Matthew Sparkes in New Scientist:

Drivers on a busy US freeway have been controlled by an AI since March, as part of a study that has put a machine-learning system in charge of setting variable speed limits on the road. The impact on efficiency and driver safety is unclear, as researchers are still analysing the results.

Drivers on a busy US freeway have been controlled by an AI since March, as part of a study that has put a machine-learning system in charge of setting variable speed limits on the road. The impact on efficiency and driver safety is unclear, as researchers are still analysing the results.

Roads with variable speed limits, also known as smart motorways, are common in countries including the US, UK and Germany. Normally, rule-based systems monitor the number of vehicles on one of these roads and adjust speeds accordingly. One such road is a 27-kilometre section of the I-24 freeway near Nashville, Tennessee, which was experiencing a problem that besets many busy roads: when there are too many vehicles, phantom traffic jams appear when drivers brake, slowing vehicles to a crawl and risking crashes as fast-moving vehicles come up behind.

To address this, Daniel Work at Vanderbilt University in Nashville and his colleagues trained an AI on historical traffic data to monitor cameras and make decisions on speed limits, deploying it in the I-24 control room in February.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Transnational organized crime is a paradox: ubiquitous yet invisible. While criminal tactics evolve rapidly, government-led responses are often static. When criminal networks are squeezed in one jurisdiction, they rapidly balloon in another. Although the problem concerns everyone, it is often considered too sensitive to discuss at the national, much less the global, level. As a result, the international community – including the United Nations and its member states –

Transnational organized crime is a paradox: ubiquitous yet invisible. While criminal tactics evolve rapidly, government-led responses are often static. When criminal networks are squeezed in one jurisdiction, they rapidly balloon in another. Although the problem concerns everyone, it is often considered too sensitive to discuss at the national, much less the global, level. As a result, the international community – including the United Nations and its member states –  My family history of cancer is impressive, and not in a good way.

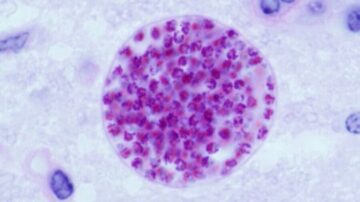

My family history of cancer is impressive, and not in a good way. The brain is like a medieval castle perched on a cliff, protected on all sides by high walls, making it nearly impenetrable. Its shield is the blood-brain barrier, a layer of tightly connected cells that only allows an extremely selective group of molecules to pass. The barrier keeps delicate brain cells safely away from harmful substances, but it also blocks therapeutic proteins—like, for example, those that grab onto and neutralize toxic clumps in Alzheimer’s disease. One way to smuggle proteins across? A cat parasite. A

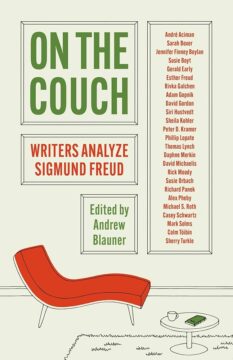

The brain is like a medieval castle perched on a cliff, protected on all sides by high walls, making it nearly impenetrable. Its shield is the blood-brain barrier, a layer of tightly connected cells that only allows an extremely selective group of molecules to pass. The barrier keeps delicate brain cells safely away from harmful substances, but it also blocks therapeutic proteins—like, for example, those that grab onto and neutralize toxic clumps in Alzheimer’s disease. One way to smuggle proteins across? A cat parasite. A  Freud’s influence waned during the 1980s and 1990s, in part because of the so-called “Freud Wars,” during which critics like

Freud’s influence waned during the 1980s and 1990s, in part because of the so-called “Freud Wars,” during which critics like

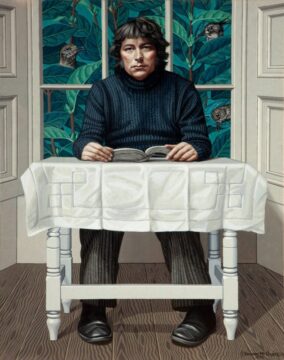

This buoyant anvil of a book has brought me to the edge of a nervous breakdown. Night after night I’m waking with Seamus Heaney sizzling through—not me, exactly, but the me I was thirty-four years ago when I first read him, in a one-windowed, mold-walled studio in Seattle, when night after night I woke with another current (is it another current?) sizzling through my circuits: ambition. Not ambition to succeed on the world’s terms (though that asserted its own maddening static) but ambition to find forms for the seethe of rage, remembrance, and wild vitality that seemed, unaccountably, like sound inside me, demanding language but prelinguistic, somehow. I felt imprisoned by these vague but stabbing haunt-songs that were, I sensed, my only means of freedom.

This buoyant anvil of a book has brought me to the edge of a nervous breakdown. Night after night I’m waking with Seamus Heaney sizzling through—not me, exactly, but the me I was thirty-four years ago when I first read him, in a one-windowed, mold-walled studio in Seattle, when night after night I woke with another current (is it another current?) sizzling through my circuits: ambition. Not ambition to succeed on the world’s terms (though that asserted its own maddening static) but ambition to find forms for the seethe of rage, remembrance, and wild vitality that seemed, unaccountably, like sound inside me, demanding language but prelinguistic, somehow. I felt imprisoned by these vague but stabbing haunt-songs that were, I sensed, my only means of freedom. One Sumerian epic poem called Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta gives the first known story about the invention of writing, by a king who has to send so many messages that his messenger can’t remember them all.

One Sumerian epic poem called Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta gives the first known story about the invention of writing, by a king who has to send so many messages that his messenger can’t remember them all. Today, researchers are looking toward building quantum computers and ways to securely transfer information using an entirely new sister field called

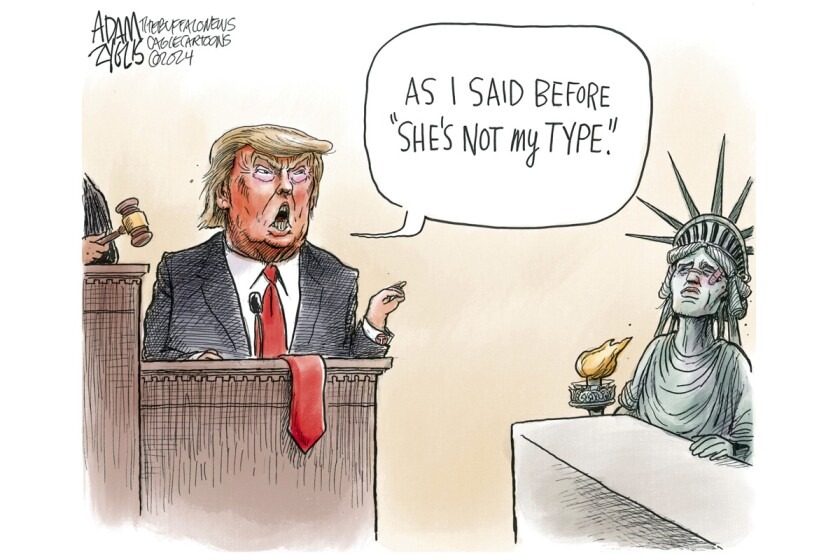

Today, researchers are looking toward building quantum computers and ways to securely transfer information using an entirely new sister field called  I first came to the United States for an academic exchange at Columbia University in 2005, and have spent the bulk of my time here since starting my PhD at Harvard University in 2007. No country changes nature overnight, and America still retains many of the virtues with which I fell in love all those years ago. But there are days when I fear that the place has been transformed so deeply that the qualities that would once have been touted as quintessentially American have forever been lost.

I first came to the United States for an academic exchange at Columbia University in 2005, and have spent the bulk of my time here since starting my PhD at Harvard University in 2007. No country changes nature overnight, and America still retains many of the virtues with which I fell in love all those years ago. But there are days when I fear that the place has been transformed so deeply that the qualities that would once have been touted as quintessentially American have forever been lost.