Melissa Anderson at Bookforum:

I HAVE FREQUENTLY BEEN SEATED in the dark near those who have variously been called “the pilly-sweater crowd,” “cinemaniacs,” or “Titus-heads” (referring to the two main movie theaters at MoMA). They are pejorative terms for a certain type of New York City cinephile, one whose zeal for the seventh art seems to have been leached of all pleasure and has instead transmogrified into grim compulsion. Demographically, they are often (but not always) white, male, and middle-aged or older.

I HAVE FREQUENTLY BEEN SEATED in the dark near those who have variously been called “the pilly-sweater crowd,” “cinemaniacs,” or “Titus-heads” (referring to the two main movie theaters at MoMA). They are pejorative terms for a certain type of New York City cinephile, one whose zeal for the seventh art seems to have been leached of all pleasure and has instead transmogrified into grim compulsion. Demographically, they are often (but not always) white, male, and middle-aged or older.

The eponymous protagonist of Jeremy Cooper’s novel Brian fits that profile, yet he is a Londoner. At age thirty-nine he becomes a “buff” or a “regular” at the BFI Southbank (known as the National Film Theatre from 1951 to 2007), anodyne terms that he accepts, though “categories and titles worried him, a form, he felt, of social control.” When his colleagues at the Camden Housing Department (where he is responsible for keeping lease and freehold records up to date) call him a “movie geek,” he recoils at the expression, “prepar[ing] in response the simple description of himself as a man who loved cinema.”

more here.

A

A I

I Ernest Becker was already dying when “The Denial of Death” was published 50 years ago this past fall. “This is a test of everything I’ve written about death,” he told a visitor to his Vancouver hospital room. Throughout his career as a cultural anthropologist, Becker had charted the undiscovered country that awaits us all. Now only 49 but losing a battle to colon cancer, he was being dispatched there himself. By the time his book was

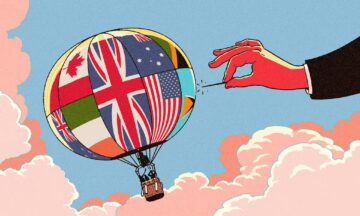

Ernest Becker was already dying when “The Denial of Death” was published 50 years ago this past fall. “This is a test of everything I’ve written about death,” he told a visitor to his Vancouver hospital room. Throughout his career as a cultural anthropologist, Becker had charted the undiscovered country that awaits us all. Now only 49 but losing a battle to colon cancer, he was being dispatched there himself. By the time his book was  The emergence of English as the predominant (though not exclusive) international language is seen by many as a positive phenomenon with several practical advantages and no downside. However, it also raises problems that are slowly beginning to be understood and studied.

The emergence of English as the predominant (though not exclusive) international language is seen by many as a positive phenomenon with several practical advantages and no downside. However, it also raises problems that are slowly beginning to be understood and studied. Some say that history begins with writing; we say that history begins with clothing. In the beginning, there was clothing made from skins that early humans removed from animals, processed, and then tailored to fit the human body; this technique is still used in the Arctic. Next came textiles. The first weavers would weave textiles in the shape of animal hides or raise the nap of the fabric’s surface to mimic the appearance of fur, making the fabric warmer and more comfortable.

Some say that history begins with writing; we say that history begins with clothing. In the beginning, there was clothing made from skins that early humans removed from animals, processed, and then tailored to fit the human body; this technique is still used in the Arctic. Next came textiles. The first weavers would weave textiles in the shape of animal hides or raise the nap of the fabric’s surface to mimic the appearance of fur, making the fabric warmer and more comfortable. This was during the Long 2010s (2009-2022), a decade during which there occurred more mass protests than any decade in history. The protests were against the usual suspects: capitalism, racism, imperialism, greed, corruption. Two new books, Vincent Bevins’s If We Burn: The Mass Protest Decade and the Missing Revolution and The Populist Moment: The Left After the Great Recession by Arthur Borriello and Anton Jäger, are about these protests and why they seemed to summon more of what they protested against—more greed, more racism, more corruption. They take different approaches. The Populist Moment is an academic investigation into the electoral failures of left-wing candidates in Europe and the United States (Bernie Sanders, Jeremy Corbyn, Jean-Luc Melenchon, Greece’s Syriza party), while If We Burn is a journalistic account of street protests in the Third World (Brazil, Indonesia, Chile) as well as Turkey and Ukraine.

This was during the Long 2010s (2009-2022), a decade during which there occurred more mass protests than any decade in history. The protests were against the usual suspects: capitalism, racism, imperialism, greed, corruption. Two new books, Vincent Bevins’s If We Burn: The Mass Protest Decade and the Missing Revolution and The Populist Moment: The Left After the Great Recession by Arthur Borriello and Anton Jäger, are about these protests and why they seemed to summon more of what they protested against—more greed, more racism, more corruption. They take different approaches. The Populist Moment is an academic investigation into the electoral failures of left-wing candidates in Europe and the United States (Bernie Sanders, Jeremy Corbyn, Jean-Luc Melenchon, Greece’s Syriza party), while If We Burn is a journalistic account of street protests in the Third World (Brazil, Indonesia, Chile) as well as Turkey and Ukraine. From a certain point of view, the extraordinary abundance of chickens might be seen as a positive development: Here is a source of protein that is cheaply produced, transportable, happily consumed by a huge number of people across the world. And thanks in part to Peterson’s efforts at improving feed conversion efficiency, chicken has a much slimmer carbon impact than beef, which contributes more than

From a certain point of view, the extraordinary abundance of chickens might be seen as a positive development: Here is a source of protein that is cheaply produced, transportable, happily consumed by a huge number of people across the world. And thanks in part to Peterson’s efforts at improving feed conversion efficiency, chicken has a much slimmer carbon impact than beef, which contributes more than  Shortly after Rachel Bespaloff’s suicide in 1949, her friend Jean Wahl published fragments from her final unfinished project. ‘The Instant and Freedom’ condensed themes that occupied the Ukrainian-French philosopher throughout her life: music, rhythm, corporeality, movement and time. One of Bespaloff’s key ideas, ‘the instant’, is less a fragment of duration than a life-changing event, a moment of embodied metamorphosis. In the midst of a noisy world, torn between transience and eternity, the human being listens to the sound of history. Had she completed and published it, ‘The Instant and Freedom’ might have become the masterpiece of an important early existentialist thinker. Instead, her name is hardly mentioned today.

Shortly after Rachel Bespaloff’s suicide in 1949, her friend Jean Wahl published fragments from her final unfinished project. ‘The Instant and Freedom’ condensed themes that occupied the Ukrainian-French philosopher throughout her life: music, rhythm, corporeality, movement and time. One of Bespaloff’s key ideas, ‘the instant’, is less a fragment of duration than a life-changing event, a moment of embodied metamorphosis. In the midst of a noisy world, torn between transience and eternity, the human being listens to the sound of history. Had she completed and published it, ‘The Instant and Freedom’ might have become the masterpiece of an important early existentialist thinker. Instead, her name is hardly mentioned today. A

A Wearing an electrode-studded cap bristling with wires, a young man silently reads a sentence in his head. Moments later, a Siri-like voice breaks in,

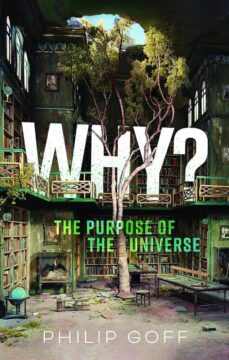

Wearing an electrode-studded cap bristling with wires, a young man silently reads a sentence in his head. Moments later, a Siri-like voice breaks in,  Why is there something rather than nothing? It’s meant to be the great unanswerable question. It’s certainly a poser. It would have been simpler if there’d been nothing: there wouldn’t be anything to explain.

Why is there something rather than nothing? It’s meant to be the great unanswerable question. It’s certainly a poser. It would have been simpler if there’d been nothing: there wouldn’t be anything to explain. For almost all of human existence, our species has been roaming the planet, living in small groups, hunting and gathering, moving to new areas when the climate was favourable, retreating when it turned nasty. For hundreds of thousands of years, our ancestors used fire to cook and warm themselves. They made tools, shelters, clothing and jewellery – although their possessions were limited to what they could carry. They occasionally came across other hominins, like Neanderthals, and sometimes had sex with them. Across vast swathes of time, history played out, unrecorded.

For almost all of human existence, our species has been roaming the planet, living in small groups, hunting and gathering, moving to new areas when the climate was favourable, retreating when it turned nasty. For hundreds of thousands of years, our ancestors used fire to cook and warm themselves. They made tools, shelters, clothing and jewellery – although their possessions were limited to what they could carry. They occasionally came across other hominins, like Neanderthals, and sometimes had sex with them. Across vast swathes of time, history played out, unrecorded.