Michael Wood in LRB:

If you had asked me a month ago I would have said I didn’t believe in heroes. I realise now that there have been people in my life – Edward, the above-mentioned Fred Dupee, my Cambridge teacher and friend Peter Stern, and my father – who represented ideal forms of what a person could be. They were, variously, models of intelligence, persistence, courage, delicacy, honour, depth of argument, decency, kindness, much else. One can speak to such models mentally even though they are dead, and one can imagine their responses. One can write sentences, even books, for them, and benefit from the memory of the risk and rigour of their thought. But there is still something desolate about their absence from the world. For one thing, they won’t make new arguments or comments; for another, no one younger will get to know them, learn of the exemplary possibilities these people proposed.

If you had asked me a month ago I would have said I didn’t believe in heroes. I realise now that there have been people in my life – Edward, the above-mentioned Fred Dupee, my Cambridge teacher and friend Peter Stern, and my father – who represented ideal forms of what a person could be. They were, variously, models of intelligence, persistence, courage, delicacy, honour, depth of argument, decency, kindness, much else. One can speak to such models mentally even though they are dead, and one can imagine their responses. One can write sentences, even books, for them, and benefit from the memory of the risk and rigour of their thought. But there is still something desolate about their absence from the world. For one thing, they won’t make new arguments or comments; for another, no one younger will get to know them, learn of the exemplary possibilities these people proposed.

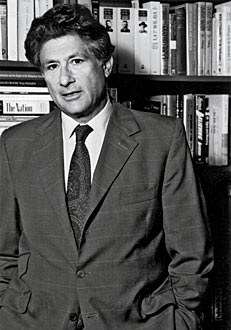

Edward was a dapper dresser, and he liked people to pay attention to such things – for their own sake, and because he liked the idea of style. I think perhaps the first conversation we ever had – this would have been some time in the autumn of 1964, I had just arrived at Columbia and Edward had started there the year before – was about a smart jacket (or jackets) he had bought downtown, maybe at Barney’s but probably somewhere posher. He insisted I go and get one of these items because the price was so fantastic, and he asked me every day whether I’d been yet. I didn’t need (and couldn’t afford) a jacket, but I couldn’t withstand the force of Edward’s solicitude, and finally went and bought one. Black. Cashmere. Very nice. I wore it for ages. Edward’s affection enveloped you like a roar, like a cure – even when he became the one who was ill. You felt better every time you saw him. Or rather, you felt you could be better than you were, and you thought the world was a larger place than it had seemed before.

More here. (Note: This post is also in honor of Professor Edward Said's seventh death anniversary today)