David Adams at The Millions:

On the phone from his home in Princeton, N.J., on an unseasonably warm day in April, McPhee stresses that Tabula Rasa, which gathers the 92-year-old New Yorker writer’s reflections on projects he once contemplated but never wrote, is not an autobiography. It was, however, done according to Twain’s instructions for “how someone ought to do an autobiography—in a totally random miscellaneous way.” McPhee continues, “Twain’s point is just to jump in anywhere, anywhere at all, and start talking. And if something distracts you, if it seems more interesting, leave the first thing, and go to the second or the third. You can always go back to the first thing next week.”

On the phone from his home in Princeton, N.J., on an unseasonably warm day in April, McPhee stresses that Tabula Rasa, which gathers the 92-year-old New Yorker writer’s reflections on projects he once contemplated but never wrote, is not an autobiography. It was, however, done according to Twain’s instructions for “how someone ought to do an autobiography—in a totally random miscellaneous way.” McPhee continues, “Twain’s point is just to jump in anywhere, anywhere at all, and start talking. And if something distracts you, if it seems more interesting, leave the first thing, and go to the second or the third. You can always go back to the first thing next week.”

Legions of McPhee fans will need a moment to pick themselves up off the floor. Anyone who’s cracked the spine of 2017’s Draft No. 4, an immersive blend of writerly advice and career retrospective that sets down lessons McPhee has been teaching at Princeton University since the 1970s, will recall the intricate diagrams of his New Yorker essays, and the arduous process by which he arrived at their elegant structures.

More here.

In 1961, Federal Communications Commission chairman Newton N. Minow delivered a scathing assessment of the state of television to the National Association of Broadcasters, famously dubbing their collective output—from vapid and violent programing to the clamor of endless commercial breaks—a “vast wasteland.” Today, decades into the digital age, signs of this wasteland’s demise abound. Broadcast viewership has fallen by a third since 2015. Millions are pulling the plug on their cable subscriptions. Most adults under the age of thirty say they don’t watch TV. But is what Minow called “the television age” truly over? Or does the wasteland endure?

In 1961, Federal Communications Commission chairman Newton N. Minow delivered a scathing assessment of the state of television to the National Association of Broadcasters, famously dubbing their collective output—from vapid and violent programing to the clamor of endless commercial breaks—a “vast wasteland.” Today, decades into the digital age, signs of this wasteland’s demise abound. Broadcast viewership has fallen by a third since 2015. Millions are pulling the plug on their cable subscriptions. Most adults under the age of thirty say they don’t watch TV. But is what Minow called “the television age” truly over? Or does the wasteland endure? After you die, your body’s atoms will disperse and find new venues, making their way into oceans, trees and other bodies. But according to the laws of quantum mechanics, all of the information about your body’s build and function will prevail. The relations between the atoms, the uncountable particulars that made you you, will remain forever preserved, albeit in unrecognisably scrambled form – lost in practice, but immortal in principle.

After you die, your body’s atoms will disperse and find new venues, making their way into oceans, trees and other bodies. But according to the laws of quantum mechanics, all of the information about your body’s build and function will prevail. The relations between the atoms, the uncountable particulars that made you you, will remain forever preserved, albeit in unrecognisably scrambled form – lost in practice, but immortal in principle. It’s commonplace to note that sociopolitical upheaval and artistic experimentation often flourish side by side. But today — despite an alleged “polycrisis” — new modes of cultural production don’t seem to be emerging. Three years after the start of the Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent George Floyd rebellion, the arts seem stagnant and stubbornly centralized: franchise fare dominates at the box office; literary output is hampered by monopolized publishers; even the obsession with so-called nepo babies suggests a cultural bloodline without disruption. The internet, meanwhile, tends to both homogenize art and silo audiences by algorithm. We’ve begun to wonder if we’re overlooking experimental movements, or if they’re going extinct.

It’s commonplace to note that sociopolitical upheaval and artistic experimentation often flourish side by side. But today — despite an alleged “polycrisis” — new modes of cultural production don’t seem to be emerging. Three years after the start of the Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent George Floyd rebellion, the arts seem stagnant and stubbornly centralized: franchise fare dominates at the box office; literary output is hampered by monopolized publishers; even the obsession with so-called nepo babies suggests a cultural bloodline without disruption. The internet, meanwhile, tends to both homogenize art and silo audiences by algorithm. We’ve begun to wonder if we’re overlooking experimental movements, or if they’re going extinct. Let’s get this out of the way up front: Napoleon Bonaparte was not short. Most contemporary sources put him at about 5-foot-6,

Let’s get this out of the way up front: Napoleon Bonaparte was not short. Most contemporary sources put him at about 5-foot-6,  In 2017, a team of scientists from Germany trekked to Chile to investigate how living organisms sculpt the face of the Earth. A local ranger guided them through Pan de Azúcar, a roughly 150-square-mile national park on the southern coast of the Atacama Desert, which is often described as the driest place on Earth. They found themselves in a flat, gravelly wasteland interrupted by occasional hills, where hairy cacti reached their arms toward a sky that never rained. The ground under their feet formed a checkerboard, with irregular patches of dark pebbles sitting between lighter ones as bleached as bone.

In 2017, a team of scientists from Germany trekked to Chile to investigate how living organisms sculpt the face of the Earth. A local ranger guided them through Pan de Azúcar, a roughly 150-square-mile national park on the southern coast of the Atacama Desert, which is often described as the driest place on Earth. They found themselves in a flat, gravelly wasteland interrupted by occasional hills, where hairy cacti reached their arms toward a sky that never rained. The ground under their feet formed a checkerboard, with irregular patches of dark pebbles sitting between lighter ones as bleached as bone. Katherine Brading in Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews:

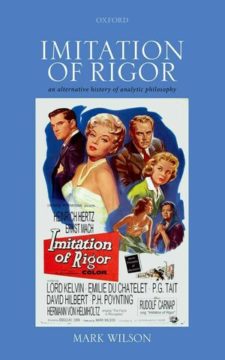

Katherine Brading in Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews: John Bellamy Foster in Monthly Review:

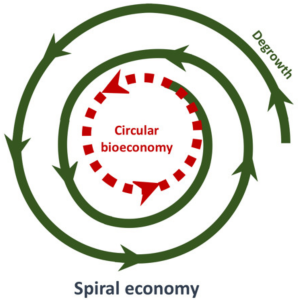

John Bellamy Foster in Monthly Review: Tony Wood in the LRB:

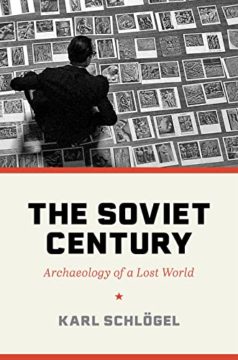

Tony Wood in the LRB: In 1867, shortly after Prussia’s decisive military victories over Denmark (in 1864) and Austria (in 1866), a dinner guest asked the Prussian prime minister, Otto von Bismarck, about the prospect of a further armed conflict, this time against France. Would it be expedient to somehow provoke a French attack on Prussia in order to unify the German states against a common enemy? Bismarck rejected the idea: ‘Anyone who has ever looked into the glazed eyes of a soldier dying on the battlefield will think hard before starting a war.’

In 1867, shortly after Prussia’s decisive military victories over Denmark (in 1864) and Austria (in 1866), a dinner guest asked the Prussian prime minister, Otto von Bismarck, about the prospect of a further armed conflict, this time against France. Would it be expedient to somehow provoke a French attack on Prussia in order to unify the German states against a common enemy? Bismarck rejected the idea: ‘Anyone who has ever looked into the glazed eyes of a soldier dying on the battlefield will think hard before starting a war.’ P

P Over the last five decades, we’ve burned enough coal, gas and oil, cut down enough trees, and produced enough other emissions to trap some six billion Hiroshima bombs’ worth of heat inside the climate system. Shockingly, though, only

Over the last five decades, we’ve burned enough coal, gas and oil, cut down enough trees, and produced enough other emissions to trap some six billion Hiroshima bombs’ worth of heat inside the climate system. Shockingly, though, only