Jason Dorrier in Singularity Hub:

Computer chips are a hot commodity. Nvidia is now one of the most valuable companies in the world, and the Taiwanese manufacturer of Nvidia’s chips, TSMC, has been called a geopolitical force. It should come as no surprise, then, that a growing number of hardware startups and established companies are looking to take a jewel or two from the crown.

Computer chips are a hot commodity. Nvidia is now one of the most valuable companies in the world, and the Taiwanese manufacturer of Nvidia’s chips, TSMC, has been called a geopolitical force. It should come as no surprise, then, that a growing number of hardware startups and established companies are looking to take a jewel or two from the crown.

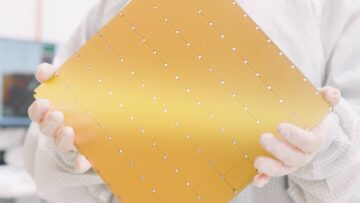

Of these, Cerebras is one of the weirdest. The company makes computer chips the size of tortillas bristling with just under a million processors, each linked to its own local memory. The processors are small but lightning quick as they don’t shuttle information to and from shared memory located far away. And the connections between processors—which in most supercomputers require linking separate chips across room-sized machines—are quick too.

This means the chips are stellar for specific tasks. Recent preprint studies in two of these—one simulating molecules and the other training and running large language models—show the wafer-scale advantage can be formidable. The chips outperformed Frontier, the world’s top supercomputer, in the former. They also showed a stripped down AI model could use a third of the usual energy without sacrificing performance.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

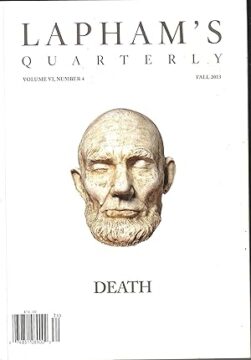

It is dangerous to excel at two different things. You run the risk of being underappreciated in one or the other; think of Michelangelo as a poet, of Michael Jordan as a baseball player. This is a trap that Lewis Lapham has largely avoided. For the past half century, he has been getting pretty much equal esteem in a pair of distinct roles: editor and essayist. As an editor, he is hailed for his three-decade career at the helm of Harper’s, America’s second-oldest magazine, which he reinvigorated in 1983; and then, as an encore a decade ago, for Lapham’s Quarterly, a wholly new kind of periodical in his own intellectual image. As an essayist, he was called “without a doubt our greatest satirist” by Kurt Vonnegut.

It is dangerous to excel at two different things. You run the risk of being underappreciated in one or the other; think of Michelangelo as a poet, of Michael Jordan as a baseball player. This is a trap that Lewis Lapham has largely avoided. For the past half century, he has been getting pretty much equal esteem in a pair of distinct roles: editor and essayist. As an editor, he is hailed for his three-decade career at the helm of Harper’s, America’s second-oldest magazine, which he reinvigorated in 1983; and then, as an encore a decade ago, for Lapham’s Quarterly, a wholly new kind of periodical in his own intellectual image. As an essayist, he was called “without a doubt our greatest satirist” by Kurt Vonnegut.

One of this year’s most influential people on TikTok and YouTube does not see himself as an influencer. He is Thích Minh Tuệ, a middle-aged man who adopted a humble, ascetic life a few years ago and began to walk barefoot up and down Vietnam. He lived in forests with few clothes and accepted alms from strangers, practicing a Buddhist way of frugal simplicity. In May, he became an internet phenomenon. Admirers began to post videos of him along his pilgrimage, inspiring millions. While disavowing any attempt at virtue signaling, he nonetheless was widely seen as an exemplary model, especially in comparison with the lavish lifestyles of top officials. Vietnamese were particularly irked when the minister of public security was caught on camera eating gold-encrusted steak at a London restaurant three years ago. In June, at the strong advice of police, Thích Minh Tuệ disappeared from public view. “His real crime was his humble lifestyle that stands in such stark contrast to the corruption scandals that have rocked Vietnam,” wrote Zachary Abuza, professor at the National War College in Washington, for Radio Free Asia.

One of this year’s most influential people on TikTok and YouTube does not see himself as an influencer. He is Thích Minh Tuệ, a middle-aged man who adopted a humble, ascetic life a few years ago and began to walk barefoot up and down Vietnam. He lived in forests with few clothes and accepted alms from strangers, practicing a Buddhist way of frugal simplicity. In May, he became an internet phenomenon. Admirers began to post videos of him along his pilgrimage, inspiring millions. While disavowing any attempt at virtue signaling, he nonetheless was widely seen as an exemplary model, especially in comparison with the lavish lifestyles of top officials. Vietnamese were particularly irked when the minister of public security was caught on camera eating gold-encrusted steak at a London restaurant three years ago. In June, at the strong advice of police, Thích Minh Tuệ disappeared from public view. “His real crime was his humble lifestyle that stands in such stark contrast to the corruption scandals that have rocked Vietnam,” wrote Zachary Abuza, professor at the National War College in Washington, for Radio Free Asia.

Drinking even small amounts of alcohol reduces your life expectancy, rigorous studies show. Only those with serious flaws suggest that

Drinking even small amounts of alcohol reduces your life expectancy, rigorous studies show. Only those with serious flaws suggest that

W

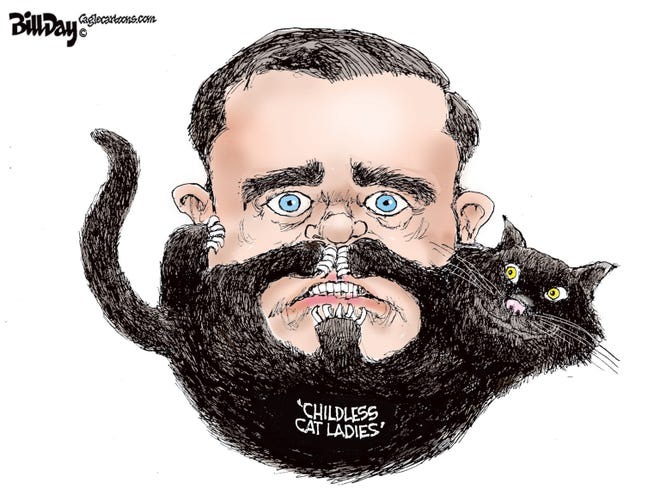

W The man who may very well become the vice-president of the US

The man who may very well become the vice-president of the US  It sounded like the right thing to do. I was a first-year Ph.D. student in educational psychology, and my research adviser told me I should consider practicing open science—“being open and above board,” as he put it. He suggested I make my first-year research project a preregistered report. We would publish our planned methods and analysis in advance, an approach meant to minimize questionable research practices such as cherry-picking of results. I found myself at a crossroads. On one hand, the promise of enhancing transparency and reproducibility was compelling. On the other, I was frightened about potential negative repercussions.

It sounded like the right thing to do. I was a first-year Ph.D. student in educational psychology, and my research adviser told me I should consider practicing open science—“being open and above board,” as he put it. He suggested I make my first-year research project a preregistered report. We would publish our planned methods and analysis in advance, an approach meant to minimize questionable research practices such as cherry-picking of results. I found myself at a crossroads. On one hand, the promise of enhancing transparency and reproducibility was compelling. On the other, I was frightened about potential negative repercussions.