can be seen the fire mark of the Munich insurer Deutscher Phoenix, which bears a depiction of the mythical bird. Interestingly, the placing of the fire mark must have been a deliberate painterly choice, as such marks were never placed at such a height. Prominently displayed in this unusual location, the sign is perhaps intended to indicate to the viewer the social station of the young woman, who clearly comes from a good (Phoenix-insured) home. But it is also a risk-averse home, one that presumably would not encourage fiery love, love that shuns middle-class calculations about long-term security, financial and otherwise. It has been noted, however, that the pair of doves (read: lovebirds) to the right of the fire mark are presented slightly enlarged, perhaps an indication that, unlike fire, love finally cannot be extinguished. Whichever reading one subscribes to, Spitzweg’s painting figures the fate of love in the age of modern insurance, a history that has yet to be written.

Y

Y I usually get up by 7 A.M. and am in bed by 10 P.M. I tend to eat meals at the same times of day, too. This may sound a little dull, but it’s essential for my productivity. It’s also a schedule that rarely disrupts my body clock. And a steady clock, it turns out, just might help me and many other people avoid cancer and some other diseases, according to new research.

I usually get up by 7 A.M. and am in bed by 10 P.M. I tend to eat meals at the same times of day, too. This may sound a little dull, but it’s essential for my productivity. It’s also a schedule that rarely disrupts my body clock. And a steady clock, it turns out, just might help me and many other people avoid cancer and some other diseases, according to new research.