Katherine Gammon in Nautilus:

On the top of Mount Everest, in the Mariana Trench, in the human placenta, and babies’ feces: Plastics are everywhere. They are built to last, and last they do: A plastic bag can endure for 20 years in the environment, and a disposable diaper, soiled or not, up to 200. When they do finally break down into microplastics—smaller than 1 micrometer, or about 1/70th the diameter of a human hair—they can become difficult to detect. These microplastics are so ubiquitous in the environment that some scientists think we should track how they cycle through the global oceans, atmosphere, and soil much in the same way we track carbon and phosphorus.

On the top of Mount Everest, in the Mariana Trench, in the human placenta, and babies’ feces: Plastics are everywhere. They are built to last, and last they do: A plastic bag can endure for 20 years in the environment, and a disposable diaper, soiled or not, up to 200. When they do finally break down into microplastics—smaller than 1 micrometer, or about 1/70th the diameter of a human hair—they can become difficult to detect. These microplastics are so ubiquitous in the environment that some scientists think we should track how they cycle through the global oceans, atmosphere, and soil much in the same way we track carbon and phosphorus.

Clouds: Researchers recently collected 28 samples of liquid from clouds at the top of Mount Tai in eastern China. They found microplastic fibers—from clothing, packaging, or tires—in their samples. Lower altitude clouds contained more particles. The older plastic particles, some of which attract elements like lead, oxygen, and mercury, could lead to more cloud development, according to a paper published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology Letters.

More here.

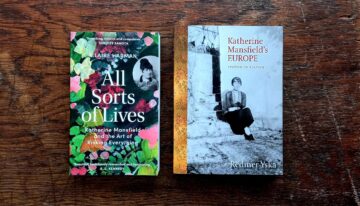

Douglas Adams called him “the greatest comic writer ever.” Hilaire Belloc went so far as to pronounce him “the best living writer of English,” and rather than retract that excessive praise he explained it. P.G. Wodehouse had perfectly accomplished what he set out to do: create and sustain a world that would amuse us.

Douglas Adams called him “the greatest comic writer ever.” Hilaire Belloc went so far as to pronounce him “the best living writer of English,” and rather than retract that excessive praise he explained it. P.G. Wodehouse had perfectly accomplished what he set out to do: create and sustain a world that would amuse us.

G

G Plagiarism is one of academia’s oldest crimes, but Claudine Gay’s resignation as Harvard University’s president

Plagiarism is one of academia’s oldest crimes, but Claudine Gay’s resignation as Harvard University’s president  Just who is Vladimir Putin? In the 20-odd years he’s been in power, even the Russian leader’s physical appearance has undergone a series of ominous transformations. The alert but colourless apparatchik of his early years first became a smooth-faced enigma, then a tsar of such feline menace that you half expect to see bloody feathers at the corner of his mouth. And that’s nothing compared to the changes that have happened in Russia: at the dawn of the millennium it seemed to be stumbling towards democracy. It had, albeit imperfectly, such things as free speech and opposition politicians. Even Putin seemed to talk sincerely of partnership with his former cold war opponents. So what on earth happened?

Just who is Vladimir Putin? In the 20-odd years he’s been in power, even the Russian leader’s physical appearance has undergone a series of ominous transformations. The alert but colourless apparatchik of his early years first became a smooth-faced enigma, then a tsar of such feline menace that you half expect to see bloody feathers at the corner of his mouth. And that’s nothing compared to the changes that have happened in Russia: at the dawn of the millennium it seemed to be stumbling towards democracy. It had, albeit imperfectly, such things as free speech and opposition politicians. Even Putin seemed to talk sincerely of partnership with his former cold war opponents. So what on earth happened? One of the most important conceptual developments of the past few decades is the realisation that belief comes in degrees. We don’t just believe something or not: much of our thinking, and decision-making, is driven by varying levels of confidence. These confidence levels can be measured as probabilities, on a scale from zero to

One of the most important conceptual developments of the past few decades is the realisation that belief comes in degrees. We don’t just believe something or not: much of our thinking, and decision-making, is driven by varying levels of confidence. These confidence levels can be measured as probabilities, on a scale from zero to  Becca Rothfeld: The first question I wanted to ask is how to improve liberalism. Despite some misreadings of Liberalism Against Itself as illiberal, it’s very much not an anti-liberal book. It’s a book that’s disappointed with the direction that postwar liberalism has taken, but it’s also cautiously optimistic about the liberal tradition’s ability to redeem itself.

Becca Rothfeld: The first question I wanted to ask is how to improve liberalism. Despite some misreadings of Liberalism Against Itself as illiberal, it’s very much not an anti-liberal book. It’s a book that’s disappointed with the direction that postwar liberalism has taken, but it’s also cautiously optimistic about the liberal tradition’s ability to redeem itself. V

V I

I Toward the end of “The Light Room,”

Toward the end of “The Light Room,”