Colin Jones at Literary Review:

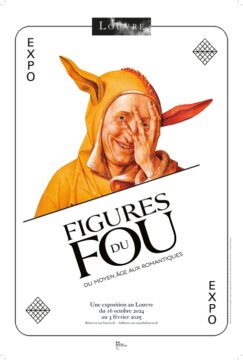

We tend to view the figure of the medieval and Renaissance fool or jester through 19th-century filters – to think of Victor Hugo’s Quasimodo and Verdi’s Rigoletto. Perhaps the show’s most striking achievement is to transcend these anachronistic and wistful habits and to reveal how much more complicated – and fascinating – the world of the fool has been.

We tend to view the figure of the medieval and Renaissance fool or jester through 19th-century filters – to think of Victor Hugo’s Quasimodo and Verdi’s Rigoletto. Perhaps the show’s most striking achievement is to transcend these anachronistic and wistful habits and to reveal how much more complicated – and fascinating – the world of the fool has been.

The exhibition’s organisers, Elisabeth Antoine-König and Pierre-Yves Le Pogam, have chosen not to approach the subject through the anachronistic prism of mental illness. As they observe, the category of ‘natural fool’ in earlier times was often held to include the mentally or physically impaired (it could encompass cultural outsiders as well). They place the exhibition’s emphasis on ‘artificial fools’ – those who assumed a fool’s identity. Playing the fool might be done with passionate sincerity – by the likes of St Francis of Assisi, self-declaredly ‘God’s fool’ – or with sardonic insouciance and comic and sometimes malevolent intent.

Court jesters, masters of the art of playing the fool, are at the heart of the show.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The English historian J.A. Froude was famously gloomy about the ultimate prospects for his chosen branch of literature. “To be entirely just in our estimate of other ages is not difficult,” he said. “It is impossible.” Froude’s words came to mind the other day when I encountered Tucker Carlson’s interview with the podcaster Darryl Cooper, whose opinions about World War II may politely be described as “controversial.”

The English historian J.A. Froude was famously gloomy about the ultimate prospects for his chosen branch of literature. “To be entirely just in our estimate of other ages is not difficult,” he said. “It is impossible.” Froude’s words came to mind the other day when I encountered Tucker Carlson’s interview with the podcaster Darryl Cooper, whose opinions about World War II may politely be described as “controversial.” T

T I now present to you the Ultimate List, otherwise known as the List of Lists—in which I read all the Best Of lists and count which books are recommended most.

I now present to you the Ultimate List, otherwise known as the List of Lists—in which I read all the Best Of lists and count which books are recommended most. On December 20, OpenAI’s o3 system scored 85% on the

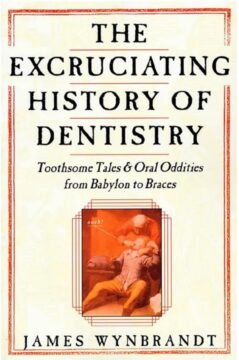

On December 20, OpenAI’s o3 system scored 85% on the  The writer P. J. O’Rourke famously quipped, “When you think of the good old days, think one word: dentistry.” So let us take his advice. James Wynbrandt’s The Excruciating History of Dentistry: Toothsome Tales & Oral Oddities from Babylon to Braces provides plenty to chew on. As the New York Times Book Review put it, “Wynbrandt has clearly done his homework.”

The writer P. J. O’Rourke famously quipped, “When you think of the good old days, think one word: dentistry.” So let us take his advice. James Wynbrandt’s The Excruciating History of Dentistry: Toothsome Tales & Oral Oddities from Babylon to Braces provides plenty to chew on. As the New York Times Book Review put it, “Wynbrandt has clearly done his homework.” Sharks present an interesting case study because unlike other fast swimmers such as tuna or swordfish, which have smooth skin surfaces, shark skin is rough—covered in teeth-like structures called denticles. Although ichthyologists have known for decades that denticles likely hold the key to a shark’s ability to quickly and efficiently move through the water, how they contribute to speed remained a mystery.

Sharks present an interesting case study because unlike other fast swimmers such as tuna or swordfish, which have smooth skin surfaces, shark skin is rough—covered in teeth-like structures called denticles. Although ichthyologists have known for decades that denticles likely hold the key to a shark’s ability to quickly and efficiently move through the water, how they contribute to speed remained a mystery. I

I When exactly did we stop

When exactly did we stop

In 2017, the MIT Media Lab launched MyGoodness, an online game billed as a way to teach players to “maximize the impact of [their] charitable donations.”

In 2017, the MIT Media Lab launched MyGoodness, an online game billed as a way to teach players to “maximize the impact of [their] charitable donations.” Evolution was a “training process” selecting for reproductive success. But humans’ goals don’t entirely center around reproducing. We sort of want reproduction itself (many people want to have children on a deep level). But we also correlates of reproduction, both direct (eg having sex), indirect (dating, getting married), and counterproductive (porn, masturbation). Other drives are even less direct, aimed at targets that aren’t related to reproduction at all but which in practice caused us to reproduce more (hunger, self-preservation, social status, career success). On the fringe, we have fake correlates of the indirect correlates – some people spend their whole lives trying to build a really good coin collection; others get addicted to heroin.

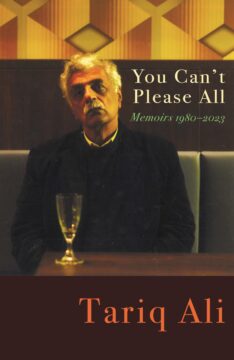

Evolution was a “training process” selecting for reproductive success. But humans’ goals don’t entirely center around reproducing. We sort of want reproduction itself (many people want to have children on a deep level). But we also correlates of reproduction, both direct (eg having sex), indirect (dating, getting married), and counterproductive (porn, masturbation). Other drives are even less direct, aimed at targets that aren’t related to reproduction at all but which in practice caused us to reproduce more (hunger, self-preservation, social status, career success). On the fringe, we have fake correlates of the indirect correlates – some people spend their whole lives trying to build a really good coin collection; others get addicted to heroin. One afternoon in the early 1980s, Tariq Ali, wearing only a towel, leapt into a room in Private Eye’s Soho offices. His mission was to liberate the magazine’s editor, Richard Ingrams, from a tiresome interview with Daily Mail hack Lynda-Lee Potter. “Mr Ingrosse, sir,” said Ali, posing as an Indian guru, “Time for meditation. Please remove all clothes.”

One afternoon in the early 1980s, Tariq Ali, wearing only a towel, leapt into a room in Private Eye’s Soho offices. His mission was to liberate the magazine’s editor, Richard Ingrams, from a tiresome interview with Daily Mail hack Lynda-Lee Potter. “Mr Ingrosse, sir,” said Ali, posing as an Indian guru, “Time for meditation. Please remove all clothes.” In a 1939 essay, the critic Philip Rahv

In a 1939 essay, the critic Philip Rahv