Stanley Fish in The Chronicle of Higher Education:

University administrators faced with the challenge of responding to the various (and opposed) constituencies invested in the Hamas-Israel war have come up with a number of strategies.

University administrators faced with the challenge of responding to the various (and opposed) constituencies invested in the Hamas-Israel war have come up with a number of strategies.

- Condemn one side and express sympathy with the other, a sure loser.

- Condemn both sides, an even surer loser; all parties will feel aggrieved.

- Support the legitimate aspirations of both sides and reject violence; you will be faulted for occupying a perch so lofty that the pressing issues of the day disappear.

- Issue a general statement in support of peace and diplomatic negotiation; you will be accused of trafficking in pious platitudes that provide no firm guidance.

- Stay silent, say nothing.

Staying silent and saying nothing is the right thing to do, but it has been criticized by leaders like Patricia McGuire, president of Trinity Washington University, who declared that “neutrality is a cop-out.” But staying silent, properly understood, is not neutrality. Neutrality is a position you take after considering the alternatives and affirmatively deciding not to come down in either direction. It is in the fray, even if it pretends to be above the fray. Staying silent, as I urge it, means refusing to have a position.

More here. (Note: Thanks to dear friend Sharon Cameron)

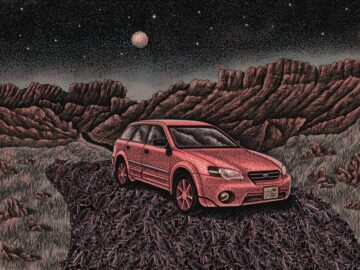

At twenty-six, in 2006, the year before the iPhone launched, I found myself driving a red Subaru Outback—the color was technically “claret metallic,” the friend who’d lent me the car had told me, in case I ever wanted to touch up the paint—on Highway 12 in Utah. I was heading to the East Bay after a painful breakup in New York. I remember, wrongly, that I was listening to a book on tape, a work by a prominent linguist, as I moved through the alien landscape, jagged formations of red rock towering against a cloudless sky.

At twenty-six, in 2006, the year before the iPhone launched, I found myself driving a red Subaru Outback—the color was technically “claret metallic,” the friend who’d lent me the car had told me, in case I ever wanted to touch up the paint—on Highway 12 in Utah. I was heading to the East Bay after a painful breakup in New York. I remember, wrongly, that I was listening to a book on tape, a work by a prominent linguist, as I moved through the alien landscape, jagged formations of red rock towering against a cloudless sky.

Ignacio Silva Neira in Phenomenal World:

Ignacio Silva Neira in Phenomenal World: T

T The Latin American Boom of the 1960s and ‘70s is associated with some of contemporary Spanish-language literature’s most towering figures, among them Julio Cortázar, Carlos Fuentes, Mario Vargas Llosa, and Gabriel García Márquez. But of all the

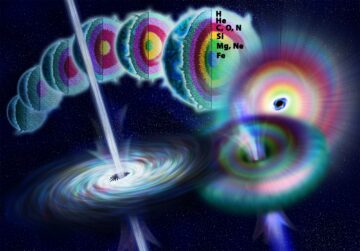

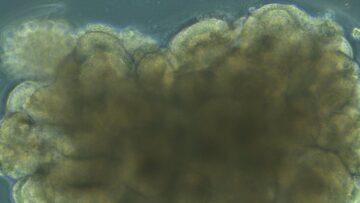

The Latin American Boom of the 1960s and ‘70s is associated with some of contemporary Spanish-language literature’s most towering figures, among them Julio Cortázar, Carlos Fuentes, Mario Vargas Llosa, and Gabriel García Márquez. But of all the  A tiny ball of brain cells hums with activity as it sits atop an array of electrodes. For two days, it receives a pattern of electrical zaps, each stimulation encoding the speech peculiarities of eight people. By day three, it can discriminate between speakers. Dubbed Brainoware, the system raises the bar for biocomputing by tapping into 3D brain organoids, or “mini-brains.” These models, usually grown from human stem cells, rapidly expand into a variety of neurons knitted into neural networks.

A tiny ball of brain cells hums with activity as it sits atop an array of electrodes. For two days, it receives a pattern of electrical zaps, each stimulation encoding the speech peculiarities of eight people. By day three, it can discriminate between speakers. Dubbed Brainoware, the system raises the bar for biocomputing by tapping into 3D brain organoids, or “mini-brains.” These models, usually grown from human stem cells, rapidly expand into a variety of neurons knitted into neural networks. “Class consciousness takes a vacation while we’re in the thrall of this book,” Barbara Grizzuti Harrison

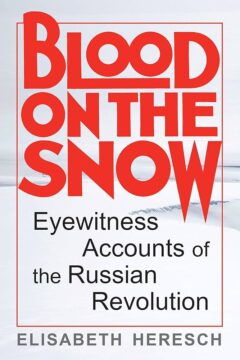

“Class consciousness takes a vacation while we’re in the thrall of this book,” Barbara Grizzuti Harrison  Sometimes when I’m looking out across the northern meadow of Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, or even the concrete parking lot outside my office window, I wonder if someone like Shakespeare or Emily Dickinson could have taken in the same view and seen more. I don’t mean making out blurry details or more objects in the scene. But through the lens of their minds, could they encounter the exact same world as me and yet have a richer experience? One way to answer that question, at least as a thought experiment, could be to compare the electrical activity inside our brains while gazing out upon the same scene, and running some statistical analysis designed to actually tell us whose brain activity indicates more richness. But that’s just a loopy thought experiment, right?

Sometimes when I’m looking out across the northern meadow of Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, or even the concrete parking lot outside my office window, I wonder if someone like Shakespeare or Emily Dickinson could have taken in the same view and seen more. I don’t mean making out blurry details or more objects in the scene. But through the lens of their minds, could they encounter the exact same world as me and yet have a richer experience? One way to answer that question, at least as a thought experiment, could be to compare the electrical activity inside our brains while gazing out upon the same scene, and running some statistical analysis designed to actually tell us whose brain activity indicates more richness. But that’s just a loopy thought experiment, right? “Earthrise, that iconic photograph

“Earthrise, that iconic photograph  Art is useless, said Wilde. Art is for art’s sake—that is, for beauty’s sake. But why do we possess a sense of beauty to begin with? A question we will never answer. Perhaps it’s just a kind of superfluity of sexual attraction. Nature needs us to feel drawn to other human bodies, but evolution is imprecise. In order to go far enough, to make that feeling strong enough, it went too far. Others are powerfully lovely to us, but so, in a strangely different, strangely similar way, are flowers and sunsets. Art, in turn, this line of thought might go, is a response to natural beauty. Stunned by it, we seek to rival it, to reproduce it, to prolong it. Flowers fade, sunsets melt from moment to moment; the love of bodies brings us grief. Art abides. “When old age shall this generational waste, / Thou shalt remain.”

Art is useless, said Wilde. Art is for art’s sake—that is, for beauty’s sake. But why do we possess a sense of beauty to begin with? A question we will never answer. Perhaps it’s just a kind of superfluity of sexual attraction. Nature needs us to feel drawn to other human bodies, but evolution is imprecise. In order to go far enough, to make that feeling strong enough, it went too far. Others are powerfully lovely to us, but so, in a strangely different, strangely similar way, are flowers and sunsets. Art, in turn, this line of thought might go, is a response to natural beauty. Stunned by it, we seek to rival it, to reproduce it, to prolong it. Flowers fade, sunsets melt from moment to moment; the love of bodies brings us grief. Art abides. “When old age shall this generational waste, / Thou shalt remain.” In form, Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis is modeled loosely on Thomas More’s Utopia. A ship full of European sailors lands on a previously unknown island in the Americas where they find a civilized society in many ways superior to their own. The narrator describes the customs and institutions of this society, which in Bacon is called “Bensalem,” Hebrew for “son of peace.” Sometimes Bacon echoes, sometimes improves upon, More’s earlier work. But at the end of the story, Bacon turns to focus solely on the most original feature of the island, an institution called Solomon’s House, or the College of the Six Days Works.

In form, Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis is modeled loosely on Thomas More’s Utopia. A ship full of European sailors lands on a previously unknown island in the Americas where they find a civilized society in many ways superior to their own. The narrator describes the customs and institutions of this society, which in Bacon is called “Bensalem,” Hebrew for “son of peace.” Sometimes Bacon echoes, sometimes improves upon, More’s earlier work. But at the end of the story, Bacon turns to focus solely on the most original feature of the island, an institution called Solomon’s House, or the College of the Six Days Works.