Tobias Rose-Stockwell at Literary Hub:

For the first time, the majority of information we consume as a species is controlled by algorithms built to capture our emotional attention. As a result, we hear more angry voices shouting fearful opinions and we see more threats and frightening news simply because these are the stories most likely to engage us. This engagement is profitable for everyone involved: producers, journalists, creators, politicians, and, of course, the platforms themselves.

For the first time, the majority of information we consume as a species is controlled by algorithms built to capture our emotional attention. As a result, we hear more angry voices shouting fearful opinions and we see more threats and frightening news simply because these are the stories most likely to engage us. This engagement is profitable for everyone involved: producers, journalists, creators, politicians, and, of course, the platforms themselves.

The machinery of social media has become a lens through which society views itself—it is fundamentally changing the rules of human discourse. We’ve all learned to play this game with our own posts and content, earning our own payments in minute rushes of dopamine, and small metrics of acclaim. As a result, our words are suddenly soaked in righteousness, certainty, and extreme judgment.

More here.

The Earth’s atmosphere is good for some things, like providing something to breathe. But it does get in the way of astronomers, who have been successful at launching orbiting telescopes into space. But gravity and the ground are also useful for certain things, like walking around. The Moon, fortunately, provides gravity and a solid surface without any complications of a thick atmosphere — perfect for astronomical instruments. Building telescopes and other kinds of scientific instruments on the Moon is an expensive and risky endeavor, but the time may have finally arrived. I talk with astrophysicist Joseph Silk about the case for doing astronomy from the Moon, and what special challenges and opportunities are involved.

The Earth’s atmosphere is good for some things, like providing something to breathe. But it does get in the way of astronomers, who have been successful at launching orbiting telescopes into space. But gravity and the ground are also useful for certain things, like walking around. The Moon, fortunately, provides gravity and a solid surface without any complications of a thick atmosphere — perfect for astronomical instruments. Building telescopes and other kinds of scientific instruments on the Moon is an expensive and risky endeavor, but the time may have finally arrived. I talk with astrophysicist Joseph Silk about the case for doing astronomy from the Moon, and what special challenges and opportunities are involved. Imagine the entire cohort of U.S. graduating high school students this year as a group of one thousand bright-eyed 18-year-olds: kids of every class and race, spanning the whole spectrum of talent, wealth and oppression. What should the goal of progressive politics be for them? Where should attention be focused?

Imagine the entire cohort of U.S. graduating high school students this year as a group of one thousand bright-eyed 18-year-olds: kids of every class and race, spanning the whole spectrum of talent, wealth and oppression. What should the goal of progressive politics be for them? Where should attention be focused? O

O Things get especially interesting every weekend night about two and a half hours into the show, when Swift diverges from her otherwise precisely orchestrated set to perform two “surprise songs” from her catalog acoustically, never to be repeated at a later show, or so she says. The number of viewers in the live streams increase threefold, and fans on TikTok broadcast their feral reactions to Swift’s choices, which become ripe for close reading. “If I hear ‘friends break up’ I’m gonna kill myself,” one user watching the Cincinnati show

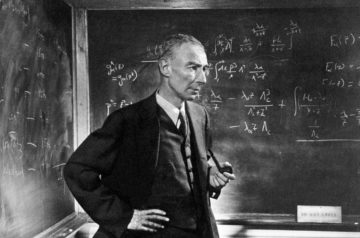

Things get especially interesting every weekend night about two and a half hours into the show, when Swift diverges from her otherwise precisely orchestrated set to perform two “surprise songs” from her catalog acoustically, never to be repeated at a later show, or so she says. The number of viewers in the live streams increase threefold, and fans on TikTok broadcast their feral reactions to Swift’s choices, which become ripe for close reading. “If I hear ‘friends break up’ I’m gonna kill myself,” one user watching the Cincinnati show  This week, the much anticipated movie Oppenheimer hits theaters, giving famed filmmaker Christopher Nolan’s take on the theoretical physicist who during World War II led the Manhattan Project to develop the first atomic bomb. J. Robert Oppenheimer, who died in 1967, is known as a charismatic leader, eloquent public intellectual, and Red Scare victim who in 1954 lost his security clearance in part because of his earlier associations with suspected Communists. To learn about Oppenheimer the scientist, Science spoke with David C. Cassidy, a physicist and historian emeritus at Hofstra University. Cassidy has authored or edited 10 books, including J. Robert Oppenheimer and the American Century.

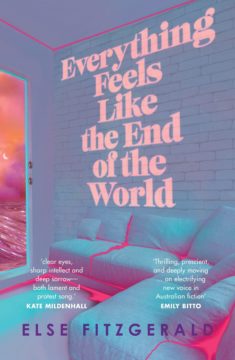

This week, the much anticipated movie Oppenheimer hits theaters, giving famed filmmaker Christopher Nolan’s take on the theoretical physicist who during World War II led the Manhattan Project to develop the first atomic bomb. J. Robert Oppenheimer, who died in 1967, is known as a charismatic leader, eloquent public intellectual, and Red Scare victim who in 1954 lost his security clearance in part because of his earlier associations with suspected Communists. To learn about Oppenheimer the scientist, Science spoke with David C. Cassidy, a physicist and historian emeritus at Hofstra University. Cassidy has authored or edited 10 books, including J. Robert Oppenheimer and the American Century. Climate anxiety is understood by psychologists to be a form of ‘practical’ anxiety as it is considered a rational response to the threat of climate change and can lead to constructive behaviours. At a Melbourne Writers Festival panel in 2022, Else Fitzgerald described her debut short story collection, Everything Feels Like the End of the World, as an attempt to work through her own climate grief, a sorrow that has its roots in the successive periods of drought and flooding she experienced growing up in East Gippsland. This, surely – writing a book – is the kind of ‘constructive behaviour’ the psychologists have in mind. But what of climate anxiety that clamps down, that debilitates and immobilises? The anxiety I feel in relation to the climate crisis leaves me swinging wildly between maniacal bouts of information gathering and long periods of psychic paralysis, during which I work equally hard to avoid any mention of climate change and its attendant calamities.

Climate anxiety is understood by psychologists to be a form of ‘practical’ anxiety as it is considered a rational response to the threat of climate change and can lead to constructive behaviours. At a Melbourne Writers Festival panel in 2022, Else Fitzgerald described her debut short story collection, Everything Feels Like the End of the World, as an attempt to work through her own climate grief, a sorrow that has its roots in the successive periods of drought and flooding she experienced growing up in East Gippsland. This, surely – writing a book – is the kind of ‘constructive behaviour’ the psychologists have in mind. But what of climate anxiety that clamps down, that debilitates and immobilises? The anxiety I feel in relation to the climate crisis leaves me swinging wildly between maniacal bouts of information gathering and long periods of psychic paralysis, during which I work equally hard to avoid any mention of climate change and its attendant calamities. A powerful storm system that hit the U.S. Northeast on July 9 and 10, 2023, dumped

A powerful storm system that hit the U.S. Northeast on July 9 and 10, 2023, dumped  Especially in northern cities, Blacks were boxed into lives of poverty, redlined into areas of concentrated poverty and further isolated when the federal government built interstate highways that separated them from their white neighbors. Their neighborhoods were patrolled by police departments who moved like occupying forces, with extreme prejudice and impunity. In these places — Los Angeles, New York, Newark, Detroit, and other cities — police brutality was a regular occurrence.

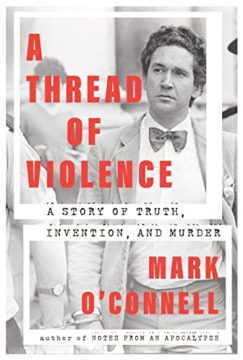

Especially in northern cities, Blacks were boxed into lives of poverty, redlined into areas of concentrated poverty and further isolated when the federal government built interstate highways that separated them from their white neighbors. Their neighborhoods were patrolled by police departments who moved like occupying forces, with extreme prejudice and impunity. In these places — Los Angeles, New York, Newark, Detroit, and other cities — police brutality was a regular occurrence. ‘And so it was that, on the evening of August 4, 1982,’ writes Mark O’Connell halfway through this gripping portrait of double killer Malcolm Macarthur, ‘the Irish government’s most senior legal official had his housekeeper prepare the spare room for his friend, a man who had just days previously murdered two strangers, and who had that very evening botched an armed robbery at the home of an acquaintance.’

‘And so it was that, on the evening of August 4, 1982,’ writes Mark O’Connell halfway through this gripping portrait of double killer Malcolm Macarthur, ‘the Irish government’s most senior legal official had his housekeeper prepare the spare room for his friend, a man who had just days previously murdered two strangers, and who had that very evening botched an armed robbery at the home of an acquaintance.’ Even in December 2019, when he announced his disease in a long, devil-may-care New Yorker essay, he did it with a dynamite lede: “Lung cancer, rampant. No surprise.” The diagnosis wasn’t the only startling thing about these sentences: Schjeldahl was writing about his personal life for once, and doing so in the same chiseled prose in which he described Giacometti’s bronzes and Manet’s oils. No matter what his subject happened to be, he treated it as an invitation to write beautifully.

Even in December 2019, when he announced his disease in a long, devil-may-care New Yorker essay, he did it with a dynamite lede: “Lung cancer, rampant. No surprise.” The diagnosis wasn’t the only startling thing about these sentences: Schjeldahl was writing about his personal life for once, and doing so in the same chiseled prose in which he described Giacometti’s bronzes and Manet’s oils. No matter what his subject happened to be, he treated it as an invitation to write beautifully.

I

I The scientists want the

The scientists want the