Joe Phelan in Edsitement:

When most people think of the civil rights movement, they think of Martin Luther King, Jr., whose “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in 1963, and his acceptance of the Peace Prize the following year, secured his place as the voice of non-violent, mass protest in the 1960s. Yet the movement achieved its greatest results—the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act—due to the competing and sometimes radical strategies and agendas of diverse individuals such as Malcolm X, whose birthday is celebrated on May 19. As one of the most powerful, controversial, and enigmatic figures of the movement he occupies a necessary place in social studies/history curricula.

When most people think of the civil rights movement, they think of Martin Luther King, Jr., whose “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in 1963, and his acceptance of the Peace Prize the following year, secured his place as the voice of non-violent, mass protest in the 1960s. Yet the movement achieved its greatest results—the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act—due to the competing and sometimes radical strategies and agendas of diverse individuals such as Malcolm X, whose birthday is celebrated on May 19. As one of the most powerful, controversial, and enigmatic figures of the movement he occupies a necessary place in social studies/history curricula.

Malcolm X’s embrace of black separatism shaped the debate over how to achieve freedom and equality in a nation that had long denied a portion of the American citizenry the full protection of their rights. It also laid the groundwork for the Black Power movement of the late sixties. Malcolm X believed that blacks were god’s chosen people. As a minister of the Nation of Islam, he preached fiery sermons on separation from whites, whom he believed were destined for divine punishment because of their longstanding oppression of blacks. Whites had proven themselves long on professing and short on practicing their ideals of equality and freedom, and Malcolm X thought only a separate nation for blacks could provide the basis for their self-improvement and advancement as a people.

More here. (Note: In honor of Black History Month, at least one post will be devoted to its 2024 theme of “African Americans and the Arts” throughout the month of February)

Although the Cather nuts among us are puzzled that she is not taught, and therefore read, as much as, say, Hemingway or Fitzgerald, Cather has actually had plenty of biographical and scholarly attention since her death in 1947. Within six years, her lifelong companion and literary executrix Edith Lewis had brought out Willa Cather Living: A Personal Record (Knopf, 1953), and her friend Elizabeth Sergeant produced Willa Cather: A Memoir (Lippincott, 1953). That same year, Knopf published E. K. Brown’s Willa Cather: A Critical Biography, a work authorized by Lewis and finished by Leon Edel when Professor Brown died young and in harness. In 1970, James Woodress contributed Willa Cather: Her Life and Art, a wonderful if briefish study, to something called the Pegasus American Authors series. In 1986 Oxford University Press published Sharon O’Brien’s Willa Cather: The Emerging Voice, and the 1980s also saw both a full-length biography from Woodress from the University of Nebraska Press and a definitive full treatment from the British critic and literary biographer Hermione Lee (Willa Cather: Double Lives) from Pantheon. Cather has also in recent decades been the subject of considerations at various lengths by Joan Acocella, Vivian Gornick, Toni Morrison, Katherine Anne Porter, Phyllis Rose, and Eudora Welty, among others. Clearly, she has always been a writer’s writer.

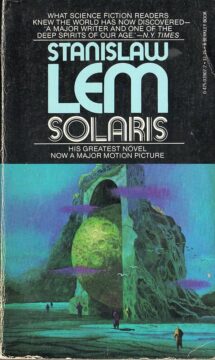

Although the Cather nuts among us are puzzled that she is not taught, and therefore read, as much as, say, Hemingway or Fitzgerald, Cather has actually had plenty of biographical and scholarly attention since her death in 1947. Within six years, her lifelong companion and literary executrix Edith Lewis had brought out Willa Cather Living: A Personal Record (Knopf, 1953), and her friend Elizabeth Sergeant produced Willa Cather: A Memoir (Lippincott, 1953). That same year, Knopf published E. K. Brown’s Willa Cather: A Critical Biography, a work authorized by Lewis and finished by Leon Edel when Professor Brown died young and in harness. In 1970, James Woodress contributed Willa Cather: Her Life and Art, a wonderful if briefish study, to something called the Pegasus American Authors series. In 1986 Oxford University Press published Sharon O’Brien’s Willa Cather: The Emerging Voice, and the 1980s also saw both a full-length biography from Woodress from the University of Nebraska Press and a definitive full treatment from the British critic and literary biographer Hermione Lee (Willa Cather: Double Lives) from Pantheon. Cather has also in recent decades been the subject of considerations at various lengths by Joan Acocella, Vivian Gornick, Toni Morrison, Katherine Anne Porter, Phyllis Rose, and Eudora Welty, among others. Clearly, she has always been a writer’s writer. In “Summa Technologiae,” Lem emphasizes how humanity, in thinking about the future, has often thought through the wrong questions. We can transmute other metals into gold now, but it was a misunderstanding that made us think we would still want to, he says. We can fly, but not by flapping our arms, since “even if we ourselves choose our end point, our way of getting there is chosen by Nature.” When Lem writes in “Summa” about artificial intelligence—or “intelligence amplifiers,” as he terms it—he says it’s likely possible that one day there will be an artificial intelligence ten thousand times smarter than us, but it won’t come from more advanced mathematics or algorithms. Instead, it comes from machines that can learn in a way similar to how we do—which is what is happening. With the Electronic Bard, Lem derides the worry that our own human creativity will be dwarfed. That, like the questions of the alchemists, he suggests, is the wrong concern. But what is the right one?

In “Summa Technologiae,” Lem emphasizes how humanity, in thinking about the future, has often thought through the wrong questions. We can transmute other metals into gold now, but it was a misunderstanding that made us think we would still want to, he says. We can fly, but not by flapping our arms, since “even if we ourselves choose our end point, our way of getting there is chosen by Nature.” When Lem writes in “Summa” about artificial intelligence—or “intelligence amplifiers,” as he terms it—he says it’s likely possible that one day there will be an artificial intelligence ten thousand times smarter than us, but it won’t come from more advanced mathematics or algorithms. Instead, it comes from machines that can learn in a way similar to how we do—which is what is happening. With the Electronic Bard, Lem derides the worry that our own human creativity will be dwarfed. That, like the questions of the alchemists, he suggests, is the wrong concern. But what is the right one? W

W On a recent October morning, Rob Kirby stood in front of a roomful of mathematicians and told them not to feel bound by the way he’d done things in the past.

On a recent October morning, Rob Kirby stood in front of a roomful of mathematicians and told them not to feel bound by the way he’d done things in the past. Asterisk: The overarching question in your transit policy career has been: Why is America so bad at building transit systems? Earlier this year, your team at NYU released a massive report comparing transit costs in Istanbul, Italy, Sweden and Boston, and then, of course, New York. It culminates in your fantastic case study of the Second Avenue subway line. And that’s where I wanted to start. What went wrong?

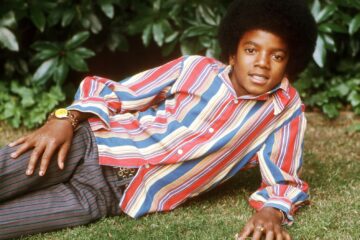

Asterisk: The overarching question in your transit policy career has been: Why is America so bad at building transit systems? Earlier this year, your team at NYU released a massive report comparing transit costs in Istanbul, Italy, Sweden and Boston, and then, of course, New York. It culminates in your fantastic case study of the Second Avenue subway line. And that’s where I wanted to start. What went wrong? He was, in the end, precisely what he claimed and struggled to be: the biggest star in the world. If there had been any doubt, it ended on the afternoon of June 25th, 2009, when the news broke that

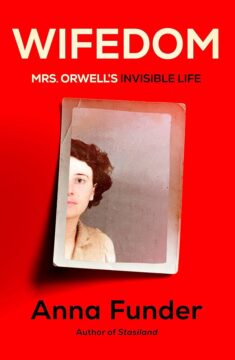

He was, in the end, precisely what he claimed and struggled to be: the biggest star in the world. If there had been any doubt, it ended on the afternoon of June 25th, 2009, when the news broke that  Eileen O’Shaughnessy married George Orwell in 1936 and remained married to him until her unexpected and untimely death in 1945. Anna Funder’s Wifedom is primarily an analysis of that nine-year marriage, which Funder concludes as having been throughout to Eileen’s disadvantage, an ‘arms race to mutual self-destruction: she by selflessness, and he by disappearing into the greedy double life that is the artist’s, of self + work’. The Orwell that emerges from this account was variously exploitative, neglectful, hypocritical and adulterous, not to mention a tepid and unremarkable lover and, who knows, a tortured and in-denial homosexual. Separate from his life with Eileen he was an inept seducer, occasional stalker, and, on at least two occasions, thwarted rapist.

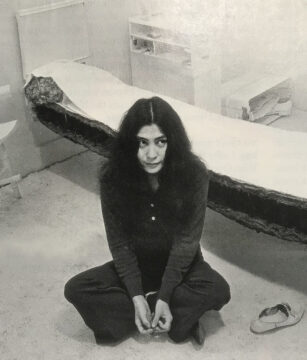

Eileen O’Shaughnessy married George Orwell in 1936 and remained married to him until her unexpected and untimely death in 1945. Anna Funder’s Wifedom is primarily an analysis of that nine-year marriage, which Funder concludes as having been throughout to Eileen’s disadvantage, an ‘arms race to mutual self-destruction: she by selflessness, and he by disappearing into the greedy double life that is the artist’s, of self + work’. The Orwell that emerges from this account was variously exploitative, neglectful, hypocritical and adulterous, not to mention a tepid and unremarkable lover and, who knows, a tortured and in-denial homosexual. Separate from his life with Eileen he was an inept seducer, occasional stalker, and, on at least two occasions, thwarted rapist. Halfway round the new “Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind” exhibition at Tate Modern (on until 1 September) I enter into a kind of record-shop listening booth that is decorated with her album covers and filled with individual sets of headphones. It’s the least crowded section of the show – Yoko’s music still perhaps not being people’s favourite thing about her – but I’m happy that her records are included here. So I put on a song I love, “Death of Samantha”, from 1973.

Halfway round the new “Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind” exhibition at Tate Modern (on until 1 September) I enter into a kind of record-shop listening booth that is decorated with her album covers and filled with individual sets of headphones. It’s the least crowded section of the show – Yoko’s music still perhaps not being people’s favourite thing about her – but I’m happy that her records are included here. So I put on a song I love, “Death of Samantha”, from 1973. Can’t tell you what

Can’t tell you what  Under cover of darkness, I boarded a Navy vessel at a heavily guarded military base along the Eastern Seaboard. The location and time of departure, as well as the direction and distance of travel, were unknown to me. Adding to the sense of secrecy, a towering sailor in camouflage stood in the rain, examining my belongings for electronics that might leave a digital trail an adversary could intercept and exploit.

Under cover of darkness, I boarded a Navy vessel at a heavily guarded military base along the Eastern Seaboard. The location and time of departure, as well as the direction and distance of travel, were unknown to me. Adding to the sense of secrecy, a towering sailor in camouflage stood in the rain, examining my belongings for electronics that might leave a digital trail an adversary could intercept and exploit. “Was it a government action, or did they do it themselves because of pressure?”

“Was it a government action, or did they do it themselves because of pressure?”