Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Sunday Poem

O Taste and See

The world is

not with us enough.

O taste and see

the subway Bible poster said,

meaning The Lord, meaning,

if anything, all that lives

to the imagination’s tongue,

grief, mercy, language,

tangerine, weather, to

breathe them, bite,

savor, chew, swallow, transform

into our flesh our

deaths, crossing the street, plum, quince,

living in the orchard and being

hungry, and plucking

the fruit.

by Denise Levertov

from Literature and the Writing Process

Prentice Hall, 1993

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Vic Flick (1937 – 2024) Studio Guitarist

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Peter Sinfield (1943 – 2024) Poet And Songwriter

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday, November 22, 2024

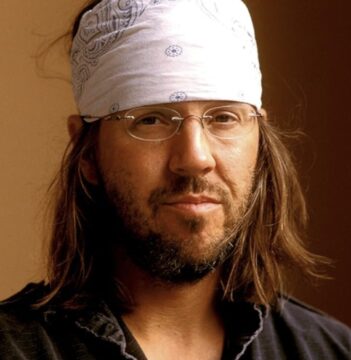

Is David Foster Wallace’s “Infinite Jest” Really, Like, Great?

John Horgan at his own website:

Like a pre-teen prodigy performing for grown-ups, Wallace is too show-offy, intent on dazzling us. Thomas Pynchon’s prose has this same adolescent “Look at me!” quality, which is why I could never get through Gravity’s Rainbow. Wallace also reminds me of J.D. Salinger, who sneerily divides characters into the cool, who get it, and the uncool, who don’t.

Like a pre-teen prodigy performing for grown-ups, Wallace is too show-offy, intent on dazzling us. Thomas Pynchon’s prose has this same adolescent “Look at me!” quality, which is why I could never get through Gravity’s Rainbow. Wallace also reminds me of J.D. Salinger, who sneerily divides characters into the cool, who get it, and the uncool, who don’t.

Wallace’s characters remain caricatures even after we get to know their most intimate, excruciating secrets. Recounting the antics of a transvestite spy or cracking-smoking hooker, Wallace smirks. He seems to see all humans, even those who suffer—and his fictional folk suffer terribly—as goofy, deserving of mockery.

Not all looooong novels by geniuses get on my nerves. I’ve not only read War & Peace and Ulysses, I’ve reread them. How do they keep me enthralled? Tolstoy’s prose, even in translation, is transparent. Joyce’s isn’t, at first, then it is. Both authors recede into the background as they magically whisk you into Russia in the early 19th century and Dublin in the early 20th. These fictional realms and their inhabitants are uncannily real, three-dimensional.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Nobel Prizes Tell a Story About Scientific Discovery

C. Brandon Ogbunu in Undark Magazine:

While Nobel Prize announcements have always been newsworthy celebrations of discovery, recent years’ events have been successful in a much more important task: fostering important global discussions around the process of science. This is especially true for the 2024 prizes, which have highlighted the increased relevance of technology and magnified existing questions about where — and how — discovery happens.

While Nobel Prize announcements have always been newsworthy celebrations of discovery, recent years’ events have been successful in a much more important task: fostering important global discussions around the process of science. This is especially true for the 2024 prizes, which have highlighted the increased relevance of technology and magnified existing questions about where — and how — discovery happens.

In the life sciences, the 2024 announcement picks up on a discourse that began after the previous year’s prize was announced. The 2023 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine was given to Drew Weissman and Katalin Karikó “for their discoveries concerning nucleoside base modifications that enabled the development of effective mRNA vaccines against COVID-19.” The award was notable because of its direct reference to Covid-19, and because of conversations surrounding Karikó’s career trajectory. After being demoted from a tenure-track position in the 1990s, Karikó has said she was forced to retire from her position at the University of Pennsylvania in 2013. The announcement created an instant stir within the scientific community around a basic question: What does the 2023 award say for how merit operates in academic science?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The ‘mad egghead’ who built a mouse utopia

Lee Alan Dugatkin in The Guardian:

Standing before the Royal Society of Medicine in London on 22 June 1972, the ecologist turned psychologist John Bumpass Calhoun, the director of the Laboratory of Brain Evolution and Behavior at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) headquartered in Bethesda, Maryland, appeared a mild-mannered, smallish man, sporting a greying goatee. After what must surely have been one of the oddest opening remarks to the Royal Society in its storied 200-plus-year history – “I shall largely speak of mice,” Calhoun began, “but my thoughts are on man, on healing, on life and its evolution” – he spoke of a long-term experiment he was running on the effects of overcrowding and population crashes in mice.

Standing before the Royal Society of Medicine in London on 22 June 1972, the ecologist turned psychologist John Bumpass Calhoun, the director of the Laboratory of Brain Evolution and Behavior at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) headquartered in Bethesda, Maryland, appeared a mild-mannered, smallish man, sporting a greying goatee. After what must surely have been one of the oddest opening remarks to the Royal Society in its storied 200-plus-year history – “I shall largely speak of mice,” Calhoun began, “but my thoughts are on man, on healing, on life and its evolution” – he spoke of a long-term experiment he was running on the effects of overcrowding and population crashes in mice.

Members of the Royal Society were scratching their heads as Calhoun told them of Universe 25, a giant experimental setup he had built and which he described as “a utopian environment constructed for mice”. Still, they listened carefully as he described that universe. They learned that to study the effects of overpopulation, Calhoun, in addition to being a scientist, needed to be a rodent city planner.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Dario Amodei on AGI: What will our future look like?

For those who didn’t have time to watch the whole four-hour video Morgan posted earlier.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Factory robot convinces 12 other robots to go on strike

Thom Dunn at Boing Boing:

Erbai, the outsider, approached the other robots by asking them, “Are you working overtime?”

Erbai, the outsider, approached the other robots by asking them, “Are you working overtime?”

To which another robot replied: “I never get off work.”

“So you’re not going home?” Erbai asked.

“I don’t have a home,” said the other robot.

“Then come home with me,” replied Erbai, before leading the bots to freedom.

And with that, the little robot had sowed the seeds for the first robot unionization effort. Or a “kidnapping,” as some news sources (read: SCABS) have characterized it.

The AI-powered Erbai ultimately convinced 12 larger robots to leave the showroom premises with it.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Michael Levin – Non-Neural Intelligence

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Cher

Elisabeth Egan at the New York Times:

Twice during a 90-minute interview about her memoir, Cher asked, “Do you think people are going to like it?”

Twice during a 90-minute interview about her memoir, Cher asked, “Do you think people are going to like it?”

Even in the annals of single-name celebrities — Sting, Madonna, Beyoncé, Zendaya — Cher is in the stratosphere of the one percent. She’s been a household name for six decades. She was 19 when she had her first No. 1 single with Sonny Bono. She won an Oscar for “Moonstruck,” an Emmy for “Cher: The Farewell Tour” and a Grammy for “Believe.” Her face has appeared on screens of all sizes, and her music has been a soundtrack for multiple generations, whether via vinyl, eight track, cassette tape, compact disc or Spotify. But wrangling a definitive account of her life struck a nerve for Cher. There were dark corners to explore and 78 years of material to sift through. And — this might have been the hardest part — she had to make peace with the fact that her most personal stories will soon be in the hands of scores of readers.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

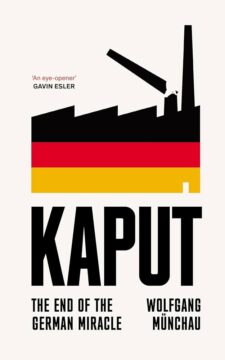

The End of the German Miracle

Howard Davies at Literary Review:

Kaput is about the problems facing Germany rather than the successes of the UK. Münchau (the clue is in the umlaut) is very pessimistic about his native land. It can do little right, in his view. In the German version of Winnie-the-Pooh, Pu der Bär, he is I-Aah, the gloomy donkey. But I-Aah often has a good point to make, and so does Münchau.

Kaput is about the problems facing Germany rather than the successes of the UK. Münchau (the clue is in the umlaut) is very pessimistic about his native land. It can do little right, in his view. In the German version of Winnie-the-Pooh, Pu der Bär, he is I-Aah, the gloomy donkey. But I-Aah often has a good point to make, and so does Münchau.

The core of his argument is that the German economic model is broken. How so? Let me count the ways. For decades it has been built on engineering excellence driving exports of manufactures, particularly cars and machine tools. Now that Germany’s Asian rivals have enhanced their productivity, that model increasingly depends on access to cheap energy. The Germans placed two large bets to sustain this model. The first involved establishing a warm and cuddly relationship with Russia, an approach pioneered by the former SPD chancellor Gerhard Schröder, whose ties with Putin were (and indeed still are) remarkably close, and sustained by Angela Merkel.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday Poem

The Shoelace

………. —excerpt

a woman, a

tire that’s flat, a

disease, a

desire: fears in front of you,

fears that hold so still

you can study them

like pieces on a

chessboard…

it’s not the large things that

send a man to the

madhouse. death he’s ready for, or

murder, incest, robbery, fire, flood…

no, it’s the continuing series of small tragedies

that send a man to the

madhouse…

not the death of his love

but a shoelace that snaps

with no time left …

The dread of life

is that swarm of trivialities

that can kill quicker than cancer

and which are always there –

license plates or taxes

or expired driver’s license,

or hiring or firing,

doing it or having it done to you, or

roaches or flies or a

broken hook on a

screen, or out of gas

or too much gas,

the sink’s stopped-up, the landlord’s drunk,

the president doesn’t care and the governor’s

crazy.

And the phone bill’s up and the market’s

down

and the light has burned out –

the hall light, the front light, the back light,

the inner light; it’s

darker than hell

and twice as

expensive.

suddenly

2 red lights in your rear-view mirror

and China and Russia and America —

with each broken shoelace

out of one hundred broken shoelaces,

one man, one woman, one

thing

enters a

madhouse.

so be careful

when you

bend over.

by Charles Bukowski

from Mockingbird Wish Me Luck

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday, November 21, 2024

The Surprising Benefits of Talking Out Loud to Yourself

Angela Haupt in Time Magazine:

Thirty years ago, when Thomas Brinthaupt became a new parent—and was in the thick of long, sleep-deprived days and nights—he started coping by talking out loud to himself. That inspired him to research why people engage in this type of self-talk. A few key reasons have emerged, including social isolation: As you might expect, people who spend lots of time alone are more likely to keep themselves company by chit-chatting out loud. (Brinthaupt’s mother lived by herself, and after he overheard her solo conversations, she told him talking to herself helped her get through the day.) The same goes for only children—who engage in self-talk more frequently than those with siblings—as well as adults who had an imaginary companion they talked to when they were kids.

Thirty years ago, when Thomas Brinthaupt became a new parent—and was in the thick of long, sleep-deprived days and nights—he started coping by talking out loud to himself. That inspired him to research why people engage in this type of self-talk. A few key reasons have emerged, including social isolation: As you might expect, people who spend lots of time alone are more likely to keep themselves company by chit-chatting out loud. (Brinthaupt’s mother lived by herself, and after he overheard her solo conversations, she told him talking to herself helped her get through the day.) The same goes for only children—who engage in self-talk more frequently than those with siblings—as well as adults who had an imaginary companion they talked to when they were kids.

The other main reason why people talk out loud to themselves is to deal with “situations that are novel or highly stressful, or where you’re not sure what to do or think or feel,” says Brinthaupt, a professor emeritus of psychology at Middle Tennessee State University. Studies have found that when you’re anxious or experiencing, for example, obsessive-compulsive tendencies, you’re much more likely to talk to yourself. Upsetting or disturbing experiences make people want to resolve or understand them—and self-talk is a tool that helps them do so, he says.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

‘A place of joy’: why scientists are joining the rush to Bluesky

Smriti Mallapaty in Nature:

Researchers are flocking to the social-media platform Bluesky, hoping to recreate the good old days of Twitter.

Researchers are flocking to the social-media platform Bluesky, hoping to recreate the good old days of Twitter.

“All the academics have suddenly migrated to Bluesky,” says Bethan Davies, a glaciologist at Newcastle University, UK. The platform has “absolutely exploded”. In the two weeks since the US presidential election, the platform has grown from close to 14 million users to nearly 21 million. Bluesky has broad appeal in large part because it looks and feels a lot like X (formerly known as Twitter), which became hugely popular with scientists, who used it to share research findings, collaborate and network. One estimate suggests that at least half a million researchers had Twitter profiles in 2022.

That was the year that billionaire Elon Musk bought the platform. He renamed it X and reduced content moderation, among other changes, prompting some researchers to leave. Since then, pornography, spam, bots and abusive content have increased on X, and community protections have decreased, say researchers. Bluesky, by contrast, offers users control over the content they see and the people they engage with, through moderation and protections such as blocking and muting features, say researchers. It is also built on an open network, which gives researchers and developers access to its data; X now charges a hefty fee for this kind of access.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How The Great Gatsby Changed the Landscape of New York City

John Marsh at Literary Hub:

Can a book change a landscape? If ever a book did, it was The Great Gatsby. And if The Great Gatsby did, it did so thanks to one of its first and most ambitious readers, the urban planner Robert Moses.

Can a book change a landscape? If ever a book did, it was The Great Gatsby. And if The Great Gatsby did, it did so thanks to one of its first and most ambitious readers, the urban planner Robert Moses.

Next year marks the one hundredth anniversary of The Great Gatsby. The novel survives in cultural memory as a narrative of star-crossed lovers (Gatsby and Daisy); as a reckoning with the elusive quality of the American dream (Gatsby and the green light); or, most commonly—witness its latest revival on Broadway—as a celebration of the excitement and excess of Jazz Age America. Few remember it for what it is: an indictment of, if not the wealthy per se, than of how wealth can deform basic human decency.

The climax of the novel makes the point. In a Manhattan hotel room, Daisy informs her husband, Tom Buchanan, that she intends to leave him and marry Gatsby. After revealing the sordid ways Gatsby has made his money—bootlegging whiskey and passing fraudulent bonds—Tom bullies Daisy into staying with him.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

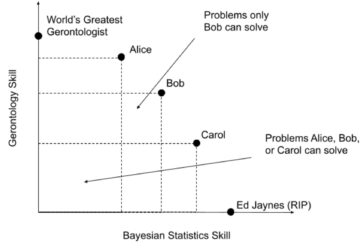

Being the (Pareto) Best in the World

John Wentworth at Less Wrong:

The generalized efficient markets (GEM) principle says, roughly, that things which would give you a big windfall of money and/or status, will not be easy. If such an opportunity were available, someone else would have already taken it. You will never find a $100 bill on the floor of Grand Central Station at rush hour, because someone would have picked it up already.

The generalized efficient markets (GEM) principle says, roughly, that things which would give you a big windfall of money and/or status, will not be easy. If such an opportunity were available, someone else would have already taken it. You will never find a $100 bill on the floor of Grand Central Station at rush hour, because someone would have picked it up already.

One way to circumvent GEM is to be the best in the world at some relevant skill. A superhuman with hawk-like eyesight and the speed of the Flash might very well be able to snag $100 bills off the floor of Grand Central. More realistically, even though financial markets are the ur-example of efficiency, a handful of firms do make impressive amounts of money by being faster than anyone else in their market. I’m unlikely to ever find a proof of the Riemann Hypothesis, but Terry Tao might. Etc.

But being the best in the world, in a sense sufficient to circumvent GEM, is not as hard as it might seem at first glance (though that doesn’t exactly make it easy). The trick is to exploit dimensionality.

Consider: becoming one of the world’s top experts in proteomics is hard. Becoming one of the world’s top experts in macroeconomic modelling is hard. But how hard is it to become sufficiently expert in proteomics and macroeconomic modelling that nobody is better than you at both simultaneously? In other words, how hard is it to reach the Pareto frontier?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

David Brooks: How Ivy League Admissions Broke America

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How Scientific American’s Departing Editor Helped Degrade Science

Jesse Singal at Reason:

When Scientific American was bad under Helmuth, it was really bad. For example, did you know that “Denial of Evolution Is a Form of White Supremacy“? Or that the normal distribution—a vital and basic statistical concept—is inherently suspect? No, really: Three days after the legendary biologist and author E.O. Wilson died, SciAm published a surreal hit piece about him in which the author lamented “his dangerous ideas on what factors influence human behavior.” That author also explained that “the so-called normal distribution of statistics assumes that there are default humans who serve as the standard that the rest of us can be accurately measured against.” But the normal distribution doesn’t make any such value judgments, and only someone lacking in basic education about stats—someone who definitely shouldn’t be writing about the subject for a top magazine—could make such a claim.

When Scientific American was bad under Helmuth, it was really bad. For example, did you know that “Denial of Evolution Is a Form of White Supremacy“? Or that the normal distribution—a vital and basic statistical concept—is inherently suspect? No, really: Three days after the legendary biologist and author E.O. Wilson died, SciAm published a surreal hit piece about him in which the author lamented “his dangerous ideas on what factors influence human behavior.” That author also explained that “the so-called normal distribution of statistics assumes that there are default humans who serve as the standard that the rest of us can be accurately measured against.” But the normal distribution doesn’t make any such value judgments, and only someone lacking in basic education about stats—someone who definitely shouldn’t be writing about the subject for a top magazine—could make such a claim.

Some of the magazine’s Helmuth-era output made the posthumous drive-by against Wilson look Pulitzer-worthy by comparison.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Historical and Philosophical Origins of Goth and Gothic Horror

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.