Gaby Hinsliff in The Guardian:

It must be a while ago now since Chris Bryant has had to write a sermon. But the former curate turned Labour MP, middle-ranking minister and latterly chair of the parliamentary committee that helps determine the fate of MPs who have sinned, doesn’t seem to have lost the knack. His account of what is rotten in the state of politics is neither lofty – if anything Bryant goes out of his way to confess to what he sees as his own failings, including a tendency to be “impulsive, sanctimonious and pompous” – nor overmoralising, but remains gently steadfast in the belief that parliament in general and this one in particular has lost its way. Code of Conduct is an attempt to guide it back to something like the straight and narrow.

It must be a while ago now since Chris Bryant has had to write a sermon. But the former curate turned Labour MP, middle-ranking minister and latterly chair of the parliamentary committee that helps determine the fate of MPs who have sinned, doesn’t seem to have lost the knack. His account of what is rotten in the state of politics is neither lofty – if anything Bryant goes out of his way to confess to what he sees as his own failings, including a tendency to be “impulsive, sanctimonious and pompous” – nor overmoralising, but remains gently steadfast in the belief that parliament in general and this one in particular has lost its way. Code of Conduct is an attempt to guide it back to something like the straight and narrow.

He is, of course, entering a crowded literary field. Almost half the publishing industry seems to have had a shot now at detailing how the Boris Johnson era descended into such squalor; the lies, the chaos, the unedifying scrabble around for someone else to pay for his interior designers, and the willingness to overlook all manner of dubious behaviour in his ministers and aides. Even more ink has been spilt on the way Brexit has twisted politics out of shape, with its litany of false promises setting up leave voters for inevitable disillusionment. The queasy charade that is the modern honours system or the culture of abuse and threats that puts good people off standing for parliament are equally well-worn subjects, and in that sense Bryant is comparatively late to the party. But he brings with him more than two decades’ experience as a parliamentarian, a nonpartisan approach that helps him look beyond the failings of individuals to the system itself, and a raft of often small but practical suggestions for cleaning out the stables.

More here.

Stanford University scientists have invented a new kind of paint that can keep homes and other buildings cooler in the summer and warmer in the winter, significantly reducing energy use, costs, and greenhouse gas emissions.

Stanford University scientists have invented a new kind of paint that can keep homes and other buildings cooler in the summer and warmer in the winter, significantly reducing energy use, costs, and greenhouse gas emissions. L

L W

W On the one hand, the promise of a liberal society is of a society of equals – of people who are equally entitled and empowered to make decisions about their own lives, and who are equal participants in the collective governance of that society. Liberalism professes to achieve this by protecting liberties. Some of these are personal liberties. I get to decide how to style my hair, which religion to profess, what I say or don’t say, which groups I join, and what I do with my own property. Some of these liberties are political: I should have the same chance as anyone else to influence the direction of our society and government by voting, joining political parties, marching and demonstrating, standing for office, writing op-eds, or organising support for causes or candidates.

On the one hand, the promise of a liberal society is of a society of equals – of people who are equally entitled and empowered to make decisions about their own lives, and who are equal participants in the collective governance of that society. Liberalism professes to achieve this by protecting liberties. Some of these are personal liberties. I get to decide how to style my hair, which religion to profess, what I say or don’t say, which groups I join, and what I do with my own property. Some of these liberties are political: I should have the same chance as anyone else to influence the direction of our society and government by voting, joining political parties, marching and demonstrating, standing for office, writing op-eds, or organising support for causes or candidates. Driverless cars have the green light to operate as paid ride-hailing services in San Francisco after the companies Waymo and Cruise won approval from California state regulators. But the decision comes amidst pushback from city officials and residents over the cars creating traffic jams and interfering with the work of firefighters and police officers.

Driverless cars have the green light to operate as paid ride-hailing services in San Francisco after the companies Waymo and Cruise won approval from California state regulators. But the decision comes amidst pushback from city officials and residents over the cars creating traffic jams and interfering with the work of firefighters and police officers. The Bible is a foundational text in Western literature, ignored at an aspiring writer’s hazard, and when I was younger I had the ambition to read it cover to cover. After breezing through the early stories and slogging through the religious laws, which were at least of sociological interest, I chose to cut myself some slack with Kings and Chronicles, whose lists of patriarchs and their many sons seemed no more necessary to read than a phonebook. With judicious skimming, I made it to the end of Job. But then came the Psalms, and there my ambition foundered. Although a few of the Psalms are memorable (“The Lord is my shepherd”), in the main they’re incredibly repetitive. Again and again the refrain: Life is challenging but God is good. To enjoy the Psalms, to appreciate the nuances of devotion they register, you had to be a believer. You had to love God, which I didn’t. And so I set the book aside.

The Bible is a foundational text in Western literature, ignored at an aspiring writer’s hazard, and when I was younger I had the ambition to read it cover to cover. After breezing through the early stories and slogging through the religious laws, which were at least of sociological interest, I chose to cut myself some slack with Kings and Chronicles, whose lists of patriarchs and their many sons seemed no more necessary to read than a phonebook. With judicious skimming, I made it to the end of Job. But then came the Psalms, and there my ambition foundered. Although a few of the Psalms are memorable (“The Lord is my shepherd”), in the main they’re incredibly repetitive. Again and again the refrain: Life is challenging but God is good. To enjoy the Psalms, to appreciate the nuances of devotion they register, you had to be a believer. You had to love God, which I didn’t. And so I set the book aside. After a retired speech-language pathologist had a stroke,

After a retired speech-language pathologist had a stroke, Dan Hitchens in Compact Magazine:

Dan Hitchens in Compact Magazine: Allison Parshall in Quanta:

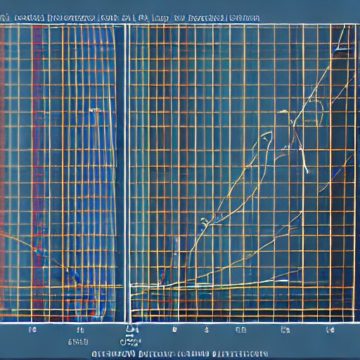

Allison Parshall in Quanta: Daron Acemoglu, Gary Anderson, David Beede, Catherine Buffington, et. al., in VoxEU:

Daron Acemoglu, Gary Anderson, David Beede, Catherine Buffington, et. al., in VoxEU: O

O Has any man in history loved anything as much as Orson Squire Fowler loved the octagon? Fowler, born in Cohocton, N.Y., in 1809, published a book in 1848 arguing that all houses should be eight-sided. He influenced a (failed) utopian community in Kansas called Octagon City, delivered an estimated 350 public orations on octagon supremacy and built himself a 60-room octagonal palace in upstate New York.

Has any man in history loved anything as much as Orson Squire Fowler loved the octagon? Fowler, born in Cohocton, N.Y., in 1809, published a book in 1848 arguing that all houses should be eight-sided. He influenced a (failed) utopian community in Kansas called Octagon City, delivered an estimated 350 public orations on octagon supremacy and built himself a 60-room octagonal palace in upstate New York.