Evan Lerner in Seed Magazine:

Evan Lerner in Seed Magazine:

The discovery of a new planet has always been exciting, but the bloom is starting to come off the rose now that we’ve done it more than 400 times. A University of California–Santa Cruz team announced the discovery of six new planets orbiting two stars earlier this week, but they weren’t even the toast of the exoplanetology world, much less international newsmakers. Those honors went to a team led by Harvard’s David Charbonneau.

Quality trumps quantity when it comes to such discoveries, and Charbonneau’s planet has a number of newsworthy traits. At more than six times our own planet’s mass, it’s a “super-Earth,” but this new world’s relatively low density means it’s likely made mostly of water. Though it orbits uncomfortably close to its star, the planet’s water may be kept liquid at 200° C by a dense, highly pressurized atmosphere. Not exactly a tropical paradise (though Dennis Overbye’s New York Times headline describes it as “sultry”), but easily the most Earthlike planet we’ve been able to characterize thus far.

Orbiting the red dwarf star GJ 1214 in the Ophiuchus constellation, the planet is also quite nearby by astronomical standards. At a distance of 42 light-years, it would still take several thousand lifetimes for us to get anything there, but its close proximity makes it an excellent target for ranged study by the James Webb Space Telescope scheduled to launch in 2014. In the meantime, the aging Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes may be used to study this bizarre waterworld.

Click on any banner to go to the post which won that prize:

Politics 2009

Philosophy 2009

Science 2009

It Denotes

If you walk by

And find me,

Lying on my side, curled

Like a comma

On a street corner

With no blanket

To cover myself

I am not in a coma

It denotes . . .

Stop briefly

And ponder over these times.

If you find me

Lying on my side

Legs stretched and straight

Head and shoulders

Bent forward, towards my loins

Like a question mark

It denotes . . .

Provide explanations . . .

Why certain people

Happen to sleep

On street pavements.

If you find me

Lying on my back

My whole body stretched

At a horizontal attention

like an exclamation mark

It denotes . . .

I am in shock

Do not bother

I will recover.

And when you find me coiled

My head between my legs

Round like a full stop

It denotes . . .

Stop and render first aid

Subject freezing.

by Julius Chingono

publisher: First published on PIW

in a special Zimbabwean edition,

10th June 2008, 2008

Walter Kirn in the New York Times Magazine:

In Limbo, where I’ve so often spent the holidays, I sat down last year in front of my computer on the night before the night before Christmas and tried to soothe my balsam-scented loneliness by reaching out to my newfound social network (“social networks” being what we have now in place of “friends and families”). Outside, in the streets of my snowy Montana hometown, noisy drinkers were strolling from bar to bar as I typed out the sad word “Facebook” on my keyboard and scanned my screen for familiar names and pictures. I didn’t find many for the simple reason that I was a novice at silicon socializing, and 90 percent of the people I knew on Facebook were people I didn’t know at all.

In Limbo, where I’ve so often spent the holidays, I sat down last year in front of my computer on the night before the night before Christmas and tried to soothe my balsam-scented loneliness by reaching out to my newfound social network (“social networks” being what we have now in place of “friends and families”). Outside, in the streets of my snowy Montana hometown, noisy drinkers were strolling from bar to bar as I typed out the sad word “Facebook” on my keyboard and scanned my screen for familiar names and pictures. I didn’t find many for the simple reason that I was a novice at silicon socializing, and 90 percent of the people I knew on Facebook were people I didn’t know at all.

More here.

Ronald Graham in American Scientist:

This impressive book represents an extremely ambitious and, I might add, highly successful attempt by Timothy Gowers and his coeditors, June Barrow-Green and Imre Leader, to give a current account of the subject of mathematics. It has something for nearly everyone, from beginning students of mathematics who would like to get some sense of what the subject is all about, all the way to professional mathematicians who would like to get a better idea of what their colleagues are doing.

This impressive book represents an extremely ambitious and, I might add, highly successful attempt by Timothy Gowers and his coeditors, June Barrow-Green and Imre Leader, to give a current account of the subject of mathematics. It has something for nearly everyone, from beginning students of mathematics who would like to get some sense of what the subject is all about, all the way to professional mathematicians who would like to get a better idea of what their colleagues are doing.

The 75-page introduction, which was written by Gowers, gives a very readable account of the basic branches of mathematics (algebra, geometry, analysis) and how these overlap and relate to one another, how they have developed and are continuing to do so, and how they are driven in large part by the types of questions mathematicians ask. This section should be mandatory reading for any prospective mathematics student.

Most of the articles that make up the rest of the book were written by leading experts. For example, Carl Pomerance has contributed a stimulating essay on computational number theory, Cliff Taubes provides a wonderful overview of differential topology, and Jordan Ellenberg gives a thoughtful summary of arithmetic geometry.

More here.

Richard Dawkins in Edge:

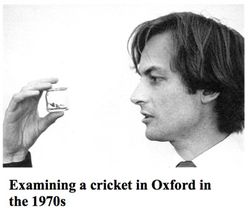

I should have been a child naturalist. I had every advantage: not only the perfect early environment of tropical Africa but what should have been the perfect genes to slot into it. For generations, sun-browned Dawkins legs have been striding in khaki shorts through the jungles of Empire. My Dawkins grandfather employed elephant lumberjacks in the teak forests of Burma. My father's maternal uncle, chief Conservator of Forests in Nepal, and his wife, author of a fearsome 'sporting' work called Tiger Lady, had a son who wrote the definitive handbooks on the Birds of Borneo and Birds of Burma. Like my father and his two younger brothers, I was all but born with a pith helmet on my head.

I should have been a child naturalist. I had every advantage: not only the perfect early environment of tropical Africa but what should have been the perfect genes to slot into it. For generations, sun-browned Dawkins legs have been striding in khaki shorts through the jungles of Empire. My Dawkins grandfather employed elephant lumberjacks in the teak forests of Burma. My father's maternal uncle, chief Conservator of Forests in Nepal, and his wife, author of a fearsome 'sporting' work called Tiger Lady, had a son who wrote the definitive handbooks on the Birds of Borneo and Birds of Burma. Like my father and his two younger brothers, I was all but born with a pith helmet on my head.

My father himself read Botany at Oxford, then became an agricultural officer in Nyasaland (now Malawi). During the war he was called up to join the army in Kenya, where I was born in 1941 and spent the first two years of my life. In 1943 my father was posted back to Nyasaland, where we lived until I was eight, when my parents and younger sister and I returned to England to live on the Oxfordshire farm that the Dawkins family had owned since 1726.

More here.

From MSNBC:

2009

50. Water on the moon: NASA sends a probe called Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite, or LCROSS, crashing into the moon. Weeks later, scientists report that an analysis of the impact debris confirms the existence of “significant” reserves of water ice. The mission followed up on indications from earlier probes (Clementine, Lunar Prospector, Chandrayaan 1, Cassini) and even from Apollo lunar samples. Some speculated that the findings could lead to a fresh round of lunar missions, but as the decade came to a close, NASA's plans for future exploration were still under review at the White House.

50. Water on the moon: NASA sends a probe called Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite, or LCROSS, crashing into the moon. Weeks later, scientists report that an analysis of the impact debris confirms the existence of “significant” reserves of water ice. The mission followed up on indications from earlier probes (Clementine, Lunar Prospector, Chandrayaan 1, Cassini) and even from Apollo lunar samples. Some speculated that the findings could lead to a fresh round of lunar missions, but as the decade came to a close, NASA's plans for future exploration were still under review at the White House.

For the rest of the 50-year timeline, you can revisit the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and 1990s separately, or see them all together on CASW's Web site.

Here are five more “Oh! Oh!” and “uh-oh” moments that are worth mentioning in a 10-year science review:

Oh! Oh! The International Space Station! The first expedition crew moves into the space station on Nov. 2, 2000, marking the beginning of full-time habitation that has continued for almost 10 years. The crew receives its first paying passenger in 2001 when millionaire investor Dennis Tito comes aboard. Six more have visited since then.

More here.

Steve Coll in The National:

If the American-led war in Afghanistan fails to contain the Taliban, it will not be for lack of resources or military talent; it will be because American leaders have failed to see and analyse the conflict’s diverse human terrain. Afghanistan may be known as a graveyard of empires but it is also a graveyard of generalisations. As the US Commanding General in Afghanistan, Stanley McChrystal, pointed out in his pessimistic assessment of the war last summer, international forces operating in Afghanistan have “not sufficiently studied Afghanistan’s peoples, whose needs, identities and grievances vary from province to province and from valley to valley”.

If the American-led war in Afghanistan fails to contain the Taliban, it will not be for lack of resources or military talent; it will be because American leaders have failed to see and analyse the conflict’s diverse human terrain. Afghanistan may be known as a graveyard of empires but it is also a graveyard of generalisations. As the US Commanding General in Afghanistan, Stanley McChrystal, pointed out in his pessimistic assessment of the war last summer, international forces operating in Afghanistan have “not sufficiently studied Afghanistan’s peoples, whose needs, identities and grievances vary from province to province and from valley to valley”.

The present American approach, derived from counterinsurgency doctrine, now presumes that political and economic tactics to pacify the Taliban will prove more effective than military force. But such a politics-first strategy, premised on forging a path toward negotiations with at least some Taliban elements, will require sharp eyesight about the Taliban’s strengths and weaknesses, as well as its place in Afghanistan’s social, tribal and cultural topography.

More here.

Saturday, December 19, 2009

Lewis Lapham in Lapham's Quarterly:

Lewis Lapham in Lapham's Quarterly:

This issue of Lapham’s Quarterly doesn’t trade in divine revelation, engage in theological dispute, or doubt the existence of God. What is of interest are the ways in which religious belief gives birth to historical event, makes law and prayer and politics, accounts for the death of an army or the life of a saint. Questions about the nature or substance of deity, whether it divides into three parts or seven, speaks Latin to the Romans, in tongues when traveling in Kentucky, I’ve learned over the last sixty-odd years to leave to sources more reliably informed. My grasp of metaphysics is as imperfect as my knowledge of Aramaic. I came to my early acquaintance with the Bible in company with my first readings of Grimm’s Fairy Tales and Bulfinch’s Mythology, but as an unbaptized child raised in a family unaffiliated with the teachings of a church, I missed the explanation as to why the stories about Moses and Jesus were to be taken as true while those about Apollo and Rumpelstiltskin were not.

Four years at Yale College in the 1950s rendered the question moot. It wasn’t that I’d missed the explanation; there was no explanation to miss, at least not one accessible by means other than the proverbial leap of faith. Then as now, the college was heavily invested in the proceeds of the Protestant Reformation, the testimony of God’s will being done present in the stonework of Harkness Tower and the cautionary ringing of its bells, as well as in the readings from scripture in Battell Chapel and the petitionings of Providence prior to the Harvard game. The college had been established in 1701 to bring a great light unto the gentiles in the Connecticut wilderness, the mission still extant 250 years later in the assigned study of Jonathan Edwards’ sermons and John Donne’s verse. Nowhere in the texts did I see anything other than words on paper—very beautiful words but not the living presence to which they alluded in rhyme royal and iambic pentameter. I attributed the failure to the weakness of my imagination and my poor performance at both the pole vault and the long jump.

I brought the same qualities into the apostate lecture halls where it was announced that God was dead. The time and cause of death were variously given in sophomore and senior surveys of western civilization—disemboweled by Machiavelli in sixteenth-century Florence, assassinated in eighteenth-century Paris by agents of the French Enlightenment, lost at sea in 1835 while on a voyage with Charles Darwin to the Galapagos Islands, garroted by Friedrich Nietzsche on a Swiss Alp in the autumn of 1882, disappeared into the nuclear cloud ascending from Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. The assisting coroners attached to one or another of the history faculties submitted densely footnoted autopsy reports, but none of the lab work brought forth a thumbprint of the deceased.

Over at Ex-Berliner, Jacinta Nandi on a conversation she has with her ex:

Over at Ex-Berliner, Jacinta Nandi on a conversation she has with her ex:

My ex came over yesterday and I asked him what he thought about the Minaretten-Verbot.

“What Minaretten-Verbot?” He asked.

“You know,” I said, “the Swiss people holding a referendum and deciding to ban minarettes on their towers for no other reason than being totally fucking racist.”

“Not everything is racist, Jacinta,” he said carefully. “You think everything is racist? But a referendum can't be racist – it's the people's decision. The people have decided.”

The thing is, in German the word for referendum is Volksentscheid, the people's decision, so what he said made a bit more sense in German, but I'll be honest, okay, I was looking at him and thinking about trains headed in the direction of Poland.

“Unless the people decide something racist….” I said.

He laughed, then. “It's up to the Swiss to decide,” he said. “Maybe they really hate those funny-looking little towers.”

Johann Hari in CommonDreams.org:

Discarded Idea Three: Climate debt. The rich world has been responsible for 70 per cent of the warming gases in the atmosphere – yet 70 per cent of the effects are being felt in the developing world. Holland can build vast dykes to prevent its land flooding; Bangladesh can only drown. There is a cruel inverse relationship between cause and effect: the polluter doesn't pay.

So we have racked up a climate debt. We broke it; they paid. At this summit, for the first time, the poor countries rose in disgust. Their chief negotiator pointed out that the compensation offered “won't even pay for the coffins”. The cliché that environmentalism is a rich person's ideology just gasped its final CO2-rich breath. As Naomi Klein put it: “At this summit, the pole of environmentalism has moved south.”

When we are dividing up who has the right to emit the few remaining warming gases that the atmosphere can absorb, we need to realise that we are badly overdrawn. We have used up our share of warming gases, and then some. Yet the US and EU have dismissed the idea of climate debt out of hand. How can we get a lasting deal that every country agrees to if we ignore this basic principle of justice? Why should the poorest restrain themselves when the rich refuse to?

A deal based on these real ideas would actually cool the atmosphere. The alternatives championed at Copenhagen by the rich world – carbon offsetting, carbon trading, carbon capture – won't. They are a global placebo.

Amy Rosenberg in The National:

And then I began to notice that other Indian novelists I met and read about, and writers from other former British colonies (and from Japan, France, Germany, Holland and, of course, Britain itself) also talked often about Blyton, and that they underwent similar transformations whenever they did. They displayed intense nostalgia, as if they’d actually visited the worlds Blyton had created, and they knew they could never return. I heard them saying that, more than any other writer, Blyton had exposed them to the pleasures of fiction. For many, she opened up the English language, saturating the dry lessons learnt in school. She brought them inside an idealised world, the world of the former conquerors; in a funny kind of reversal, that world seemed as exotic as it did quixotic. Kids owned their own islands, ate Christmas goose for dinner, slept outdoors in fields of heather and explored moors and gorse and rocky shores. For a kid, especially a lower-middle class kid, from Calcutta, Delhi or smaller urban centres in India or other parts of the former empire, how could you get more exotic than that?

And then I began to notice that other Indian novelists I met and read about, and writers from other former British colonies (and from Japan, France, Germany, Holland and, of course, Britain itself) also talked often about Blyton, and that they underwent similar transformations whenever they did. They displayed intense nostalgia, as if they’d actually visited the worlds Blyton had created, and they knew they could never return. I heard them saying that, more than any other writer, Blyton had exposed them to the pleasures of fiction. For many, she opened up the English language, saturating the dry lessons learnt in school. She brought them inside an idealised world, the world of the former conquerors; in a funny kind of reversal, that world seemed as exotic as it did quixotic. Kids owned their own islands, ate Christmas goose for dinner, slept outdoors in fields of heather and explored moors and gorse and rocky shores. For a kid, especially a lower-middle class kid, from Calcutta, Delhi or smaller urban centres in India or other parts of the former empire, how could you get more exotic than that?

More here.

One of life’s oddities is how often a series of genuinely comedic incidents congeals into, if not tragedy, then tragic loss. Robert Sellers certainly has no intention of turning readers’ thoughts in that moody direction, but “Hellraisers: The Life and Inebriated Times of Richard Burton, Richard Harris, Peter O’Toole and Oliver Reed” probably will, though there’s a tremendous amount of unapologetic, unself-conscious fun to be had on the way to introspection. Burton, Harris, O’Toole and Reed were four of the great actors to emerge in postwar British stage and cinema; they also were legendary drunks, who not only pursued their avocation — it surely was more than a recreation — in public and without regrets. Today, when what we used to term a “hard drinker” is routinely referred to as a “high-functioning alcoholic,” it’s difficult to imagine an account of their lives free of judgment or amateur psychoanalysis. Sellers, a drama school grad and former London stand-up comic-turned-film writer and pop culture critic, manages to pull it off. It may be, in fact, that he just loves a great series of stories about fascinatingly intelligent and preternaturally talented men behaving in utterly outrageous ways.

more from Tim Rutten at the LAT here.

Avishai Margalit in the NYRB blog:

Avishai Margalit in the NYRB blog:

For a war to be just, there must be moral grounds for going to war and moral conduct in the war. Thus, going to war requires having a just cause, whereas correct behavior in the war requires discriminating between combatants and civilians. Obama mentioned both conditions as well as some others. But then there are also conditions that must be met for continuing a war, among them having a reasonable prospect of success. Yet in his Nobel speech, Obama omitted this important condition for continuing the war in Afghanistan. It is not only stupid, but it is also immoral, to go to war, or to continue a war, when there is no prospect of victory. Having the right cause on your side is not enough; your chances of winning are just as important.

As an admirer of President Obama I have listened attentively to his recent speeches on Afghanistan. But at no point has he made a plausible case for how he will win the war. He counts on our taking a leap of faith to support his strategy, but leaps should be reserved for frogs, whereas we should subject our faith to critical thinking.

The main declared objective of the war—defeating al-Qaeda—is not a matter for helmeted marines but for bespectacled bank accountants, computer whiz-kids, and people who can speak the relevant languages. The war in Afghanistan, by now, has very little to do with defeating al-Qaeda. Vice President Joe Biden got it right when he argued that fighting al-Qaeda is not the same thing as fighting in Afghanistan. Moreover, the conflict in Afghanistan bears little relevance to the problem of keeping Pakistan’s nuclear weapons out of the hands of radical Islamists; the Pakistani army is as much of a problem as the Taliban.

Adhering to just war doctrine requires having the right intent for continuing to fight in Afghanistan. Continuing the war out of fear of being accused of not giving the generals the resources they need to finish the job does not count as the right intent.

Paul Krugman in the New York Times:

Yes, the filibuster-imposed need to get votes from “centrist” senators has led to a bill that falls a long way short of ideal. Worse, some of those senators seem motivated largely by a desire to protect the interests of insurance companies — with the possible exception of Mr. Lieberman, who seems motivated by sheer spite.

Yes, the filibuster-imposed need to get votes from “centrist” senators has led to a bill that falls a long way short of ideal. Worse, some of those senators seem motivated largely by a desire to protect the interests of insurance companies — with the possible exception of Mr. Lieberman, who seems motivated by sheer spite.

But let’s all take a deep breath, and consider just how much good this bill would do, if passed — and how much better it would be than anything that seemed possible just a few years ago. With all its flaws, the Senate health bill would be the biggest expansion of the social safety net since Medicare, greatly improving the lives of millions. Getting this bill would be much, much better than watching health care reform fail.

At its core, the bill would do two things. First, it would prohibit discrimination by insurance companies on the basis of medical condition or history: Americans could no longer be denied health insurance because of a pre-existing condition, or have their insurance canceled when they get sick. Second, the bill would provide substantial financial aid to those who don’t get insurance through their employers, as well as tax breaks for small employers that do provide insurance.

More here.

Morgan Meis in The Smart Set:

Morgan Meis in The Smart Set:

Every 10 years or so, Heidegger's Nazism bursts into public consciousness again. Often, this happens with the publication of a book. The most cataclysmic of these bursts was probably the publication of Victor Farías' Heidegger and Nazism, in 1987. Farías' book took the Nazi accusations to a new level. Previously, it had been possible to discuss Heidegger's Nazism as a political misstep, the naïve blunderings of a philosopher trying to deal with the real world. Farías showed that the relationship was far deeper, that Heidegger's thinking was infected with Nazi thinking and that Heidegger was well aware of that fact. Admirers of Heidegger accused Farías of oversimplifying and conducting a witch hunt. Fancy persons in France wrote elegant essays explaining the importance of Heidegger's thought and the infinite complexity of the relation between thought and politics.

A boring war raged on for decades. But let us be honest, friends — Farías was more or less correct. Over time, the fact of Heidegger's Nazism and its integral relationship to his thinking has sunk in. This brings us to the present, and to the English-language publication of Emmanuel Faye's Heidegger: The Introduction of Nazism into Philosophy. If Farías provided the nails to Heidegger's coffin, Faye has come along in the role of Big Hammer. Carl Romano, in his essay “Heil Heidegger!” in The Chronicle Review, sums up the situation following the publication of Faye's book with the following:

How many scholarly stakes in the heart will we need before Martin Heidegger (1889-1976), still regarded by some as Germany's greatest 20th-century philosopher, reaches his final resting place as a prolific, provincial Nazi hack? Overrated in his prime, bizarrely venerated by acolytes even now, the pretentious old Black Forest babbler makes one wonder whether there's a university-press equivalent of wolfsbane, guaranteed to keep philosophical frauds at a distance.

The coffin is sealed.

This is an ambitious portrait of an American legend. Ray Robinson was not just a prizefighter. He was an extraordinary fighter. Someone once said: “There was Ray Robinson. And then there were the top 10.” He was certainly the greatest prizefighter I ever saw. But Wil Haygood has written more than a simple chronicle of a sports career. He wants to place Robinson as a central figure in the rise of urban African-Americans in the 20th century. At the peak of his success, in the 1940s and ’50s, Robinson epitomized the tough grace and style and confidence of an entire generation. He would display those qualities all over the United States and Europe. Haygood chooses to tell this tale, in part, as a kind of prose ballad. In lyrical language, he traces the life of Robinson from his birth in Detroit in 1921 as Walker Smith Jr. to his truest home, in Harlem, on the great glittering island of Manhattan, to California, where he died in 1989.

more from Pete Hamill at the NYT here.

Evan Lerner in Seed Magazine: