A.O. Scott at the NYT:

Its canonical status is hardly in doubt, but at the same time, 20 years after its publication, “The Known World” can still feel like a discovery. Even a rereading propels you into uncharted territory. You may think you know about American slavery, about the American novel, about the American slavery novel, but here is something you couldn’t have imagined, a secret history hidden in plain sight. The author occupies a similarly paradoxical status: He’s a major writer, yet somehow underrecognized. This may be partly because he doesn’t call much attention to himself, and partly because of his compact output. (When I asked, he said he wasn’t working on anything new at the moment, though there was a story that had been gestating for a while.) Jones, who teaches creative writing at George Washington University, is not a recluse, but he’s not a public figure either. Our meeting place was his idea.

Its canonical status is hardly in doubt, but at the same time, 20 years after its publication, “The Known World” can still feel like a discovery. Even a rereading propels you into uncharted territory. You may think you know about American slavery, about the American novel, about the American slavery novel, but here is something you couldn’t have imagined, a secret history hidden in plain sight. The author occupies a similarly paradoxical status: He’s a major writer, yet somehow underrecognized. This may be partly because he doesn’t call much attention to himself, and partly because of his compact output. (When I asked, he said he wasn’t working on anything new at the moment, though there was a story that had been gestating for a while.) Jones, who teaches creative writing at George Washington University, is not a recluse, but he’s not a public figure either. Our meeting place was his idea.

more here.

The Earth’s oceans remain a source of anxious uncertainty. For all that we’ve chartered upon the waves of the sea, that which lies beneath remains as dark as the impenetrable barriers through which surface light does not penetrate, a black kingdom of translucent glowing fish with jagged deaths-teeth and of massive worms living in volcanic trenches. More than even interstellar space, the ocean’s uncanniness disrupts because the entrance to this unknown empire is as near as the closest beach, where even on the sunniest days a consideration of what hides below can give a sense of what the horror author H.P. Lovecraft wrote in a 1927 essay from The Recluse, when he claimed that the “oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is a fear of the unknown.” The conjuring of that emotion was a motivating impulse in Lovecraft’s weird fiction, in which he imagined such horrors as the “elder god” Cthulhu, a massive, uncaring, and nearly immortal alien cephalopod imprisoned in the ancient sunken city of R’lyeh, located approximately 50 degrees south and 100 degrees west.

The Earth’s oceans remain a source of anxious uncertainty. For all that we’ve chartered upon the waves of the sea, that which lies beneath remains as dark as the impenetrable barriers through which surface light does not penetrate, a black kingdom of translucent glowing fish with jagged deaths-teeth and of massive worms living in volcanic trenches. More than even interstellar space, the ocean’s uncanniness disrupts because the entrance to this unknown empire is as near as the closest beach, where even on the sunniest days a consideration of what hides below can give a sense of what the horror author H.P. Lovecraft wrote in a 1927 essay from The Recluse, when he claimed that the “oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is a fear of the unknown.” The conjuring of that emotion was a motivating impulse in Lovecraft’s weird fiction, in which he imagined such horrors as the “elder god” Cthulhu, a massive, uncaring, and nearly immortal alien cephalopod imprisoned in the ancient sunken city of R’lyeh, located approximately 50 degrees south and 100 degrees west. The inspiration for the titular device in last year’s blockbuster,

The inspiration for the titular device in last year’s blockbuster,  It can be a comfort and consolation to believe one’s political opponents don’t really mean what they say. They’re liars. Hypocrites. Shameless opportunists who will say and do anything to gain power. It’s impossible to take them seriously.

It can be a comfort and consolation to believe one’s political opponents don’t really mean what they say. They’re liars. Hypocrites. Shameless opportunists who will say and do anything to gain power. It’s impossible to take them seriously. W

W T

T Henry Grabar has had enough

Henry Grabar has had enough  THERE ARE SOME things the American mind can’t fully grasp: a certain way of smoking a cigarette, a particular fit of track pant, Rita Ora as a genuine celebrity. But above all, we struggle with the reality that the largest cultural event in the world happens entirely off of our radar and outside of our influence. The

THERE ARE SOME things the American mind can’t fully grasp: a certain way of smoking a cigarette, a particular fit of track pant, Rita Ora as a genuine celebrity. But above all, we struggle with the reality that the largest cultural event in the world happens entirely off of our radar and outside of our influence. The Vivian Maier took more than 150,000 photographs as she scoured the streets of New York and Chicago. She

Vivian Maier took more than 150,000 photographs as she scoured the streets of New York and Chicago. She  For many, AI helps fuel a faith that technology will deliver us from ecological disaster, even as that disaster takes hold. This techno-optimism is often framed as the foe of the “ecological turn”—a constellation of beliefs that instead see salvation in living more ecologically, as a part of nature.

For many, AI helps fuel a faith that technology will deliver us from ecological disaster, even as that disaster takes hold. This techno-optimism is often framed as the foe of the “ecological turn”—a constellation of beliefs that instead see salvation in living more ecologically, as a part of nature. Unlike the many members of the left who captivated him as a young man — such as Dwight Macdonald, George Orwell, and Bertrand Russell — Noam Chomsky himself did not come to left-libertarian or anarchist thinking as a result of his disillusionment with liberal thought. He quite literally started there. At a tender age, he had begun his search for information on contemporary left-libertarian movements, and did not abandon it. Among those figures he was drawn to, George Orwell is especially fascinating, both because of the impact that he had on a broad spectrum of society and the numerous contacts and acquaintances he had in the libertarian left. Chomsky refers to Orwell frequently in his political writings, and when one reads Orwell’s works, the reasons for his attraction to someone interested in the Spanish Civil War from an anarchist perspective become clear.

Unlike the many members of the left who captivated him as a young man — such as Dwight Macdonald, George Orwell, and Bertrand Russell — Noam Chomsky himself did not come to left-libertarian or anarchist thinking as a result of his disillusionment with liberal thought. He quite literally started there. At a tender age, he had begun his search for information on contemporary left-libertarian movements, and did not abandon it. Among those figures he was drawn to, George Orwell is especially fascinating, both because of the impact that he had on a broad spectrum of society and the numerous contacts and acquaintances he had in the libertarian left. Chomsky refers to Orwell frequently in his political writings, and when one reads Orwell’s works, the reasons for his attraction to someone interested in the Spanish Civil War from an anarchist perspective become clear. If ever there was ‘an individual who has a high intellectual potential’, Sontag was it. She was reading Thomas Mann aged eleven, matriculated at Berkeley at fifteen and was writing essays of superlative, inspirational elegance and density by her late twenties. Being intelligent – being more intelligent than anyone else – was not just important to Sontag: it was the thing she needed her mosaic to depict. The cultural critic Mark Greif, who knew her late in her life, said that ‘Susan made you acknowledge that she was more intelligent than you. She then compelled you to admit that she felt more than you did.’ Sontag may have ‘felt more’ than other people – certainly, she swore that her life’s work was ‘to see more, to feel more, to think more’. But there is considerable evidence actually that she spent her life refusing to feel – refusing, that is, to feel vulnerable. She had been vulnerable as a child; she never accepted this, and never got over it.

If ever there was ‘an individual who has a high intellectual potential’, Sontag was it. She was reading Thomas Mann aged eleven, matriculated at Berkeley at fifteen and was writing essays of superlative, inspirational elegance and density by her late twenties. Being intelligent – being more intelligent than anyone else – was not just important to Sontag: it was the thing she needed her mosaic to depict. The cultural critic Mark Greif, who knew her late in her life, said that ‘Susan made you acknowledge that she was more intelligent than you. She then compelled you to admit that she felt more than you did.’ Sontag may have ‘felt more’ than other people – certainly, she swore that her life’s work was ‘to see more, to feel more, to think more’. But there is considerable evidence actually that she spent her life refusing to feel – refusing, that is, to feel vulnerable. She had been vulnerable as a child; she never accepted this, and never got over it. Nearly half of all Americans struggle to afford access to quality health care and prescription medications. This is the warning of the latest report from the Healthcare Affordability Index, which tracks how many in the U.S. have been forced to avoid medical care or haven’t been able to fill their prescriptions in the last three months—and how many would struggle to pay for care if it was needed. Affordability has fallen six points since 2022, down to a record low of 55 percent since the index was launched back in 2021. According to the researchers, this descent mainly affects two age groups: those aged 50–64 (down eight points to 55 percent over the same period) and those 65 and older (down eight points to 71 percent).

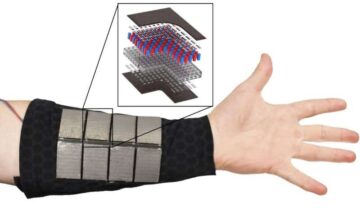

Nearly half of all Americans struggle to afford access to quality health care and prescription medications. This is the warning of the latest report from the Healthcare Affordability Index, which tracks how many in the U.S. have been forced to avoid medical care or haven’t been able to fill their prescriptions in the last three months—and how many would struggle to pay for care if it was needed. Affordability has fallen six points since 2022, down to a record low of 55 percent since the index was launched back in 2021. According to the researchers, this descent mainly affects two age groups: those aged 50–64 (down eight points to 55 percent over the same period) and those 65 and older (down eight points to 71 percent). In the age of technology everywhere, we are all too familiar with the inconvenience of a dead battery. But for those relying on a wearable health care device to monitor glucose, reduce tremors, or even track heart function, taking time to recharge can pose a big risk.

In the age of technology everywhere, we are all too familiar with the inconvenience of a dead battery. But for those relying on a wearable health care device to monitor glucose, reduce tremors, or even track heart function, taking time to recharge can pose a big risk. Elaine Scarry lives in a pale pink house near the Charles River in Cambridge, Massachusetts. A tall hedge runs along the front, rising to the second story and nearly engulfing the white picket gate through which one passes into Scarry’s garden. Flowers thrive in dense beds overlooked by crabapple trees and yews. Toward the back of the house, a curved wall of windows divides the garden from the garden room. Scarry’s longtime partner, the writer and scholar Philip Fisher, keeps a house nearby and they split their time between the two. Fisher does the cooking, and they eat dinner at his place. When it’s nice out they like to go for a drive.

Elaine Scarry lives in a pale pink house near the Charles River in Cambridge, Massachusetts. A tall hedge runs along the front, rising to the second story and nearly engulfing the white picket gate through which one passes into Scarry’s garden. Flowers thrive in dense beds overlooked by crabapple trees and yews. Toward the back of the house, a curved wall of windows divides the garden from the garden room. Scarry’s longtime partner, the writer and scholar Philip Fisher, keeps a house nearby and they split their time between the two. Fisher does the cooking, and they eat dinner at his place. When it’s nice out they like to go for a drive.