Richard Skinner in 3:AM Magazine:

If you tell the story of Citizen Kane, it’s not much of a story. An old rich mogul man is dead. He said a word we don’t understand. We don’t discover so much, just some pieces of his life and finally it is just a sled. Is that a story? It is not much. What makes Citizen Kane so interesting is the way [Welles] told us about the man—intriguing us about what people think about him.

— Agnès Varda

If Agnès Varda’s 1985 movie Vagabond is like any other movie, then it would be Citizen Kane. When you’ve seen both, you see that Varda almost certainly used the structure of Orson Welles’ 1941 movie as a blueprint for her own. Both start with a death, both are an investigation into a life, both end inconclusively.

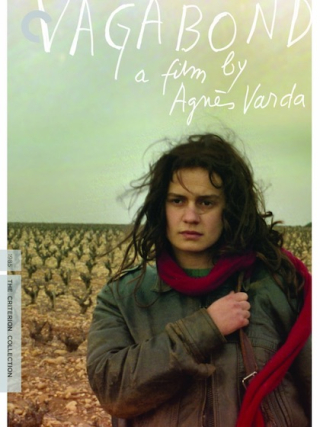

Vagabond is about a young woman, Mona, played by Sandrine Bonnaire, who has perished from the cold, and the attempts by numerous people who crossed her path to assign meaning to her chosen way of living. There are 18 ‘visions’ of Mona presented by those who came across her. The film is a series of gazes, of one-way exchanges from different people—dropouts, hippies, a prostitute, an itinerant worker, a maid (the ‘punctum’ moment when the maid addresses the camera directly)—but each of these ‘witnesses’ is not seeing Mona, but a reflection of their own regrets, secrets, longings. As the film makes transparently clear, Mona refuses to be co-opted into any image they may have of her. She defies identification and empties the mirror of any meaning. Her peripatetic and solitary existence (‘I move’) is a deliberate choice and functions metonymically for her unfixability. Mona is the blank centre of the film and she leaves no trace of her existence.

In Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962), Agnès Varda made frequent use of tracking shots to follow Cléo along Parisian streets; there is a lot of the same kind of camerawork in Vagabond. But while the narcissistic Cléo is nearly always in the center of the frame, Mona can barely stay in the picture. As she walks along beaches, streets, fields—confirming the viewer’s sense of her restlessness and rootlessness—she either walks into the frame of an already-in-motion tracking shot, or falls behind, or walks out of frame as the camera keeps moving. It’s as though she is on the periphery of her own movie. Varda says, “The whole film is one long tracking shot … we cut it up into separate pieces and in between them are the ‘adventures’.” There are 14 of these highly formal tracking shots and they all frame Mona at some kind of juncture. They are Mona’s ‘signature’.

More here.