Leslie Jamison in The New Yorker:

My childhood Barbies were always in trouble. I was constantly giving them diagnoses of rare diseases, performing risky surgeries to cure them, or else kidnapping them—jamming them into the deepest reaches of my closet, without plastic food or plastic water, so they could be saved again, returned to their plastic doll-cakes and their slightly-too-small wooden home. (My mother had drawn her lines in the sand; we had no Dreamhouse.) My abusive behavior was nothing special. Most girls I know liked to mess their Barbies up; and when it comes to child’s play, crisis is hardly unusual. It’s a way to make sense of the thrills and terrors of autonomy, the problem of other people’s desires, the brute force of parental disapproval. But there was something about Barbie that especially demanded crisis: her perfection. That’s why Barbie needed to have a special kind of surgery; why she was dying; why she was in danger. She was too flawless, something had to be wrong. I treated Barbie the way a mother with Munchausen syndrome by proxy might treat her child: I wanted to heal her, but I also needed her sick. I wanted to become Barbie, and I wanted to destroy her. I wanted her perfection, but I also wanted to punish her for being more perfect than I’d ever be.

My childhood Barbies were always in trouble. I was constantly giving them diagnoses of rare diseases, performing risky surgeries to cure them, or else kidnapping them—jamming them into the deepest reaches of my closet, without plastic food or plastic water, so they could be saved again, returned to their plastic doll-cakes and their slightly-too-small wooden home. (My mother had drawn her lines in the sand; we had no Dreamhouse.) My abusive behavior was nothing special. Most girls I know liked to mess their Barbies up; and when it comes to child’s play, crisis is hardly unusual. It’s a way to make sense of the thrills and terrors of autonomy, the problem of other people’s desires, the brute force of parental disapproval. But there was something about Barbie that especially demanded crisis: her perfection. That’s why Barbie needed to have a special kind of surgery; why she was dying; why she was in danger. She was too flawless, something had to be wrong. I treated Barbie the way a mother with Munchausen syndrome by proxy might treat her child: I wanted to heal her, but I also needed her sick. I wanted to become Barbie, and I wanted to destroy her. I wanted her perfection, but I also wanted to punish her for being more perfect than I’d ever be.

It’s not that I literally wanted to become her, of course—to wake up with a pair of hard plastic tits, coarse blond hair, waxy holes in my feet betraying the robotic fingerprint of my factory birthplace—but some part of me was already chasing the false gods she spoke for: beauty as a kind of spiritual guarantor, writing blank checks for my destiny; the self-effacing ease afforded by wealth and whiteness; selfhood as triumphant brand consistency, the erasure of opacity and self-destructive tendency. I craved all of these—still do, sometimes—even as my own awareness of their impossibility makes me want to destroy their false prophet: Barbie as snake-oil saleswoman hawking the existential and plasticine wares of her impossible femininity, one Pepto-Bismol-pink pet shop at a time.

More here.

It has been a hundred years since D.H. Lawrence published “Studies in Classic American Literature,” and in the annals of literary criticism the book may still claim the widest discrepancy between title and content.

It has been a hundred years since D.H. Lawrence published “Studies in Classic American Literature,” and in the annals of literary criticism the book may still claim the widest discrepancy between title and content. It’s 1965. Truman Capote was a known figure on the literary scene and a member of the global social jet set. His bestselling books Other Voices, Other Rooms and Breakfast at Tiffany’s had made him a literary favorite. And after five years of painstaking research, and gut-wrenching personal investment, part I of In Cold Blood debuted in The New Yorker. As people across the country opened their magazines and read the first lines of the story, they were riveted. Overnight, Capote catapulted from a mere darling of the literary world to a full-fledged global celebrity on a par with the likes of rockstars and film legends.

It’s 1965. Truman Capote was a known figure on the literary scene and a member of the global social jet set. His bestselling books Other Voices, Other Rooms and Breakfast at Tiffany’s had made him a literary favorite. And after five years of painstaking research, and gut-wrenching personal investment, part I of In Cold Blood debuted in The New Yorker. As people across the country opened their magazines and read the first lines of the story, they were riveted. Overnight, Capote catapulted from a mere darling of the literary world to a full-fledged global celebrity on a par with the likes of rockstars and film legends. Mainframe computers are often seen as ancient machines—practically dinosaurs. But mainframes, which are purpose-built to process enormous amounts of data, are still extremely relevant today. If they’re dinosaurs, they’re T-Rexes, and desktops and server computers are puny mammals to be trodden underfoot.

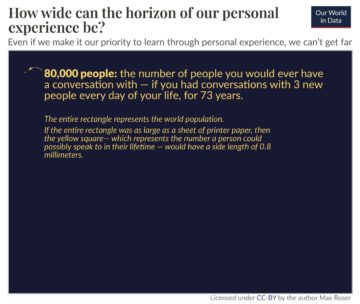

Mainframe computers are often seen as ancient machines—practically dinosaurs. But mainframes, which are purpose-built to process enormous amounts of data, are still extremely relevant today. If they’re dinosaurs, they’re T-Rexes, and desktops and server computers are puny mammals to be trodden underfoot. It’s tempting to believe that we can simply rely on personal experience to develop our understanding of the world. But that’s a mistake. The world is large, and we can experience only very little of it personally. To see what the world is like, we need to rely on other means: carefully-collected global statistics.

It’s tempting to believe that we can simply rely on personal experience to develop our understanding of the world. But that’s a mistake. The world is large, and we can experience only very little of it personally. To see what the world is like, we need to rely on other means: carefully-collected global statistics. When I finally did leave the sex trade after finishing my bachelor’s degree as a mature student, I spent seven years working in “good” jobs in the corporate sector. This meant, as I understood it, that I didn’t work nights, that I was a salaried employee, and that I had dental benefits. I had a shiny access card that opened doors—to a gleaming, marble elevator bank, to planters full of plastic ferns, to blocks of cubicles illuminated by fluorescent lighting, a land of perpetual daytime.

When I finally did leave the sex trade after finishing my bachelor’s degree as a mature student, I spent seven years working in “good” jobs in the corporate sector. This meant, as I understood it, that I didn’t work nights, that I was a salaried employee, and that I had dental benefits. I had a shiny access card that opened doors—to a gleaming, marble elevator bank, to planters full of plastic ferns, to blocks of cubicles illuminated by fluorescent lighting, a land of perpetual daytime. She was not beautiful, but she looked like she was. She was practically famous for it in the cloistered social universe of the liberal arts college where I had just arrived. Women whispered about her effortless elegance in the bathrooms at parties, and a man who had dated her for a summer informed me, with the dispassionate assurance of a connoisseur, that she was the hottest girl on campus. The skier who brazenly dozed in Introduction to Philosophy each morning intimated between snores that she looked like Uma Thurman, whom she did not resemble in the least. I knew this even though I had yet to see her for myself, because I had done what anyone with an appetite for truth and beauty would do in 2011, besides enroll in Introduction to Philosophy: I had studied her profile on Facebook—and discovered, much to my surprise and chagrin, an entirely average-looking person, slightly hunched, with a mop of mousy hair.

She was not beautiful, but she looked like she was. She was practically famous for it in the cloistered social universe of the liberal arts college where I had just arrived. Women whispered about her effortless elegance in the bathrooms at parties, and a man who had dated her for a summer informed me, with the dispassionate assurance of a connoisseur, that she was the hottest girl on campus. The skier who brazenly dozed in Introduction to Philosophy each morning intimated between snores that she looked like Uma Thurman, whom she did not resemble in the least. I knew this even though I had yet to see her for myself, because I had done what anyone with an appetite for truth and beauty would do in 2011, besides enroll in Introduction to Philosophy: I had studied her profile on Facebook—and discovered, much to my surprise and chagrin, an entirely average-looking person, slightly hunched, with a mop of mousy hair. Scientists have come to realize that in the soil and rocks beneath our feet there lies

Scientists have come to realize that in the soil and rocks beneath our feet there lies  Last week, Sinéad O’Connor took off on an early-morning bicycle trip around Wilmette, Illinois, a pleasant suburb of Chicago. The Irish pop singer—now forty-nine, and still best known for ripping up a photograph of Pope John Paul II on “Saturday Night Live,” in 1992, while singing the word “evil,” a remonstrance against the Vatican’s handling of sexual-abuse allegations—had previously expressed suicidal ideations, and, in 2012, admitted to a “very serious breakdown,” which led her to cancel a world tour. Ergo, when she still hadn’t returned from her bike ride twenty-four hours later, the police helicopters began circling. Details regarding what happened next—precisely where O’Connor was found, and in what condition—have been scant, but authorities confirmed her safety by the end of the day.

Last week, Sinéad O’Connor took off on an early-morning bicycle trip around Wilmette, Illinois, a pleasant suburb of Chicago. The Irish pop singer—now forty-nine, and still best known for ripping up a photograph of Pope John Paul II on “Saturday Night Live,” in 1992, while singing the word “evil,” a remonstrance against the Vatican’s handling of sexual-abuse allegations—had previously expressed suicidal ideations, and, in 2012, admitted to a “very serious breakdown,” which led her to cancel a world tour. Ergo, when she still hadn’t returned from her bike ride twenty-four hours later, the police helicopters began circling. Details regarding what happened next—precisely where O’Connor was found, and in what condition—have been scant, but authorities confirmed her safety by the end of the day. Behind cardiovascular disease, cancer is the second major cause of death in the United States and will likely cause

Behind cardiovascular disease, cancer is the second major cause of death in the United States and will likely cause  Even before Lee Iacocca sold the two-millionth copy of his autobiography, it was the most successful business book of its kind. More impressively, when that sales milestone was reached in July 1985, less than a year after its publication, Iacocca joined the ranks of America’s all-time bestsellers, regardless of genre, including Gone With the Wind and The Power of Positive Thinking. From his humble origins as the firstborn son of Italian immigrants, Iacocca distinguished himself as an engineer at Ford Motor Company before becoming CEO of the Chrysler Corporation in 1978, when it was on the brink of bankruptcy. Iacocca turned Chrysler around, paying back a government bailout and leading the former automotive straggler to the top of the car industry within a few short years. Highlighted repeatedly in Iacocca’s practically unavoidable TV commercials for Chrysler in the 1980s and ’90s, it was an American success story. But it was also something else, maybe something more: the creation of a new character on the American scene, the Celebrity CEO.

Even before Lee Iacocca sold the two-millionth copy of his autobiography, it was the most successful business book of its kind. More impressively, when that sales milestone was reached in July 1985, less than a year after its publication, Iacocca joined the ranks of America’s all-time bestsellers, regardless of genre, including Gone With the Wind and The Power of Positive Thinking. From his humble origins as the firstborn son of Italian immigrants, Iacocca distinguished himself as an engineer at Ford Motor Company before becoming CEO of the Chrysler Corporation in 1978, when it was on the brink of bankruptcy. Iacocca turned Chrysler around, paying back a government bailout and leading the former automotive straggler to the top of the car industry within a few short years. Highlighted repeatedly in Iacocca’s practically unavoidable TV commercials for Chrysler in the 1980s and ’90s, it was an American success story. But it was also something else, maybe something more: the creation of a new character on the American scene, the Celebrity CEO. A study of more than 38,000 young people has confirmed what researchers had begun to suspect: the COVID-19 pandemic precipitated a jump in cases of type 1 diabetes in children and teenagers. At first, researchers thought that the rise was caused by the virus itself — but it turns out that is probably not true. Nevertheless, with the overall cause of type 1 diabetes still a mystery, the findings offer new mechanisms for researchers to explore.

A study of more than 38,000 young people has confirmed what researchers had begun to suspect: the COVID-19 pandemic precipitated a jump in cases of type 1 diabetes in children and teenagers. At first, researchers thought that the rise was caused by the virus itself — but it turns out that is probably not true. Nevertheless, with the overall cause of type 1 diabetes still a mystery, the findings offer new mechanisms for researchers to explore. Narendra Modi, the 72-year-old Hindu activist from Gujarat, has been prime minister since 2014. His father was a railroad station tea seller. A rare member of India’s “backward” castes to reach his country’s top post, he is the antitype of the urbane Nehru, and the movement he leads is the antithesis of Congress as Nehru reshaped it. Under Modi’s leadership the BJP, founded in 1980 and focused on the aspirations of the 80% of Indians who are Hindu, has become the world’s largest political party. Political scientists say India has moved on to a “second party system” with the BJP at its center, much as the first party system was dominated by Congress.

Narendra Modi, the 72-year-old Hindu activist from Gujarat, has been prime minister since 2014. His father was a railroad station tea seller. A rare member of India’s “backward” castes to reach his country’s top post, he is the antitype of the urbane Nehru, and the movement he leads is the antithesis of Congress as Nehru reshaped it. Under Modi’s leadership the BJP, founded in 1980 and focused on the aspirations of the 80% of Indians who are Hindu, has become the world’s largest political party. Political scientists say India has moved on to a “second party system” with the BJP at its center, much as the first party system was dominated by Congress. The critical tide is turning, once again. The professional critics—and not just the old, curmudgeonly ones—are fed up with moralizing, and they are willing to speak about it in public. From Lauren Oyler’s observation that “anxieties about being a good person, surrounded by good people, pervade contemporary novels and criticism” to Parul Sehgal’s exhortation against the ubiquitous “trauma plot” that “flattens, distorts, reduces character to symptom, and … insists upon its moral authority” to Garth Greenwell’s lament about a literary culture that “is as moralistic as it has ever been in my lifetime”—the critical vanguard has made its judgment clear. For all its good intentions, art that tries to minister to its audience by showcasing moral aspirants and paragons or the abject victims of political oppression produces smug, tiresome works that are failures both as art and as agitprop. Artists and critics—their laurel bearers—should take heed.

The critical tide is turning, once again. The professional critics—and not just the old, curmudgeonly ones—are fed up with moralizing, and they are willing to speak about it in public. From Lauren Oyler’s observation that “anxieties about being a good person, surrounded by good people, pervade contemporary novels and criticism” to Parul Sehgal’s exhortation against the ubiquitous “trauma plot” that “flattens, distorts, reduces character to symptom, and … insists upon its moral authority” to Garth Greenwell’s lament about a literary culture that “is as moralistic as it has ever been in my lifetime”—the critical vanguard has made its judgment clear. For all its good intentions, art that tries to minister to its audience by showcasing moral aspirants and paragons or the abject victims of political oppression produces smug, tiresome works that are failures both as art and as agitprop. Artists and critics—their laurel bearers—should take heed.