Matthew Warren in Nature:

6.6 million — that’s how many spots on the human genome Sekar Kathiresan looks at to calculate a person’s risk of developing coronary artery disease. Kathiresan has found that combinations of single DNA-letter differences from person to person in these select locations could help to predict whether someone will succumb to one of the leading causes of death worldwide. It’s anyone’s guess what the majority of those As, Cs, Ts and Gs are doing. Nevertheless, Kathiresan says, “you can stratify people into clear trajectories for heart attack, based on something you have fixed from birth”. Kathiresan, a geneticist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, isn’t alone in counting outrageously high numbers of variants. The polygenic risk scores he has developed are part of a cutting-edge approach in the hunt for the genetic contributors to common diseases. Over the past two decades, researchers have struggled to account for the heritability of conditions including heart disease, diabetes and schizophrenia. Polygenic scores add together the small — sometimes infinitesimal — contributions of tens to millions of spots on the genome, to create some of the most powerful genetic diagnostics to date. This approach has taken off thanks to a number of well-resourced cohort studies and large data repositories, such as the UK Biobank (see pages 194, 203 and 210), which collect vast quantities of health information alongside DNA data from hundreds of thousands of people. And some studies published in the past year or so have been able to analyse more than a million participants by combining information from such sources, increasing scientists’ ability to detect tiny effects.

6.6 million — that’s how many spots on the human genome Sekar Kathiresan looks at to calculate a person’s risk of developing coronary artery disease. Kathiresan has found that combinations of single DNA-letter differences from person to person in these select locations could help to predict whether someone will succumb to one of the leading causes of death worldwide. It’s anyone’s guess what the majority of those As, Cs, Ts and Gs are doing. Nevertheless, Kathiresan says, “you can stratify people into clear trajectories for heart attack, based on something you have fixed from birth”. Kathiresan, a geneticist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, isn’t alone in counting outrageously high numbers of variants. The polygenic risk scores he has developed are part of a cutting-edge approach in the hunt for the genetic contributors to common diseases. Over the past two decades, researchers have struggled to account for the heritability of conditions including heart disease, diabetes and schizophrenia. Polygenic scores add together the small — sometimes infinitesimal — contributions of tens to millions of spots on the genome, to create some of the most powerful genetic diagnostics to date. This approach has taken off thanks to a number of well-resourced cohort studies and large data repositories, such as the UK Biobank (see pages 194, 203 and 210), which collect vast quantities of health information alongside DNA data from hundreds of thousands of people. And some studies published in the past year or so have been able to analyse more than a million participants by combining information from such sources, increasing scientists’ ability to detect tiny effects.

Supporters say that polygenic scores could be the next great stride in genomic medicine, but the approach has generated considerable debate. Some research presents ethical quandaries as to how the scores might be used: for example, in predicting academic performance. Critics also worry about how people will interpret the complex and sometimes equivocal information that emerges from the tests. And because leading biobanks lack ethnic and geographic diversity, the current crop of genetic screening tools might have predictive power only for the populations represented in the databases.

More here.

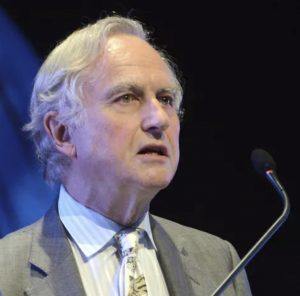

Many atheists think that their atheism is the product of rational thinking. They use arguments such as “I don’t believe in God, I believe in science” to explain that evidence and logic, rather than supernatural belief and dogma, underpin their thinking. But just because you believe in evidence-based, scientific research – which is subject to strict checks and procedures – doesn’t mean that your mind works in the same way.

Many atheists think that their atheism is the product of rational thinking. They use arguments such as “I don’t believe in God, I believe in science” to explain that evidence and logic, rather than supernatural belief and dogma, underpin their thinking. But just because you believe in evidence-based, scientific research – which is subject to strict checks and procedures – doesn’t mean that your mind works in the same way. Imagine throwing a baseball and not being able to tell exactly where it’ll go, despite your ability to throw accurately. Say that you are able to predict only that it will end up, with equal probability, in the mitt of one of five catchers. The baseball randomly materialises in one catcher’s mitt, while the others come up empty. And before it’s caught, you cannot talk of the baseball being real – for it has no deterministic trajectory from thrower to catcher. Until it becomes ‘real’, the ball can potentially appear in any one of the five mitts. This might seem bizarre, but the subatomic world studied by quantum physicists behaves in this counterintuitive way.

Imagine throwing a baseball and not being able to tell exactly where it’ll go, despite your ability to throw accurately. Say that you are able to predict only that it will end up, with equal probability, in the mitt of one of five catchers. The baseball randomly materialises in one catcher’s mitt, while the others come up empty. And before it’s caught, you cannot talk of the baseball being real – for it has no deterministic trajectory from thrower to catcher. Until it becomes ‘real’, the ball can potentially appear in any one of the five mitts. This might seem bizarre, but the subatomic world studied by quantum physicists behaves in this counterintuitive way. Good news and bad news arrived this week

Good news and bad news arrived this week  At the risk of not sounding patriotic, as I grew older, I came into some conflict with the aesthetic of Trinidadian jazz.

At the risk of not sounding patriotic, as I grew older, I came into some conflict with the aesthetic of Trinidadian jazz. Prepare to grapple with the cosmic grandiosity and optical hot-messes of that 19th-century French freak of painterly nature, Eugène Delacroix, who’s churning, turgid, crimson-tinged floridity has enkindled the respiratory systems of artists since he first debuted at the Paris Salon of 1822 — and given many others agita.

Prepare to grapple with the cosmic grandiosity and optical hot-messes of that 19th-century French freak of painterly nature, Eugène Delacroix, who’s churning, turgid, crimson-tinged floridity has enkindled the respiratory systems of artists since he first debuted at the Paris Salon of 1822 — and given many others agita. In several respects, John Wray’s “

In several respects, John Wray’s “ Almost all Marxists have imagined themselves to be part of a global community. More than perhaps any other modern ideology, Marxism has given its adherents a sense of being connected across regions, countries and continents. The activists, thinkers, politicians, students, workers, guerrilla fighters and party apparatchiks who, throughout the 20th century, claimed Marxist ideals for themselves rarely agreed on what Marxism was or where it was headed. But they knew that they were not alone. At its height, Marxism created a web of interconnected communities at least as powerful as the Muslim ummah, complete with its own heretics, infidels, rogue saviours and clerics.

Almost all Marxists have imagined themselves to be part of a global community. More than perhaps any other modern ideology, Marxism has given its adherents a sense of being connected across regions, countries and continents. The activists, thinkers, politicians, students, workers, guerrilla fighters and party apparatchiks who, throughout the 20th century, claimed Marxist ideals for themselves rarely agreed on what Marxism was or where it was headed. But they knew that they were not alone. At its height, Marxism created a web of interconnected communities at least as powerful as the Muslim ummah, complete with its own heretics, infidels, rogue saviours and clerics. During his elder years, my great-grandfather, the post-Impressionist artist Sam Rothbort, tried to paint back into existence the murdered world of his shtetl childhood. Amid the hundreds of watercolors that he called Memory Paintings, one stood out. A girl silhouetted against some cottages, her dress the same color as the crepuscular sky above. A moment before, she’d hurled a rock through one now-shattered cottage window. On the painting’s margin, her boyfriend offers more rocks.

During his elder years, my great-grandfather, the post-Impressionist artist Sam Rothbort, tried to paint back into existence the murdered world of his shtetl childhood. Amid the hundreds of watercolors that he called Memory Paintings, one stood out. A girl silhouetted against some cottages, her dress the same color as the crepuscular sky above. A moment before, she’d hurled a rock through one now-shattered cottage window. On the painting’s margin, her boyfriend offers more rocks. For the first time in 55 years, a woman has won the Nobel Prize in physics —Prof. Donna Strickland. This win has publicly highlighted that

For the first time in 55 years, a woman has won the Nobel Prize in physics —Prof. Donna Strickland. This win has publicly highlighted that  You brought up this other question of why is it so important for people to leave, and the thing I want to say is that, because of addiction and because of network effects, I realize that only a small minority of people can do it, and I don’t know how many I have influenced to get off of there. I don’t have a means of measuring that. But here’s what I would say: there have been times before, recently and even in America, when society had to confront mass addiction that had a commercial component.

You brought up this other question of why is it so important for people to leave, and the thing I want to say is that, because of addiction and because of network effects, I realize that only a small minority of people can do it, and I don’t know how many I have influenced to get off of there. I don’t have a means of measuring that. But here’s what I would say: there have been times before, recently and even in America, when society had to confront mass addiction that had a commercial component. We really are sleeping less. As Crary writes, in the early twentieth century, adults slept an unthinkable ten hours every night on average. A generation ago, people were tucking in for eight hours. Today, the average North American adult sleeps a paltry six-and-a-half hours every night. This is often blamed on our devices, which do play a major role. But Crary argues that, interrelatedly, the forces of twenty-first-century capitalism have shown an obsessive enthusiasm for destroying sleep.

We really are sleeping less. As Crary writes, in the early twentieth century, adults slept an unthinkable ten hours every night on average. A generation ago, people were tucking in for eight hours. Today, the average North American adult sleeps a paltry six-and-a-half hours every night. This is often blamed on our devices, which do play a major role. But Crary argues that, interrelatedly, the forces of twenty-first-century capitalism have shown an obsessive enthusiasm for destroying sleep. When he passed away this week at the age of ninety-four, the singer, songwriter, and actor Charles Aznavour was still touring. He was a living link to the golden age of French chanson. As a young man, he had been maligned as short and ugly, an immigrant with a hoarse voice, but he became a protégée of Édith Piaf, and then a global star in his own right. While his success in the anglophone world never equaled his renown in other countries, he was, by any reckoning, one of the twentieth century’s most popular entertainers, often referred to as the French Sinatra (Aznavour sang with Sinatra on the latter’s Duets record). He sang in five languages, appeared in at least thirty films, wrote somewhere in the vicinity of a thousand songs, and sold hundreds of millions of records worldwide.

When he passed away this week at the age of ninety-four, the singer, songwriter, and actor Charles Aznavour was still touring. He was a living link to the golden age of French chanson. As a young man, he had been maligned as short and ugly, an immigrant with a hoarse voice, but he became a protégée of Édith Piaf, and then a global star in his own right. While his success in the anglophone world never equaled his renown in other countries, he was, by any reckoning, one of the twentieth century’s most popular entertainers, often referred to as the French Sinatra (Aznavour sang with Sinatra on the latter’s Duets record). He sang in five languages, appeared in at least thirty films, wrote somewhere in the vicinity of a thousand songs, and sold hundreds of millions of records worldwide. In 2017, scientists in Australia

In 2017, scientists in Australia  If we keep burning coal and petroleum to power our society, we’re cooked — and a lot faster than we thought. The United Nations scientific panel on climate change issued

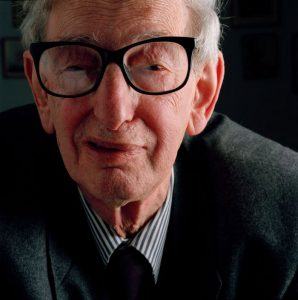

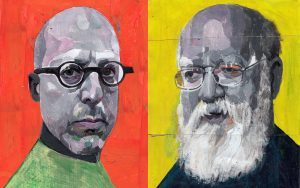

If we keep burning coal and petroleum to power our society, we’re cooked — and a lot faster than we thought. The United Nations scientific panel on climate change issued  Caruso: [Dan,] you have famously argued that freedom evolves and that humans, alone among the animals, have evolved minds that give us free will and moral responsibility. I, on the other hand, have argued that what we do and the way we are is ultimately the result of factors beyond our control, and that because of this we are never morally responsible for our actions, in a particular but pervasive sense – the sense that would make us truly deserving of blame and praise, punishment and reward. While these two views appear to be at odds with each other, one of the things I would like to explore in this conversation is how far apart we actually are. I suspect that we may have more in common than some think – but I could be wrong. To begin, can you explain what you mean by ‘free will’ and why you think humans alone have it?

Caruso: [Dan,] you have famously argued that freedom evolves and that humans, alone among the animals, have evolved minds that give us free will and moral responsibility. I, on the other hand, have argued that what we do and the way we are is ultimately the result of factors beyond our control, and that because of this we are never morally responsible for our actions, in a particular but pervasive sense – the sense that would make us truly deserving of blame and praise, punishment and reward. While these two views appear to be at odds with each other, one of the things I would like to explore in this conversation is how far apart we actually are. I suspect that we may have more in common than some think – but I could be wrong. To begin, can you explain what you mean by ‘free will’ and why you think humans alone have it?