Nathan Sperber in Sidecar:

Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman does not mince his words:

the signs are now unmistakable: China is in big trouble. We’re not talking about some minor setback along the way, but something more fundamental. The country’s whole way of doing business, the economic system that has driven three decades of incredible growth, has reached its limits. You could say that the Chinese model is about to hit its Great Wall, and the only question now is just how bad the crash will be.

That was in the summer of 2013. China’s GDP grew by 7.8 per cent that year. In the decade since, its economy has expanded by 70 per cent in real terms, compared to 21 per cent for the United States. China has not had a recession this century – by convention, two consecutive quarters of negative growth – let alone a ‘crash’. Yet every few years, the Anglophone financial media and its trail of investors, analysts and think-tankers are gripped by the belief that the Chinese economy is about to crater.

The conviction reared its head in the early 2000s, when runaway investment was thought to be ‘overheating’ the economy; in the late 2000s, when exports contracted in the wake of the global financial crisis; and in the mid-2010s, when it was feared that a buildup of local government debt, under-regulated shadow banking and capital outflows threatened China’s entire economic edifice. Today, dire predictions are out in force again, this time triggered by underwhelming growth figures for the second quarter of 2023. Exports have declined from the heights they reached during the pandemic while consumer spending has softened. Corporate troubles in the property sector and high youth unemployment appear to add to China’s woes. Against this backdrop, Western commentators are casting doubt on the PRC’s ability to continue to churn out GDP units, or fretting in grander terms about the country’s economic future (‘whither China?’, asks Adam Tooze by way of Yang Xiguang).

More here.

On 22 February1946, George Kennan, an American diplomat stationed in Moscow, dictated a 5,000-word cable to Washington. In this famous telegram, Kennan warned that the Soviet Union’s commitment to communism meant that it was inherently expansionist, and urged the US government to resist any attempts by the Soviets to increase their influence. This strategy quickly became known as “containment” – and defined American foreign policy for the next 40 years.

On 22 February1946, George Kennan, an American diplomat stationed in Moscow, dictated a 5,000-word cable to Washington. In this famous telegram, Kennan warned that the Soviet Union’s commitment to communism meant that it was inherently expansionist, and urged the US government to resist any attempts by the Soviets to increase their influence. This strategy quickly became known as “containment” – and defined American foreign policy for the next 40 years. For Julian Huxley, science was spiritual. The biologist, brother of the novelist Aldous Huxley and grandson of “Darwin’s Bulldog”

For Julian Huxley, science was spiritual. The biologist, brother of the novelist Aldous Huxley and grandson of “Darwin’s Bulldog”  Writing is a solitary practice;

Writing is a solitary practice; Quantum computers have long promised to solve certain problems faster than any ordinary, or classical, computer can. In fact, Google delivered on this promise in 2019, when it

Quantum computers have long promised to solve certain problems faster than any ordinary, or classical, computer can. In fact, Google delivered on this promise in 2019, when it  In November, the United Kingdom will host a high-profile international summit on the governance of artificial intelligence. With the agenda and list of invitees still being finalized, the biggest decision facing UK officials is whether to invite China or host a more exclusive gathering for the G7 and other countries that want to safeguard liberal democracy as the foundation for a digital society.

In November, the United Kingdom will host a high-profile international summit on the governance of artificial intelligence. With the agenda and list of invitees still being finalized, the biggest decision facing UK officials is whether to invite China or host a more exclusive gathering for the G7 and other countries that want to safeguard liberal democracy as the foundation for a digital society. On a 95-degree evening in Austin last fall, I ran into a curator from the University of Texas’ Blanton Museum of Art at a gallery reception across town. We briefly chatted about the Blanton’s then recently opened “Ellsworth Kelly: Postcards” exhibition, which had been organized by the Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College. I mentioned I was covering the show for Salmagundi and that I was very much looking forward to seeing the presentation—a departure from the artist’s much larger monochromatic works—up close and personal, and possibly with a pair of reading glasses.

On a 95-degree evening in Austin last fall, I ran into a curator from the University of Texas’ Blanton Museum of Art at a gallery reception across town. We briefly chatted about the Blanton’s then recently opened “Ellsworth Kelly: Postcards” exhibition, which had been organized by the Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College. I mentioned I was covering the show for Salmagundi and that I was very much looking forward to seeing the presentation—a departure from the artist’s much larger monochromatic works—up close and personal, and possibly with a pair of reading glasses. Not so long ago, India’s greatest export to the West, people aside, was spirituality. Mick Brown’s The Nirvana Express is an engaging history of India’s spiritual influence on the West between 1893, when Swami Vivekananda was the surprise star at the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago, and 1990, when the multimillionaire cult leader and tax dodger Bhagwan Rajneesh popped his sandals. The economic reforms that began the transformation of India’s economy started a year after Rajneesh’s death. The subsequent changes make the history described in Nirvana Express feel almost ancient.

Not so long ago, India’s greatest export to the West, people aside, was spirituality. Mick Brown’s The Nirvana Express is an engaging history of India’s spiritual influence on the West between 1893, when Swami Vivekananda was the surprise star at the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago, and 1990, when the multimillionaire cult leader and tax dodger Bhagwan Rajneesh popped his sandals. The economic reforms that began the transformation of India’s economy started a year after Rajneesh’s death. The subsequent changes make the history described in Nirvana Express feel almost ancient. FRANZ KAFKA’S LAST STORYwas a fable about art and labor. “Josephine the Singer, or the Mouse Folk” is a tale told by a mouse who, with marked erudition and fair-mindedness, reflects on an extraordinary community member, the singer Josephine. At times of danger or emergency, the news will spread that she plans to sing. The community assembles, and Josephine, delicate and frail, stands before them in song, her arms spread wide, her throat stretched high. The tones emanating from that delicate throat are, according to some, not singing at all but rather ordinary piping—if anything, weaker and thinner than the sounds all mice make. It is peculiar, the narrator considers, that “here is someone making a ceremonial performance out of doing the usual thing.” But her art has a strange hold on all who listen. It turns the ordinary materials of speech into something transcendent.

FRANZ KAFKA’S LAST STORYwas a fable about art and labor. “Josephine the Singer, or the Mouse Folk” is a tale told by a mouse who, with marked erudition and fair-mindedness, reflects on an extraordinary community member, the singer Josephine. At times of danger or emergency, the news will spread that she plans to sing. The community assembles, and Josephine, delicate and frail, stands before them in song, her arms spread wide, her throat stretched high. The tones emanating from that delicate throat are, according to some, not singing at all but rather ordinary piping—if anything, weaker and thinner than the sounds all mice make. It is peculiar, the narrator considers, that “here is someone making a ceremonial performance out of doing the usual thing.” But her art has a strange hold on all who listen. It turns the ordinary materials of speech into something transcendent. Pakistan has introduced measures against modern slavery with mixed success. Climate change, however, is reinforcing the most egregious abuses due to mounting personal debt, and the economic relationship between sharecroppers and small farmers on the one hand, and landlords and local merchants on the other.

Pakistan has introduced measures against modern slavery with mixed success. Climate change, however, is reinforcing the most egregious abuses due to mounting personal debt, and the economic relationship between sharecroppers and small farmers on the one hand, and landlords and local merchants on the other. Ruscha’s avant-garde proclivities surfaced in his first pagework as a member of the group Students Five, a collective of friends—Joe Good, Jerry McMillan (both high-school classmates of Ruscha’s), Patrick Blackwell, Don Moore, and later Wall Batterton. Their mailer/bulletin, Orb,9 published in seven issues between 1959 and 1960 by Chouinard’s Society of Graphic Designers, contained an amalgam of cartoons, collages, graphic experiments, texts, and exhibition announcements. Ruscha edited and laid out the issues on a single seventeen-by-twenty-two-inch sheet, printing it recto-verso in an elaborate overlapping two-color system and folding it six times down for dissemination through the mail. Commenting on the genesis of Orb’s design, Ruscha would say, “I pasted the thing up and I maybe was thinking in the back of my head, Dada, ’cause they kind of echo a lot of the things that the Dadaists were doing. Things can be upside down, they don’t have to be orderly, you don’t have to have a proper well-behaved page line.”

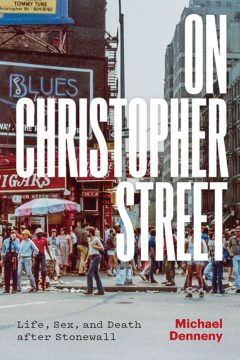

Ruscha’s avant-garde proclivities surfaced in his first pagework as a member of the group Students Five, a collective of friends—Joe Good, Jerry McMillan (both high-school classmates of Ruscha’s), Patrick Blackwell, Don Moore, and later Wall Batterton. Their mailer/bulletin, Orb,9 published in seven issues between 1959 and 1960 by Chouinard’s Society of Graphic Designers, contained an amalgam of cartoons, collages, graphic experiments, texts, and exhibition announcements. Ruscha edited and laid out the issues on a single seventeen-by-twenty-two-inch sheet, printing it recto-verso in an elaborate overlapping two-color system and folding it six times down for dissemination through the mail. Commenting on the genesis of Orb’s design, Ruscha would say, “I pasted the thing up and I maybe was thinking in the back of my head, Dada, ’cause they kind of echo a lot of the things that the Dadaists were doing. Things can be upside down, they don’t have to be orderly, you don’t have to have a proper well-behaved page line.” What distinguished the relationship between Gefter and Marks—other than the fact that it had lasted an eternity in gay years—was the photography. Inspired by the breathtaking tenderness of Alfred Stieglitz’s portraits of Georgia O’Keeffe, and Emmet Gowin’s of Edith Morris, Gefter, who had recently completed a BFA in photography and painting at the Pratt Institute, set out to document his romance with Marks, who, in turn, always insisted on reciprocating the photographic act. An archive of portraits, spontaneously taken by one another in moments of affection, lust, anxiety, jealousy, and fury, is the point of departure for their dialogues with Denneny. In his 2023 book On Christopher Street: Life, Sex, and Death after Stonewall, Denneny, who died this past April, described his aspiration to “make something like a literary or intellectual version of a Joseph Cornell box, using Philip and Neil’s photographs, the live interviews, and the written self-portraits to capture something—love, passion, and its loss—that I was obsessed with.”

What distinguished the relationship between Gefter and Marks—other than the fact that it had lasted an eternity in gay years—was the photography. Inspired by the breathtaking tenderness of Alfred Stieglitz’s portraits of Georgia O’Keeffe, and Emmet Gowin’s of Edith Morris, Gefter, who had recently completed a BFA in photography and painting at the Pratt Institute, set out to document his romance with Marks, who, in turn, always insisted on reciprocating the photographic act. An archive of portraits, spontaneously taken by one another in moments of affection, lust, anxiety, jealousy, and fury, is the point of departure for their dialogues with Denneny. In his 2023 book On Christopher Street: Life, Sex, and Death after Stonewall, Denneny, who died this past April, described his aspiration to “make something like a literary or intellectual version of a Joseph Cornell box, using Philip and Neil’s photographs, the live interviews, and the written self-portraits to capture something—love, passion, and its loss—that I was obsessed with.” The cells of all living organisms are powered by the same chemical fuel:

The cells of all living organisms are powered by the same chemical fuel: