Lydialyle Gibson in Harvard Magazine:

A specialist in epistemology and the philosophy of mind, Siegel has always been fascinated by perception: what and how we see, and the effect that has on what we can know. Her 2010 book, The Contents of Visual Experience, argued that conscious visual perception includes all kinds of complex properties: not just color, shape, light, and motion, but other, richer attributes, too. For instance, it encompasses what kind of thing we see—a tree, a bicycle, a dog?—and causal characteristics, like the property a knife can have while slicing through a piece of bread. Perception can even involve personal identity, Siegel argued: the property of being John Malkovich. The book’s central claim was that being able to visually recognize things, such as one’s own neighborhood, or pine trees, or John Malkovich, can influence how those things look to the person who sees them.

A specialist in epistemology and the philosophy of mind, Siegel has always been fascinated by perception: what and how we see, and the effect that has on what we can know. Her 2010 book, The Contents of Visual Experience, argued that conscious visual perception includes all kinds of complex properties: not just color, shape, light, and motion, but other, richer attributes, too. For instance, it encompasses what kind of thing we see—a tree, a bicycle, a dog?—and causal characteristics, like the property a knife can have while slicing through a piece of bread. Perception can even involve personal identity, Siegel argued: the property of being John Malkovich. The book’s central claim was that being able to visually recognize things, such as one’s own neighborhood, or pine trees, or John Malkovich, can influence how those things look to the person who sees them.

But as she was finishing that book, another question began to bother her: if being able to recognize your neighborhood influences how it looks to you, then couldn’t beliefs, desires, and fears do the same? And if prior beliefs could influence someone’s visual experience, how might those experiences, in turn, strengthen those very beliefs?

More here.

Reclusive and disaffected, Ettore Majorana liked to work in the shadows. But after his friend Emilio Segrè dragged him into Enrico Fermi’s elite Roman physics club in the late 1920s, Majorana’s stature in atomic physics quickly grew. His mostly unpublished premonitions were eerily prescient: Among others, he famously intuited the existence of the neutron from prior experiments. And in 1937, he

Reclusive and disaffected, Ettore Majorana liked to work in the shadows. But after his friend Emilio Segrè dragged him into Enrico Fermi’s elite Roman physics club in the late 1920s, Majorana’s stature in atomic physics quickly grew. His mostly unpublished premonitions were eerily prescient: Among others, he famously intuited the existence of the neutron from prior experiments. And in 1937, he  HOW ROMANTIC IS J. M. COETZEE? At first the question, prompted by his eighteenth novel, The Pole, sounds like a joke. The journalist Rian Malan, who visited Coetzee’s office at the University of Cape Town in the early 1990s, reported that the novelist didn’t smoke, drink, eat meat, or, except on very rare occasions, laugh. “It helps to have a piercing gaze,” Coetzee wrote in one of eight essays on Beckett, and his own author photographs show a man who, with his ironed shirts, unvainly swept-back hair, and eyes that would win any no-blinking competition, resembles a semi-retired notary public, or a mob boss who hasn’t got his hands dirty for decades. In his work, too, he offers little in the way of solace or solicitude, presenting a harsh world in parched prose.

HOW ROMANTIC IS J. M. COETZEE? At first the question, prompted by his eighteenth novel, The Pole, sounds like a joke. The journalist Rian Malan, who visited Coetzee’s office at the University of Cape Town in the early 1990s, reported that the novelist didn’t smoke, drink, eat meat, or, except on very rare occasions, laugh. “It helps to have a piercing gaze,” Coetzee wrote in one of eight essays on Beckett, and his own author photographs show a man who, with his ironed shirts, unvainly swept-back hair, and eyes that would win any no-blinking competition, resembles a semi-retired notary public, or a mob boss who hasn’t got his hands dirty for decades. In his work, too, he offers little in the way of solace or solicitude, presenting a harsh world in parched prose. Bella Baxter, the heroine of Poor Things in both the book and the film, often feels like one of those peculiar characters who appear in philosophy. In “Epiphenomenal Qualia,” for example, the Australian analytic philosopher Frank Jackson tells us about Mary, a brilliant scientist who “for whatever reason” has always lived inside a black and white room, learning everything about the world by watching a black and white television. What will happen, Jackson wonders, when we let her out—what knowledge will she gain when she sees the blue sky?

Bella Baxter, the heroine of Poor Things in both the book and the film, often feels like one of those peculiar characters who appear in philosophy. In “Epiphenomenal Qualia,” for example, the Australian analytic philosopher Frank Jackson tells us about Mary, a brilliant scientist who “for whatever reason” has always lived inside a black and white room, learning everything about the world by watching a black and white television. What will happen, Jackson wonders, when we let her out—what knowledge will she gain when she sees the blue sky?

You’d never mistake a goat for a dog, but on an unseasonably warm afternoon in early September, I almost do. I’m in a red-brick barn in northern Germany, trying to keep my sanity amid some of the most unholy noises I’ve ever heard. Sixty Nigerian dwarf goats are taking turns crashing their horns against wooden stalls while unleashing a cacophony of bleats, groans, and retching wails that make it nearly impossible to hold a conversation. Then, amid the chaos, something remarkable happens. One of the animals raises her head over her enclosure and gazes pensively at me, her widely spaced eyes and odd, rectangular pupils seeking to make contact—and perhaps even connection.

You’d never mistake a goat for a dog, but on an unseasonably warm afternoon in early September, I almost do. I’m in a red-brick barn in northern Germany, trying to keep my sanity amid some of the most unholy noises I’ve ever heard. Sixty Nigerian dwarf goats are taking turns crashing their horns against wooden stalls while unleashing a cacophony of bleats, groans, and retching wails that make it nearly impossible to hold a conversation. Then, amid the chaos, something remarkable happens. One of the animals raises her head over her enclosure and gazes pensively at me, her widely spaced eyes and odd, rectangular pupils seeking to make contact—and perhaps even connection. For me, this will always be the year I became a grandparent. It will be the year I spent a lot of precious time with loved ones—whether on the pickleball court or over a rousing game of Settlers of Catan. And 2023 marked the first time I used artificial intelligence for work and other serious reasons, not just to mess around and create parody song lyrics for my friends.

For me, this will always be the year I became a grandparent. It will be the year I spent a lot of precious time with loved ones—whether on the pickleball court or over a rousing game of Settlers of Catan. And 2023 marked the first time I used artificial intelligence for work and other serious reasons, not just to mess around and create parody song lyrics for my friends. B

B Will an artificial intelligence (AI) superintelligence appear suddenly, or will scientists see it coming, and have a chance to warn the world? That’s a question that has received a lot of attention recently, with the rise of

Will an artificial intelligence (AI) superintelligence appear suddenly, or will scientists see it coming, and have a chance to warn the world? That’s a question that has received a lot of attention recently, with the rise of  In his new book Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon (2023), Michael Lewis has the difficult task of explaining why his subject, wunderkind Sam Bankman-Fried, co-founder of the multibillion-dollar cryptocurrency exchange FTX, who seemed tailor-made for the author’s patented oddball-outsider-disrupts-the-world shtick, was convicted for one of the biggest frauds in financial history. Like so many people both before and after crypto’s last big explosion in 2022, Lewis allows that he doesn’t know all that much about the underlying technologies, specifically blockchain, but is nevertheless compelled by the scene’s anarchic ambition. At one point, he throws up his hands and admits that crypto “often gets explained but somehow never stays explained.”

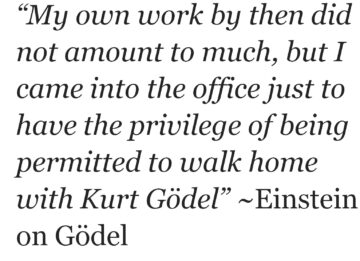

In his new book Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon (2023), Michael Lewis has the difficult task of explaining why his subject, wunderkind Sam Bankman-Fried, co-founder of the multibillion-dollar cryptocurrency exchange FTX, who seemed tailor-made for the author’s patented oddball-outsider-disrupts-the-world shtick, was convicted for one of the biggest frauds in financial history. Like so many people both before and after crypto’s last big explosion in 2022, Lewis allows that he doesn’t know all that much about the underlying technologies, specifically blockchain, but is nevertheless compelled by the scene’s anarchic ambition. At one point, he throws up his hands and admits that crypto “often gets explained but somehow never stays explained.” When Einstein talks of someone in the superlative, you know that person would have been beyond special. Indeed, Kurt Gödel was no ordinary man. Perhaps the greatest logician of all time, Gödel’s incompleteness theorems altered the very fabric of the epistemology of mathematical systems.

When Einstein talks of someone in the superlative, you know that person would have been beyond special. Indeed, Kurt Gödel was no ordinary man. Perhaps the greatest logician of all time, Gödel’s incompleteness theorems altered the very fabric of the epistemology of mathematical systems. In 1951, just six years after World War II, Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany signed the Treaty of Paris, establishing the European Coal and Steel Community.

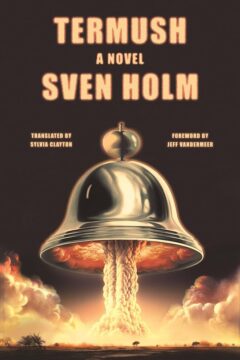

In 1951, just six years after World War II, Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany signed the Treaty of Paris, establishing the European Coal and Steel Community. Halfway through Sven Holm’s taut unfolding nightmare, Termush, the unnamed narrator encounters “ploughed-up and trampled gardens” where “stone creatures are the sole survivors.” Holm describes these statues as “curious forms, the bodies like great ill-defined blocks, designed more to evoke a sense of weight and mass than to suggest power in the muscles and sinews.” Later, a guest of the gated, walled hotel for the rich from which the novel takes its name relates a dream in which “light streamed out of every object; it shone through robes and skin and the flesh on the bones, the leaves on the trees … to reveal the innermost vulnerable marrow of people and plants.” The same could describe the novel, which accrues its strange effects via both this stricken, continuous revealing and the “curious forms” of a solid, impervious setting, in which the ordinary elements of our world come to seem alien through the lens of nuclear catastrophe.

Halfway through Sven Holm’s taut unfolding nightmare, Termush, the unnamed narrator encounters “ploughed-up and trampled gardens” where “stone creatures are the sole survivors.” Holm describes these statues as “curious forms, the bodies like great ill-defined blocks, designed more to evoke a sense of weight and mass than to suggest power in the muscles and sinews.” Later, a guest of the gated, walled hotel for the rich from which the novel takes its name relates a dream in which “light streamed out of every object; it shone through robes and skin and the flesh on the bones, the leaves on the trees … to reveal the innermost vulnerable marrow of people and plants.” The same could describe the novel, which accrues its strange effects via both this stricken, continuous revealing and the “curious forms” of a solid, impervious setting, in which the ordinary elements of our world come to seem alien through the lens of nuclear catastrophe.