Emily LaBarge at Bookforum:

For some readers, Howe’s work seems inscrutable or obtuse—obscure for the sake of difficulty as a kind of meaning in itself. Indeed, the poems stand awkwardly as individual works, and are best read as a volume. Taken as such, they offer a rewarding route to how one might construct a life—and a life’s work—from diving into language, the past, archival sources, and visual art. There is freedom in vastness and there is always more—more ideas, more ways of speaking and hearing, listening and knowing—to be found. Howe convinces us that intuited connections are real and possess a logic of their own, and that supposed breaks in continuity, in history or associations or sentences, are often the very place we should look to forge new connections. To stutter, to recombine or pull apart phonemes and line breaks, to wrench metaphors and to wrongly employ words, to cut and paste texts in images, shapes, lines, is to uncover so much possibility. Most critically, it is to admit and to relish the fact that we do not know all the ways in which we do not know—to be open to the grace of “not being in the no.”

For some readers, Howe’s work seems inscrutable or obtuse—obscure for the sake of difficulty as a kind of meaning in itself. Indeed, the poems stand awkwardly as individual works, and are best read as a volume. Taken as such, they offer a rewarding route to how one might construct a life—and a life’s work—from diving into language, the past, archival sources, and visual art. There is freedom in vastness and there is always more—more ideas, more ways of speaking and hearing, listening and knowing—to be found. Howe convinces us that intuited connections are real and possess a logic of their own, and that supposed breaks in continuity, in history or associations or sentences, are often the very place we should look to forge new connections. To stutter, to recombine or pull apart phonemes and line breaks, to wrench metaphors and to wrongly employ words, to cut and paste texts in images, shapes, lines, is to uncover so much possibility. Most critically, it is to admit and to relish the fact that we do not know all the ways in which we do not know—to be open to the grace of “not being in the no.”

more here.

“I am glad you’ve read the Heart of D. tho’ of course it’s an awful fudge,” Joseph Conrad wrote to Roger Casement in late 1903. Casement, an Irish diplomat working for the British Foreign Office, had just returned to London from Belgium’s African colony, the Congo Free State, and was about to submit a report to Parliament detailing the existence of a vast system of slavery used to extract ivory and rubber. Looking to draw public attention to the atrocities, Casement traveled to the author’s home outside London to attempt to recruit him into the Congo Reform Association. Conrad was sympathetic: Africa, he told Casement, shared with Europe “the consciousness of the universe in which we live,” and it had been difficult for him to learn that the horrors he witnessed on his 1890 trip up the Congo River had only gotten worse. But he resisted playing the part of an on-the-spot authority and begged off joining Casement’s association. “I would help him but it is not in me,” Conrad later explained to a friend. “I am only a wretched novelist inventing wretched stories and not even up to that miserable game.”

“I am glad you’ve read the Heart of D. tho’ of course it’s an awful fudge,” Joseph Conrad wrote to Roger Casement in late 1903. Casement, an Irish diplomat working for the British Foreign Office, had just returned to London from Belgium’s African colony, the Congo Free State, and was about to submit a report to Parliament detailing the existence of a vast system of slavery used to extract ivory and rubber. Looking to draw public attention to the atrocities, Casement traveled to the author’s home outside London to attempt to recruit him into the Congo Reform Association. Conrad was sympathetic: Africa, he told Casement, shared with Europe “the consciousness of the universe in which we live,” and it had been difficult for him to learn that the horrors he witnessed on his 1890 trip up the Congo River had only gotten worse. But he resisted playing the part of an on-the-spot authority and begged off joining Casement’s association. “I would help him but it is not in me,” Conrad later explained to a friend. “I am only a wretched novelist inventing wretched stories and not even up to that miserable game.” The scientific

The scientific I would like to write about the bullshitization of academic life: that is, the degree to which those involved in teaching and academic management spend more and more of their time involved in tasks which they secretly — or not so secretly — believe to be entirely pointless.

I would like to write about the bullshitization of academic life: that is, the degree to which those involved in teaching and academic management spend more and more of their time involved in tasks which they secretly — or not so secretly — believe to be entirely pointless.

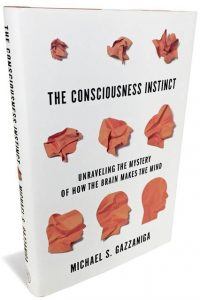

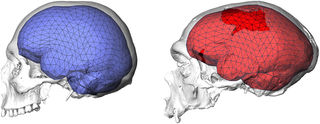

Three decades after being awarded the Nobel Prize for his discovery of DNA, Francis Crick wrote a book about consciousness, “The Astonishing Hypothesis: The Scientific Search for the Soul.” It was momentous: A world-renowned scientist had decided to directly confront the mind/body problem, the centuries-old challenge of reconciling the brain, a gelatinous mass of physical tissue, and human consciousness, the realm of emotion, volition and boundless imagination. Crick’s contention that the human mind arises from neurons in the brain rather than from an ineffable soul is perhaps less astonishing today, when this premise is nearly universally accepted among neuroscientists. But it still hints at something remarkable about Crick’s own mind. Why would a Nobel-winning scientist, already credited with discovering the secret of life, decide to switch gears and focus on an inquiry not only in a different field but so scientifically impenetrable as to have earned nicknames like “the hard problem” and “the last great mystery of science?” Crick answered this question with “what I called the gossip test: What you’re really interested in is what you gossip about. Gossip is things you’re interested in, but you don’t know much about.” In short: genuine curiosity.

Three decades after being awarded the Nobel Prize for his discovery of DNA, Francis Crick wrote a book about consciousness, “The Astonishing Hypothesis: The Scientific Search for the Soul.” It was momentous: A world-renowned scientist had decided to directly confront the mind/body problem, the centuries-old challenge of reconciling the brain, a gelatinous mass of physical tissue, and human consciousness, the realm of emotion, volition and boundless imagination. Crick’s contention that the human mind arises from neurons in the brain rather than from an ineffable soul is perhaps less astonishing today, when this premise is nearly universally accepted among neuroscientists. But it still hints at something remarkable about Crick’s own mind. Why would a Nobel-winning scientist, already credited with discovering the secret of life, decide to switch gears and focus on an inquiry not only in a different field but so scientifically impenetrable as to have earned nicknames like “the hard problem” and “the last great mystery of science?” Crick answered this question with “what I called the gossip test: What you’re really interested in is what you gossip about. Gossip is things you’re interested in, but you don’t know much about.” In short: genuine curiosity.

The idea that Debussy is one of music’s great revolutionaries still causes consternation. Many who consider themselves fans are aware only of the sensual timbres and mellifluous images in sound, often inspired by literary or visual allusion: water, air, wind, moonlight, at once static and mobile. How can music so apparently formless and exquisite also trigger innovation?

The idea that Debussy is one of music’s great revolutionaries still causes consternation. Many who consider themselves fans are aware only of the sensual timbres and mellifluous images in sound, often inspired by literary or visual allusion: water, air, wind, moonlight, at once static and mobile. How can music so apparently formless and exquisite also trigger innovation? Late last year, I witnessed an extraordinary surgical procedure at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio. The patient was a middle-aged man who was born with a leaky valve at the root of his aorta, the wide-bored blood vessel that arcs out of the human heart and carries blood to the upper and lower reaches of the body. That faulty valve had been replaced several years ago but wasn’t working properly and was leaking again. To fix the valve, the cardiac surgeon intended to remove the old tissue, resecting the ring-shaped wall of the aorta around it. He would then build a new vessel wall, crafted from the heart-lining of a cow, and stitch a new valve into that freshly built ring of aorta. It was the most exquisite form of human tailoring that I had ever seen. The surgical suite ran with unobstructed, preternatural smoothness. Minutes before the incision was made, the charge nurse called a “time out.” The patient’s identity was confirmed by the name tag on his wrist. The surgeon reviewed the anatomy, while the nurses — six in all — took their positions around the bed and identified themselves by name. A large steel tray, with needles, sponges, gauze and scalpels, was placed in front of the head nurse. Each time a scalpel or sponge was removed from the tray, as I recall, the nurse checked off a box on a list; when it was returned, the box was checked off again. The old tray was not exchanged for a new one, I noted, until every item had been ticked off twice. It was a simple, effective method to stave off a devastating but avoidable human error: leaving a needle or sponge inside a patient’s body.

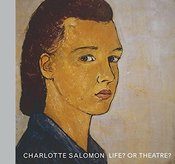

Late last year, I witnessed an extraordinary surgical procedure at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio. The patient was a middle-aged man who was born with a leaky valve at the root of his aorta, the wide-bored blood vessel that arcs out of the human heart and carries blood to the upper and lower reaches of the body. That faulty valve had been replaced several years ago but wasn’t working properly and was leaking again. To fix the valve, the cardiac surgeon intended to remove the old tissue, resecting the ring-shaped wall of the aorta around it. He would then build a new vessel wall, crafted from the heart-lining of a cow, and stitch a new valve into that freshly built ring of aorta. It was the most exquisite form of human tailoring that I had ever seen. The surgical suite ran with unobstructed, preternatural smoothness. Minutes before the incision was made, the charge nurse called a “time out.” The patient’s identity was confirmed by the name tag on his wrist. The surgeon reviewed the anatomy, while the nurses — six in all — took their positions around the bed and identified themselves by name. A large steel tray, with needles, sponges, gauze and scalpels, was placed in front of the head nurse. Each time a scalpel or sponge was removed from the tray, as I recall, the nurse checked off a box on a list; when it was returned, the box was checked off again. The old tray was not exchanged for a new one, I noted, until every item had been ticked off twice. It was a simple, effective method to stave off a devastating but avoidable human error: leaving a needle or sponge inside a patient’s body. Origin stories are woven with many threads: Some we spin ourselves, while others we inherit. The great German artist Charlotte Salomon (1917–1943) accounted for herself—for who she was, and why she was, and where she came from—not by wondering what of herself was fact and what was fiction. Rather, the real and present question was Leben? oder Theater? (Life? or Theatre?). In other words, how to distinguish genuine presence and raw experience from the spectacle and folly of human making.

Origin stories are woven with many threads: Some we spin ourselves, while others we inherit. The great German artist Charlotte Salomon (1917–1943) accounted for herself—for who she was, and why she was, and where she came from—not by wondering what of herself was fact and what was fiction. Rather, the real and present question was Leben? oder Theater? (Life? or Theatre?). In other words, how to distinguish genuine presence and raw experience from the spectacle and folly of human making. There’s

There’s In recent months, there’s been a groundswell of evidence showing that more volume in both the left and right hemispheres of the cerebellum (Latin for “little

In recent months, there’s been a groundswell of evidence showing that more volume in both the left and right hemispheres of the cerebellum (Latin for “little  One hundred and sixty years ago, at a time when the light bulb was not yet invented, Karl Marx predicted that robots would replace humans in the workplace.

One hundred and sixty years ago, at a time when the light bulb was not yet invented, Karl Marx predicted that robots would replace humans in the workplace. Politics on both sides of the Atlantic is being played out in the costumes of dead generations. Trump won the White House with a Reagan campaign slogan, pledging to bring back factory jobs and tariff wars. Democrats believe desperately in the existence of Russian conspiracies. British conservatives yearn for the nineteenth century, while academics at Oxford seek an “intelligent Christian ethic of empire.” Jeremy Corbyn has made postwar socialism popular again, with the help of a line from Shelley. Such retromania might not be so surprising—every age of crisis, as Marx famously argued, conjures up the spirits of the past for guidance and inspiration. But it is harder to account for a ghostly presence that provides neither: the public intellectual who wants to fight about the Enlightenment.

Politics on both sides of the Atlantic is being played out in the costumes of dead generations. Trump won the White House with a Reagan campaign slogan, pledging to bring back factory jobs and tariff wars. Democrats believe desperately in the existence of Russian conspiracies. British conservatives yearn for the nineteenth century, while academics at Oxford seek an “intelligent Christian ethic of empire.” Jeremy Corbyn has made postwar socialism popular again, with the help of a line from Shelley. Such retromania might not be so surprising—every age of crisis, as Marx famously argued, conjures up the spirits of the past for guidance and inspiration. But it is harder to account for a ghostly presence that provides neither: the public intellectual who wants to fight about the Enlightenment.

O

O