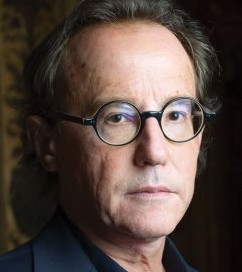

David Skinner in Humanities:

To change the world is the dream of many an ambitious figure, but what about those who want to unchange it? Who dream of the old order that existed before the 1960s, or before World War I, or before the French Revolution?

To change the world is the dream of many an ambitious figure, but what about those who want to unchange it? Who dream of the old order that existed before the 1960s, or before World War I, or before the French Revolution?

Mark Lilla is a professor of humanities at Columbia University and a contributor to the New York Review of Books. In his new collection of essays, The Shipwrecked Mind: On Political Reaction, he explores the lives and ideas of sundry reactionaries for whom the last revolution “marked the end of a glorious journey, not the beginning of one.” His gallery of backward-looking thinkers stretches from the German-Jewish thinker Franz Rosenzweig to the émigré philosophers Leo Strauss and Eric Voegelin, and all the way to the political Islamists who dream of restoring a caliphate.

In 1992, Lilla received a grant from NEH to support translations of postwar political theory in France for a book he edited called New French Thought. His interest in continental philosophy and the modern era has also resulted in books on Giambattista Vico and the place of the religious imagination in contemporary politics. This fall New York Review Books reissued a prequel to the current volume called The Reckless Mind: Intellectuals in Politics, which is about the dangerous relationship between politics and philosophy as evidenced in the lives of Martin Heidegger, Carl Schmitt, and others.

Recently, HUMANITIES emailed Lilla several questions and he emailed us back several answers.

HUMANITIES: What is the shipwrecked mind? Why is it shipwrecked?

MARK LILLA: One of the most common metaphors for history, and for time itself, is that of a river. Time flows, history has currents, etc. While thinking about this image, it occurred to me that some people believe that time carries us along and all we can do is passively experience the ride. Think of cyclical theories of history or even cosmology: The world runs its course, is destroyed, and is then reborn to travel the cycle again.

Other people, though, have a catastrophic conception of history: The river flows but it may not be heading in the right direction. It might flow into a channel full of shoals or rocks, where a ship can run aground or be shattered. This, I think, is the picture of history that reactionaries have.

More here.