Yung In Chae in Avidly:

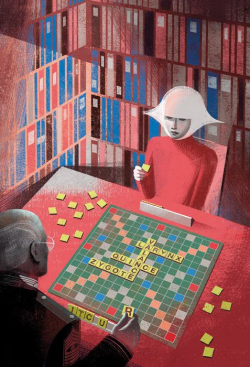

You may remember the “Romans Go Home” scene from Monty Python’s Life of Brian. In the dead of the night, a centurion catches Brian painting the (grammatically incorrect) Latin slogan Romanes eunt domus on the walls of Pontius Pilate’s house. Revolutionary graffiti should spell the end of Brian—except, it doesn’t, because the centurion is angry about neither the medium nor the message but the grammar, and he makes Brian write the correct version, Romani ite domum, one hundred times as punishment. By sunrise, anti-Roman propaganda covers the palace. In 2017, The Handmaid’s Tale painted another Latin phrase, nolite te bastardes carborundorum, on the walls of the Internet, and once again the centurion became the butt of the joke by not getting it. “Aha,” at least one “think piece”/centurion said, “the famous phrase from Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale is grammatically incorrect!” He then explained that while nolite and te are okay, bastardes is a bastardized (ha) word, and carborundorum comes from an older, gerundive-like name for silicon carbide (carborundum). This, he concluded, reveals a greater truth about the book and Hulu show, one so obvious that he doesn’t question what it is. You don’t have to be a classicist, or know Latin, in order to figure out that nolite te bastardes carborundorum is fake. You can just read The Handmaid’s Tale, which makes no pretension to its authenticity. Roughly two hundred pages in, the Commander informs Offred, who has discovered the phrase carved into her cupboard, “That’s not real Latin […] That’s just a joke.” Atwood herself told Elisabeth Moss the same thing in Time.

You may remember the “Romans Go Home” scene from Monty Python’s Life of Brian. In the dead of the night, a centurion catches Brian painting the (grammatically incorrect) Latin slogan Romanes eunt domus on the walls of Pontius Pilate’s house. Revolutionary graffiti should spell the end of Brian—except, it doesn’t, because the centurion is angry about neither the medium nor the message but the grammar, and he makes Brian write the correct version, Romani ite domum, one hundred times as punishment. By sunrise, anti-Roman propaganda covers the palace. In 2017, The Handmaid’s Tale painted another Latin phrase, nolite te bastardes carborundorum, on the walls of the Internet, and once again the centurion became the butt of the joke by not getting it. “Aha,” at least one “think piece”/centurion said, “the famous phrase from Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale is grammatically incorrect!” He then explained that while nolite and te are okay, bastardes is a bastardized (ha) word, and carborundorum comes from an older, gerundive-like name for silicon carbide (carborundum). This, he concluded, reveals a greater truth about the book and Hulu show, one so obvious that he doesn’t question what it is. You don’t have to be a classicist, or know Latin, in order to figure out that nolite te bastardes carborundorum is fake. You can just read The Handmaid’s Tale, which makes no pretension to its authenticity. Roughly two hundred pages in, the Commander informs Offred, who has discovered the phrase carved into her cupboard, “That’s not real Latin […] That’s just a joke.” Atwood herself told Elisabeth Moss the same thing in Time.

As for why it’s fake, history supplies the facts, or more accurately, fun facts. Does The Handmaid’s Tale reveal anything this time? “It’s sort of hard to explain why it’s funny unless you know Latin,” the centurion—I mean, Commander—says. Oh. Maybe he wanted to add, fun fact never means fun for everyone. After all, the Commander’s revelation horrifies Offred: “It can’t only be a joke. Have I risked this, made a grab at knowledge, for a mere joke?” She had been reciting nolite te bastardes caborundorum as a prayer, hoping for meaning. In the end, how real or fake the Latin is doesn’t matter for the meaning. Upon hearing the translation—“don’t let the bastards grind you down”—Offred understands why her Handmaid predecessor wrote the phrase, and realizes that the Commander had secretly met with her, too, because where else would she have learned it? The person who fails to understand or realize anything is, for all his Latin, the Commander.

More here.