Hannah Critchlow in The Guardian:

Since the sequencing of the human genome in 2003, genetics has become one of the key frameworks for how we all think about ourselves. From fretting about our health to debating how schools can accommodate non-neurotypical pupils, we reach for the idea that genes deliver answers to intimate questions about people’s outcomes and identities. Recent research backs this up, showing that complex traits such as temperament, longevity, resilience to mental ill-health and even ideological leanings are all, to some extent, “hardwired”. Environment matters too for these qualities, of course. Our education and life experiences interact with genetic factors to create a fantastically complex matrix of influence. But what if the question of genetic inheritance were even more nuanced? What if the old polarised debate about the competing influences of nature and nurture was due a 21st-century upgrade?

Since the sequencing of the human genome in 2003, genetics has become one of the key frameworks for how we all think about ourselves. From fretting about our health to debating how schools can accommodate non-neurotypical pupils, we reach for the idea that genes deliver answers to intimate questions about people’s outcomes and identities. Recent research backs this up, showing that complex traits such as temperament, longevity, resilience to mental ill-health and even ideological leanings are all, to some extent, “hardwired”. Environment matters too for these qualities, of course. Our education and life experiences interact with genetic factors to create a fantastically complex matrix of influence. But what if the question of genetic inheritance were even more nuanced? What if the old polarised debate about the competing influences of nature and nurture was due a 21st-century upgrade?

Scientists working in the emerging field of epigenetics have discovered the mechanism that allows lived experience and acquired knowledge to be passed on within one generation, by altering the shape of a particular gene. This means that an individual’s life experience doesn’t die with them but endures in genetic form. The impact of the starvation your Dutch grandmother suffered during the second world war, for example, or the trauma inflicted on your grandfather when he fled his home as a refugee, might go on to shape your parents’ brains, their behaviours and eventually yours.

More here.

Don’t mellow my harsh, dude.

Don’t mellow my harsh, dude. Netflix’s Baby Reindeer became an instant hit with viewers after it debuted earlier in April, with

Netflix’s Baby Reindeer became an instant hit with viewers after it debuted earlier in April, with  G

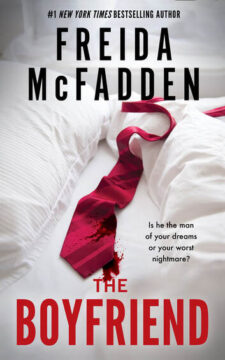

G When Freida McFadden self-published her first novel, “The Devil Wears Scrubs,” more than a decade ago, she figured it would mark both the start and the end of her literary career.

When Freida McFadden self-published her first novel, “The Devil Wears Scrubs,” more than a decade ago, she figured it would mark both the start and the end of her literary career. But I’d wager that if you wanted to see the most exciting drama happening at the MGM on this Friday night, you’d have to walk through the casino and look for the small sign advertising something called The Active Cell. This is the site of the play-in round for the Excel World Championship, and it starts in five minutes. There are 27 people here to take part in this event (28 registered, but one evidently chickened out before we started), which will send its top eight finishers to tomorrow night’s finals. There, one person will be crowned the Excel World Champion, which comes with a trophy and a championship belt and the ability to spend the next 12 months bragging about being officially the world’s best spreadsheeter. Eight people have already qualified for the finals; some of today’s 27 contestants lost in those qualifying rounds, others just showed up last-minute in hopes of a comeback.

But I’d wager that if you wanted to see the most exciting drama happening at the MGM on this Friday night, you’d have to walk through the casino and look for the small sign advertising something called The Active Cell. This is the site of the play-in round for the Excel World Championship, and it starts in five minutes. There are 27 people here to take part in this event (28 registered, but one evidently chickened out before we started), which will send its top eight finishers to tomorrow night’s finals. There, one person will be crowned the Excel World Champion, which comes with a trophy and a championship belt and the ability to spend the next 12 months bragging about being officially the world’s best spreadsheeter. Eight people have already qualified for the finals; some of today’s 27 contestants lost in those qualifying rounds, others just showed up last-minute in hopes of a comeback. Bird flu poses a massive threat, and the potential for a catastrophic new pandemic is imminent. We still have a chance to stop a possible humanitarian disaster, but only if we get to work urgently, carefully and aggressively.

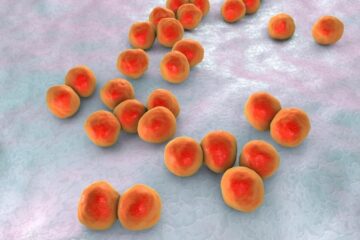

Bird flu poses a massive threat, and the potential for a catastrophic new pandemic is imminent. We still have a chance to stop a possible humanitarian disaster, but only if we get to work urgently, carefully and aggressively. Stepping into High Ceiling and dimly lit Irani cafes with vintage furniture, mosaic chipped floors and tablecloths take one back to old Karachi. These desolate Irani cafes were once hubs of social and intellectual exchange and frequented by students, journalists, and intellectuals.

Stepping into High Ceiling and dimly lit Irani cafes with vintage furniture, mosaic chipped floors and tablecloths take one back to old Karachi. These desolate Irani cafes were once hubs of social and intellectual exchange and frequented by students, journalists, and intellectuals. Last year marked the fiftieth anniversary of Strauss’s death. With the notable exception of a tribute by the (now retired) Harvard professor Harvey C. Mansfield in the

Last year marked the fiftieth anniversary of Strauss’s death. With the notable exception of a tribute by the (now retired) Harvard professor Harvey C. Mansfield in the  Despite their small size,

Despite their small size,