queer ancestor(s)

at most, you are a whisper

that my mother covertly deals

over the kitchen table, eyes shifting

looking out for all vengeful ghosts

both dead and alive

she thumbs through photographs nonchalantly

her index finger stopping briefly

to shine a light, so fast, I almost missed you

but there, my pupil widens

and swallows whole

the proof of your existence

trailed by a story of maybes,

of beliefs,

of secrets,

passing by, burning bright

small shooting star

on the horizon of my life

I want to look back and wish upon you

to ask for your unabashed truth and

yank it down so that I can

thread the glow of your being through mine

by Amanda Gómez Sánchez

from Bodega Magazine

Novelist Hanif Kureishi sustained life-changing injuries when he collapsed and landed on his head on Boxing Day last year. Left without the use of his arms and legs, the award-winning writer of The Buddha of Suburbia and My Beautiful Laundrette has charted his experience in brutally-honest blog posts. He credits his sense of purpose to his relationship with his responsive readers. A year on, he joined BBC Radio 4’s Today programme as a guest editor and described the accident’s profound impact on his life.

Novelist Hanif Kureishi sustained life-changing injuries when he collapsed and landed on his head on Boxing Day last year. Left without the use of his arms and legs, the award-winning writer of The Buddha of Suburbia and My Beautiful Laundrette has charted his experience in brutally-honest blog posts. He credits his sense of purpose to his relationship with his responsive readers. A year on, he joined BBC Radio 4’s Today programme as a guest editor and described the accident’s profound impact on his life. Ozempic and other drugs like it have proven powerful at regulating blood sugar and driving weight loss. Now, scientists are exploring whether they might be just as transformative in treating a wide range of other conditions, from addiction and liver disease to a common cause of infertility. “It’s like a snowball that turned into an avalanche,” said Lindsay Allen, a health economist at Northwestern Medicine. As the drugs gain momentum, she said, “they’re leaving behind them this completely reshaped landscape.” Much of the research on other uses of semaglutide, the compound in Ozempic and Wegovy, and tirzepatide, the substance in Mounjaro and Zepbound, is only in the early stages. One of the biggest questions scientists are seeking to answer: Do the benefits of these drugs just boil down to weight loss? Or do they have other effects, like tamping down inflammation in the body or quieting the brain’s compulsive thoughts, that would make it possible to treat far more illnesses?

Ozempic and other drugs like it have proven powerful at regulating blood sugar and driving weight loss. Now, scientists are exploring whether they might be just as transformative in treating a wide range of other conditions, from addiction and liver disease to a common cause of infertility. “It’s like a snowball that turned into an avalanche,” said Lindsay Allen, a health economist at Northwestern Medicine. As the drugs gain momentum, she said, “they’re leaving behind them this completely reshaped landscape.” Much of the research on other uses of semaglutide, the compound in Ozempic and Wegovy, and tirzepatide, the substance in Mounjaro and Zepbound, is only in the early stages. One of the biggest questions scientists are seeking to answer: Do the benefits of these drugs just boil down to weight loss? Or do they have other effects, like tamping down inflammation in the body or quieting the brain’s compulsive thoughts, that would make it possible to treat far more illnesses?

Any time you walk outside, satellites may be watching you from space. There are currently

Any time you walk outside, satellites may be watching you from space. There are currently  The ongoing horrors unfolding in Israel and Gaza have deep-rooted origins that stem from a complex and contested question: Who has rights to the same territory?

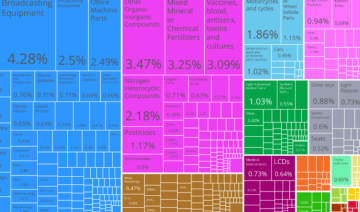

The ongoing horrors unfolding in Israel and Gaza have deep-rooted origins that stem from a complex and contested question: Who has rights to the same territory? Maria Haro Sly in Phenomenal World:

Maria Haro Sly in Phenomenal World: Around five years ago, David—a pseudonym—realized that he was fighting with his girlfriend all the time. On their first date, he had told her that he hoped to have sex with a thousand women before he died. They’d eventually agreed to have an exclusive relationship, but monogamy remained a source of tension. “I always used to tell her how much it bothered me,” he recalled. “I was an asshole.” An Israeli man now in his mid-thirties, David felt conflicted about other life issues. Did he want kids? How much should he prioritize making money? In his twenties, he’d tried psychotherapy several times; he would see a therapist for a few months, grow frustrated, stop, then repeat the cycle. He developed a theory. The therapists he saw wanted to help him become better adjusted given his current world view—but perhaps his world view was wrong. He wanted to examine how defensible his values were in the first place.

Around five years ago, David—a pseudonym—realized that he was fighting with his girlfriend all the time. On their first date, he had told her that he hoped to have sex with a thousand women before he died. They’d eventually agreed to have an exclusive relationship, but monogamy remained a source of tension. “I always used to tell her how much it bothered me,” he recalled. “I was an asshole.” An Israeli man now in his mid-thirties, David felt conflicted about other life issues. Did he want kids? How much should he prioritize making money? In his twenties, he’d tried psychotherapy several times; he would see a therapist for a few months, grow frustrated, stop, then repeat the cycle. He developed a theory. The therapists he saw wanted to help him become better adjusted given his current world view—but perhaps his world view was wrong. He wanted to examine how defensible his values were in the first place. The cosmetics entrepreneur Helena Rubinstein once observed, “There are no ugly women, only lazy ones.” The kind of beauty she had in mind is an ambivalent gift. On the one hand, it is not confined to the biologically blessed but available to everyone; on the other, it is a hard-earned prize, a product of ritualistic and often painstaking devotions at the mirror. Is this sort of beauty worth pursuing? Some feminist thinkers have bashed it as a superficial distraction. “Taught from infancy that beauty is woman’s sceptre, the mind shapes itself to the body, and roaming round its gilt cage, only seeks to adorn its prison,” Mary Wollstonecraft wrote disdainfully in 1792. Yet there is a tinge of misogyny to the familiar accusation that cosmetic projects are fluffy trivialities. Perhaps there is more truth (and more respect) to be found in the view of the novelist Henry James, who once described a female character’s flair for fashion as a form of “genius.”

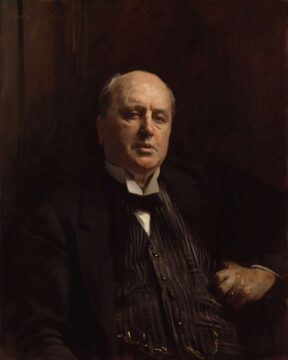

The cosmetics entrepreneur Helena Rubinstein once observed, “There are no ugly women, only lazy ones.” The kind of beauty she had in mind is an ambivalent gift. On the one hand, it is not confined to the biologically blessed but available to everyone; on the other, it is a hard-earned prize, a product of ritualistic and often painstaking devotions at the mirror. Is this sort of beauty worth pursuing? Some feminist thinkers have bashed it as a superficial distraction. “Taught from infancy that beauty is woman’s sceptre, the mind shapes itself to the body, and roaming round its gilt cage, only seeks to adorn its prison,” Mary Wollstonecraft wrote disdainfully in 1792. Yet there is a tinge of misogyny to the familiar accusation that cosmetic projects are fluffy trivialities. Perhaps there is more truth (and more respect) to be found in the view of the novelist Henry James, who once described a female character’s flair for fashion as a form of “genius.” “King of New York” was the epithet given to him by David Bowie, an obsessive Velvets fan who rescued Reed’s lacklustre solo career by producing Transformer, which spawned his biggest hit, Walk on the Wild Side. It’s also the title of Will Hermes’s meticulous yet vivid new biography, the first to draw on the archive donated to the New York Public Library by Reed’s widow Laurie Anderson. As in his 2011 book Love Goes to Buildings on Fire, about the city’s mid-70s musical landscape, Hermes expertly conjures the different scenes Reed inhabited, placing him amid a rich cast of collaborators, friends and lovers.

“King of New York” was the epithet given to him by David Bowie, an obsessive Velvets fan who rescued Reed’s lacklustre solo career by producing Transformer, which spawned his biggest hit, Walk on the Wild Side. It’s also the title of Will Hermes’s meticulous yet vivid new biography, the first to draw on the archive donated to the New York Public Library by Reed’s widow Laurie Anderson. As in his 2011 book Love Goes to Buildings on Fire, about the city’s mid-70s musical landscape, Hermes expertly conjures the different scenes Reed inhabited, placing him amid a rich cast of collaborators, friends and lovers. Forget everything you’ve ever heard about less being more, about economy of syntax, about the read-between-the-lines profundity of wide-margined, double-spaced “spare prose.” To read a paragraph by Henry James — a single one can sprawl across pages — is to luxuriate in linguistic excess.

Forget everything you’ve ever heard about less being more, about economy of syntax, about the read-between-the-lines profundity of wide-margined, double-spaced “spare prose.” To read a paragraph by Henry James — a single one can sprawl across pages — is to luxuriate in linguistic excess. Police officers are often the last to know when someone is being conned. A worried son might spot unusual payments on his elderly father’s bank statement. A concerned friend will do a reverse-image search on a suspiciously good-looking dating-app match. A fraudster will run out of excuses as to why they can’t meet. A horrible realisation will dawn and a report will be filed.

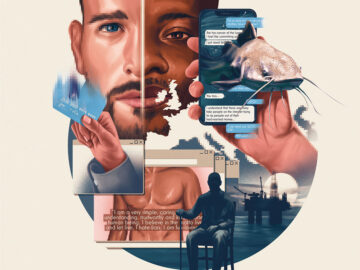

Police officers are often the last to know when someone is being conned. A worried son might spot unusual payments on his elderly father’s bank statement. A concerned friend will do a reverse-image search on a suspiciously good-looking dating-app match. A fraudster will run out of excuses as to why they can’t meet. A horrible realisation will dawn and a report will be filed.