Laura Marsh in The New Republic:

Laura Marsh in The New Republic:

Torching your own reputation is usually a onetime engagement. Credibility is finite, and once it’s gone, there is not much left to burn. A reporter who got their sources mixed up once will surprise no one next time they bungle a story; a writer who spreads conspiracy theories is soon known as a crank.

Those rules have somehow not held true for the writer Naomi Wolf. A notable feature of her career has been her ability to repeat the act of self-immolation over and over, singeing others along the way. In the first year of the pandemic, Wolf reliably drew fresh surprise and dismay when she made outlandish claims about the tyranny of public health measures and the dangers of vaccines. Each time that she declared, usually via Twitter, that Anthony Fauci was Satan, or that children who wore masks had lost the ability to smile, that the vaccines were a “software platform that can receive uploads,” or that she had uncovered a plot by Apple “to deliver vaccines [with] nanopatticles [sic] that let you travel back in time,” ripples of consternation followed. Was this really the same Naomi Wolf, the author of a widely read feminist treatise, The Beauty Myth; a longtime contributor to the liberal newspaper The Guardian; a familiar face on MSNBC—a fixture in liberal media since the 1990s? What had happened to her?

These questions proved remarkably durable. The latest Naomi Wolf development was a frequent spectacle on Twitter, and the subject of a steady drip of think pieces. “A Modern Feminist Classic Changed My Life. Was it Actually Garbage?” Rebecca Onion asked of The Beauty Myth in Slate, in March 2021. A few months later, Business Insider documented “Naomi Wolf’s Slide from Feminist, Democratic Party Icon to the ‘Conspiracist Whirlpool,’” and this magazine contemplated “The Madness of Naomi Wolf” in June that year, after Twitter suspended her account.

More here.

W

W The insurrection failed. The system held — at least for a time. In November 1923, when a young demagogue named Adolf Hitler tried to start a Nazi revolution from a Munich beer hall, his attempted coup was so disorganized that it swiftly degenerated into bumbling confusion. One participant later testified that the operation was such a farce that he whispered to others, “Play along with this comedy.”

The insurrection failed. The system held — at least for a time. In November 1923, when a young demagogue named Adolf Hitler tried to start a Nazi revolution from a Munich beer hall, his attempted coup was so disorganized that it swiftly degenerated into bumbling confusion. One participant later testified that the operation was such a farce that he whispered to others, “Play along with this comedy.” The health service is a contradiction. It has been built on immigrant labour from conception to the present day. Walk into many NHS services, and you will find it is Black and Brown faces that are assessing, diagnosing and treating. Yet we find huge race-based health disparities, in maternity, mental health, Covid-19 deaths and more.

The health service is a contradiction. It has been built on immigrant labour from conception to the present day. Walk into many NHS services, and you will find it is Black and Brown faces that are assessing, diagnosing and treating. Yet we find huge race-based health disparities, in maternity, mental health, Covid-19 deaths and more. The first time I heard about the

The first time I heard about the  C

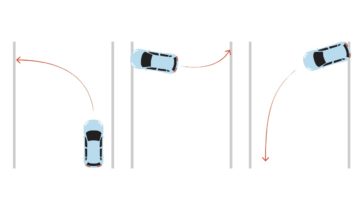

C There’s a fun math problem here about how much space you need to turn your car around, and mathematicians have been working on an idealized version of it for over 100 years. It started in 1917 when the Japanese mathematician Sōichi Kakeya posed a problem that sounds a little like our traffic jam. Suppose you’ve got an infinitely thin needle of length 1. What’s the area of the smallest region in which you can turn the needle 180 degrees and return it to its original position? This is known as Kakeya’s needle problem, and mathematicians are still studying variations of it. Let’s take a look at the simple geometry that makes Kakeya’s needle problem so interesting and surprising.

There’s a fun math problem here about how much space you need to turn your car around, and mathematicians have been working on an idealized version of it for over 100 years. It started in 1917 when the Japanese mathematician Sōichi Kakeya posed a problem that sounds a little like our traffic jam. Suppose you’ve got an infinitely thin needle of length 1. What’s the area of the smallest region in which you can turn the needle 180 degrees and return it to its original position? This is known as Kakeya’s needle problem, and mathematicians are still studying variations of it. Let’s take a look at the simple geometry that makes Kakeya’s needle problem so interesting and surprising. China’s property sector is the

China’s property sector is the  C

C Brain development is a carefully choreographed dance. Neurons develop specialized functions and, in small hops, move through the brain to get into the correct position. The chemical signals coursing through the resulting network allow animals to think, feel, and live. In neurodevelopmental disorders (NDD), however, hundreds of mutations in the DNA can interrupt this process. But scientists still do not know how each of these mutations interrupts the neurons’ precise differentiation or migration patterns. Studying these defects directly in embryos or newborns is too dangerous, and other animal models may deviate from human development.

Brain development is a carefully choreographed dance. Neurons develop specialized functions and, in small hops, move through the brain to get into the correct position. The chemical signals coursing through the resulting network allow animals to think, feel, and live. In neurodevelopmental disorders (NDD), however, hundreds of mutations in the DNA can interrupt this process. But scientists still do not know how each of these mutations interrupts the neurons’ precise differentiation or migration patterns. Studying these defects directly in embryos or newborns is too dangerous, and other animal models may deviate from human development. I WAS AMONG MANY THAIS

I WAS AMONG MANY THAIS Consider how you hold a piece of chalk. Not by the handle: it doesn’t have one. Or, if it does, that handle is of the chalk’s own substance, flesh of its flesh, distinguishable only because it is the bit left in your hand when you can’t write anymore. A useless nub, or stub, or butt. Its persistence is a faint embarrassment, a remainder you don’t know what to do with—maybe you should stuff it in your pocket, or leave it in the tray with the erasers, or drop it on the floor and grind it into dust with your heel. It’s a waste, surely, just to throw it out. But it cannot be grafted onto another piece of chalk, not without gratuitous ingenuity, nor can it be used to hold anything else. It’s like the end of a pencil or of a filterless cigarette. Life is a midden of such abandoned handles. You didn’t even know they were handles, until they lost their grip and you were left holding them in a pinch, a pinch that can narrow, without your noticing, to contempt.

Consider how you hold a piece of chalk. Not by the handle: it doesn’t have one. Or, if it does, that handle is of the chalk’s own substance, flesh of its flesh, distinguishable only because it is the bit left in your hand when you can’t write anymore. A useless nub, or stub, or butt. Its persistence is a faint embarrassment, a remainder you don’t know what to do with—maybe you should stuff it in your pocket, or leave it in the tray with the erasers, or drop it on the floor and grind it into dust with your heel. It’s a waste, surely, just to throw it out. But it cannot be grafted onto another piece of chalk, not without gratuitous ingenuity, nor can it be used to hold anything else. It’s like the end of a pencil or of a filterless cigarette. Life is a midden of such abandoned handles. You didn’t even know they were handles, until they lost their grip and you were left holding them in a pinch, a pinch that can narrow, without your noticing, to contempt. A

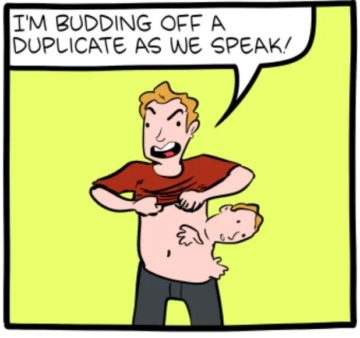

A It’s pretty clear that, on a direct one-v-one cage match, an asexual organism would have much better fitness than a similarly-shaped sexual organism. And yet, all the macroscopic species, including ourselves, do it. What gives?

It’s pretty clear that, on a direct one-v-one cage match, an asexual organism would have much better fitness than a similarly-shaped sexual organism. And yet, all the macroscopic species, including ourselves, do it. What gives?