Category: Recommended Reading

The Forgotten Father of American Conservatism

Matthew Continetti at The Atlantic:

The Conservative Mind has provided generations of conservatives a sense of history and point of view. Where before conservatives had felt isolated, on the margins of political and cultural debate, they now could take their place in a great chain of thinkers, beginning in the modern era with Edmund Burke and continuing to the present. Kirk’s gallery of heroes was as idiosyncratic as his personality, grouping Brits with Americans, reactionaries with reformers, Confederates with Yankees. His chapters on John Randolph and John Calhoun, defenders of the slave power, discomfit contemporary readers, yet he also greatly admired Abraham Lincoln. Kirk was as critical of capitalism—he reminded audiences that it was a Marxist term—as he was of socialism. As he put it later: “The intellectual heirs of Burke, and the conservative interest generally, did battle on two fronts: against the successors of the Jacobins, with their ‘armed doctrine’; and against the economists of Manchester, with their reliance upon the nexus of cash payment.”

more here.

The Literature of Inequality

Nicolas Léger at Eurozine:

Two bodies of work, both particularly symptomatic of the bankruptcy of egalitarianism and the triumph of individualism against a background of Western resignation, have been hugely successful both in France and elsewhere (a sign that they resonate deeply in an era of globalization and crisis). Virginie Despentes and Michel Houellebecq, each in their idiosyncratic way, do not just describe these social changes and their effects, but have also set about identifying their horizons, or the possibilities of survival beyond them. They take the way the naturalist novel depicts society and adapt it to suit their purposes, adding imagery and narrative techniques borrowed from a strand of English-language literature hitherto referred to condescendingly as ‘popular’. But it is precisely these influences, the product of a counterculture born out of globalization and the twentieth century, that enable them to bear the weight of the singularities of our contemporary modernity: science fiction in in Houellebecq’s Atomised (1998), futuristic dystopian narrative in his Submission (2015), or crime noir in Despentes’s Vernon Subutex (2015–2017).

Two bodies of work, both particularly symptomatic of the bankruptcy of egalitarianism and the triumph of individualism against a background of Western resignation, have been hugely successful both in France and elsewhere (a sign that they resonate deeply in an era of globalization and crisis). Virginie Despentes and Michel Houellebecq, each in their idiosyncratic way, do not just describe these social changes and their effects, but have also set about identifying their horizons, or the possibilities of survival beyond them. They take the way the naturalist novel depicts society and adapt it to suit their purposes, adding imagery and narrative techniques borrowed from a strand of English-language literature hitherto referred to condescendingly as ‘popular’. But it is precisely these influences, the product of a counterculture born out of globalization and the twentieth century, that enable them to bear the weight of the singularities of our contemporary modernity: science fiction in in Houellebecq’s Atomised (1998), futuristic dystopian narrative in his Submission (2015), or crime noir in Despentes’s Vernon Subutex (2015–2017).

more here.

Remembering Andre Dubus

Tobias Wolff at The American Scholar:

“Voices from the Moon” is my favorite of all Andre Dubus’s stories and novellas. It concerns itself unabashedly and unsentimentally with love—the love of parents for their children, of men for women and women for women, of a boy’s love for God, and a teenage girl’s love for cigarettes. The story is too rich to paraphrase, but in brief, a divorced man has fallen in love with his son’s ex-wife, and she with him. They mean to live together. The family is shaken to its roots by the apparent betrayals involved, and not least by the social impropriety of such an arrangement—its radical flouting of convention. Yet as the story proceeds we see its people react not with the sort of virtuous outrage we might expect, but with hard-won understanding, generosity, forgiveness, and love. In essence, the family members declare their independence from submissive concern or embarrassment about how things might look to others, finding freedom in their refusal to let their lives be shaped by the expectations and decorums of social custom. Sensational as the premise of the story may be—it was inspired by a newspaper article Dubus happened upon—he illuminates his people’s lives not by heating up the drama inherent in their situation, but by allowing each of them quiet, ordinary moments in which to reveal themselves, to profound, extraordinary effect. It is altogether Dubus’s strangest, most moving and beautiful piece of work.

“Voices from the Moon” is my favorite of all Andre Dubus’s stories and novellas. It concerns itself unabashedly and unsentimentally with love—the love of parents for their children, of men for women and women for women, of a boy’s love for God, and a teenage girl’s love for cigarettes. The story is too rich to paraphrase, but in brief, a divorced man has fallen in love with his son’s ex-wife, and she with him. They mean to live together. The family is shaken to its roots by the apparent betrayals involved, and not least by the social impropriety of such an arrangement—its radical flouting of convention. Yet as the story proceeds we see its people react not with the sort of virtuous outrage we might expect, but with hard-won understanding, generosity, forgiveness, and love. In essence, the family members declare their independence from submissive concern or embarrassment about how things might look to others, finding freedom in their refusal to let their lives be shaped by the expectations and decorums of social custom. Sensational as the premise of the story may be—it was inspired by a newspaper article Dubus happened upon—he illuminates his people’s lives not by heating up the drama inherent in their situation, but by allowing each of them quiet, ordinary moments in which to reveal themselves, to profound, extraordinary effect. It is altogether Dubus’s strangest, most moving and beautiful piece of work.

more here.

Why Doesn’t Ancient Fiction Talk About Feelings?

Julie Sedivy in Nautilus:

Reading medieval literature, it’s hard not to be impressed with how much the characters get done—as when we read about King Harold doing battle in one of the Sagas of the Icelanders, written in about 1230. The first sentence bristles with purposeful action: “King Harold proclaimed a general levy, and gathered a fleet, summoning his forces far and wide through the land.” By the end of the third paragraph, the king has launched his fleet against a rebel army, fought numerous battles involving “much slaughter in either host,” bound up the wounds of his men, dispensed rewards to the loyal, and “was supreme over all Norway.” What the saga doesn’t tell us is how Harold felt about any of this, whether his drive to conquer was fueled by a tyrannical father’s barely concealed contempt, or whether his legacy ultimately surpassed or fell short of his deepest hopes.

Reading medieval literature, it’s hard not to be impressed with how much the characters get done—as when we read about King Harold doing battle in one of the Sagas of the Icelanders, written in about 1230. The first sentence bristles with purposeful action: “King Harold proclaimed a general levy, and gathered a fleet, summoning his forces far and wide through the land.” By the end of the third paragraph, the king has launched his fleet against a rebel army, fought numerous battles involving “much slaughter in either host,” bound up the wounds of his men, dispensed rewards to the loyal, and “was supreme over all Norway.” What the saga doesn’t tell us is how Harold felt about any of this, whether his drive to conquer was fueled by a tyrannical father’s barely concealed contempt, or whether his legacy ultimately surpassed or fell short of his deepest hopes.

Jump ahead about 770 years in time, to the fiction of David Foster Wallace. In his short story “Forever Overhead,” the 13-year-old protagonist takes 12 pages to walk across the deck of a public swimming pool, wait in line at the high diving board, climb the ladder, and prepare to jump. But over these 12 pages, we are taken into the burgeoning, buzzing mind of a boy just erupting into puberty—our attention is riveted to his newly focused attention on female bodies in swimsuits, we register his awareness that others are watching him as he hesitates on the diving board, we follow his undulating thoughts about whether it’s best to do something scary without thinking about it or whether it’s foolishly dangerous not to think about it. These examples illustrate Western literature’s gradual progression from narratives that relate actions and events to stories that portray minds in all their meandering, many-layered, self-contradictory complexities. I’d often wondered, when reading older texts: Weren’t people back then interested in what characters thought and felt?

More here.

To write about politics in Pakistan, you have to go abroad

Claire Armistead in The Guardian:

They put GPS chips in pets and migratory birds now. How can someone flying around in a 65-million-dollar machine get lost?” With these words – spoken by a US airman who has just crashed his jet in an unnamed desert – Mohammed Hanif upends his own premise in the opening pages of his new novel. It is a typically bold manoeuvre from a satirical writer who was himself once a pilot – “a really bad one” – and whose work is full of references to military hardware. His Booker-longlisted debut A Case of Exploding Mangoes placed a cart of the fruit alongside Pakistan’s president Zia ul-Haq on a doomed C-130 Hercules; his second told of a spirited convent nurse married off on a nuclear submarine. But jokey though his fiction appears, its political mission is Orwellian – his work is underpinned by a sense of a corrupt world that is constantly embattled. “I think I must have been at high school when the Afghan war started, so we grew up with these kinds of conflicts, and then they started to replicate themselves around the world. These wars never end. The attention just moves somewhere else,” says the 53-year-old novelist, journalist and occasional playwright.

They put GPS chips in pets and migratory birds now. How can someone flying around in a 65-million-dollar machine get lost?” With these words – spoken by a US airman who has just crashed his jet in an unnamed desert – Mohammed Hanif upends his own premise in the opening pages of his new novel. It is a typically bold manoeuvre from a satirical writer who was himself once a pilot – “a really bad one” – and whose work is full of references to military hardware. His Booker-longlisted debut A Case of Exploding Mangoes placed a cart of the fruit alongside Pakistan’s president Zia ul-Haq on a doomed C-130 Hercules; his second told of a spirited convent nurse married off on a nuclear submarine. But jokey though his fiction appears, its political mission is Orwellian – his work is underpinned by a sense of a corrupt world that is constantly embattled. “I think I must have been at high school when the Afghan war started, so we grew up with these kinds of conflicts, and then they started to replicate themselves around the world. These wars never end. The attention just moves somewhere else,” says the 53-year-old novelist, journalist and occasional playwright.

Never-ending war is the location of Red Birds, albeit one in which the bombing has mysteriously stopped. The lost airman, Major Ellie, is transported to a refugee camp by a young boy who discovers him while scouring the desert for his injured dog. The boy, Momo, is the book’s most vivid creation – an adolescent huckster who drives a “jeep Cherokee with a fat, fading USAid logo” and is hell-bent on rescuing his older brother from a sinister military base known as The Hangar. “People ask where it’s set and I say it’s set in my head,” says Hanif, who riffs that he had hoped to write a novel in which bad things can’t happen. “I know a lot of people who are very happy with their lives – who go around doing good things, or believing that they are doing good things.”

More here.

Friday Poem

Seeking The Hook

with its barbed point digging

into the soft palate behind my lower teeth

I am dragged along the mud and rock-strewn

bottom for forty feet, then pulled up

drawn toward the light as I twist and

yank my head side to side and the hook

lodges deeper in my mouth I taste

the blood a silent cry goes up through

my skull and it is all so quick I see

the surface a hand the light overwhelms

me, and I lunge a last time with the hook

ripping across my lips and I’m free

suddenly falling back gasping through

air then slipping beneath the surface

into the dim, green sweetness and

the flesh of my mouth throbbing water

flowing through me and yet slowly,

beyond thought or even the will

to survive, I feel myself turn and

go back, seeking the hook and it

is there again, waiting for me,

rigid and tiny, the hidden barb

like a beautiful lie, too powerful

for me to resist, so that later when

they lift me, strip me, tear my guts

out and present me cooked and

spread open, I will believe I am being

honored like a new king.

Lou Lipsitz

from Seeking the Hook

Signal Books, 1997

Thursday, October 18, 2018

Belated Thoughts on the Avital Ronell Scandal

Justin E. H. Smith in his blog:

In the five years since I moved to Paris as an American philosopher working within the French system, my disdain for what Americans know as ‘French theory’, and particularly for the American reception of it, has only deepened. Sometimes I find it burdensome to be pursuing my work so close to the belly of this noisome beast (my campus of the University of Paris lies on the city’s southeastern border, while the belly, properly anatomically speaking, is two RER stops to the west (its external gonads are up in St. Denis)), but for the most part I am happy to process this unanticipated twist in my career as one of my life’s animating ironies, and to milk this irony for insights that I would not be able to come by if I were either geographically far away from this intellectual culture, or a fawning convert to it.

In the five years since I moved to Paris as an American philosopher working within the French system, my disdain for what Americans know as ‘French theory’, and particularly for the American reception of it, has only deepened. Sometimes I find it burdensome to be pursuing my work so close to the belly of this noisome beast (my campus of the University of Paris lies on the city’s southeastern border, while the belly, properly anatomically speaking, is two RER stops to the west (its external gonads are up in St. Denis)), but for the most part I am happy to process this unanticipated twist in my career as one of my life’s animating ironies, and to milk this irony for insights that I would not be able to come by if I were either geographically far away from this intellectual culture, or a fawning convert to it.

Other than an isolated sentence here or there, I’ve never read Derrida, and never will. But then again there are countless other former students of the École Normale Supérieure, who spent their later lives riffing in various ways on the texts and authors they learned about at school, but who didn’t stumble, like Chance the Gardener, into some absurd American fame they could neither control nor understand, and I’ll never read them either. Does any American academic think there’s a serious gap in our reading if we haven’t tackled, say, Jean Hyppolite? Of course not.

More here.

How the Trust Trap Perpetuates Inequality

Bo Rothstein in Scientific American:

An abundance of social science research indicates that high economic inequality comes along with several undesirable outcomes, such as higher levels of violence and lower levels of health, happiness and satisfaction with life. But inequality has been rising in almost all developed countries since the 1970s, which raises an important question. If high inequality is detrimental to the well-being of a large majority of the populace and if democracy is about realizing “the will of the people,” why has inequality been allowed to increase in most democracies? Put differently, if most people would benefit from enhancing equality, why have voters not elected politicians who would implement policies to do that? This is one of the most significant paradoxes of our time.

An abundance of social science research indicates that high economic inequality comes along with several undesirable outcomes, such as higher levels of violence and lower levels of health, happiness and satisfaction with life. But inequality has been rising in almost all developed countries since the 1970s, which raises an important question. If high inequality is detrimental to the well-being of a large majority of the populace and if democracy is about realizing “the will of the people,” why has inequality been allowed to increase in most democracies? Put differently, if most people would benefit from enhancing equality, why have voters not elected politicians who would implement policies to do that? This is one of the most significant paradoxes of our time.

Scholars provide a variety of explanations: Some point to the limited foresight, knowledge and rationality of voters. Others argue that the increased power of money in politics has prevented politicians who would launch redistributive policies from coming to power. A third view is that economic changes have weakened the power of trade unions, which used to be a strong force supporting equality. A fourth argument is that the political agenda has changed.

More here.

Nico Muhly on the Drama of Bringing His New Opera to the Met

Nico Muhly in the New York Times:

“Marnie,” my new opera, which has its American premiere on Friday at the Metropolitan Opera, is about a woman who lies, steals, gets caught and is forced to marry a man who sexually assaults her. It’s delicate material — to say the least — and deeply plot-driven, and the dramatic structure has to be airtight to allow room for expressive musicality.

“Marnie,” my new opera, which has its American premiere on Friday at the Metropolitan Opera, is about a woman who lies, steals, gets caught and is forced to marry a man who sexually assaults her. It’s delicate material — to say the least — and deeply plot-driven, and the dramatic structure has to be airtight to allow room for expressive musicality.

The director, Michael Mayer, called me with the idea for a “Marnie” opera five years ago. The story is most famous from the Hitchcock film, but we found that the 1961 Winston Graham novel on which it’s based was a far richer source of psychological tension and freed us from any visual or musical entanglements with the movie. That first notion blossomed into a wonderful libretto by Nicholas Wright, which then turned into a giant stack of manuscript.

Now, in the days before opening, among the orchestra, the chorus, the principal singers, the stage crew, spot ops, dressers, wig-makers, etc., there are hundreds of people reacting to this document; it’s a huge, thrilling, anxiety-producing setup.

More here.

Gad Saad explains Evolutionary Psychology

The Erotics of Cy Twombly

Catherine Lacey at The Paris Review:

Early in Chalk: The Art and Erasure of Cy Twombly, author Joshua Rivkin confesses that the book “is not a biography. This is something, I hope, stranger and more personal.” What, a reader may wonder, could be more personal than a biography? Chalk is one answer to that riddle.

Early in Chalk: The Art and Erasure of Cy Twombly, author Joshua Rivkin confesses that the book “is not a biography. This is something, I hope, stranger and more personal.” What, a reader may wonder, could be more personal than a biography? Chalk is one answer to that riddle.

Cy Twombly, a prominent abstract artist whose popularity has only grown since his death in 2011, is best known for his large, abstract paintings—“passionate splashes of color … curves of white chalk looping through darkness.” Rivkin describes the artist’s work as an actualization of “the bewildering slipstream between thinking and feeling.” Twombly’s most staunch admirers are ecstatically unnerved by his canvases; a woman once spontaneously kissed one painting, leaving behind a lipsticked print. (She was, as lovers often are, unrepentant.) But, outside the art world, Twombly’s messy, seemingly thoughtless style inspired confusion and disdain. His scratchy, hectic paintings have led the unimaginative to shrug, “My kid could do that.”

more here.

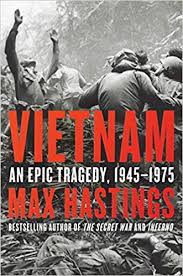

Vietnam: An Epic Tragedy

Christopher Goscha at Literary Review:

According to Max Hastings, it was ‘an epic tragedy’ for those who lived through it. From start to finish, the wars for Vietnam sowed death and destruction across the land. Starting with the outbreak of the French war with Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh in 1945 and ending with the inglorious American evacuation from Saigon in 1975, Hastings focuses on how combatants and civilians experienced war. He draws upon an impressive range of sources to take the reader into the line of fire. Through vivid descriptions and moving prose, he shows us the suffering, trauma and death that the French and especially American campaigns inflicted upon the civilians and soldiers on all sides who found themselves caught up in what turned into a conflagration of mind-boggling violence.

According to Max Hastings, it was ‘an epic tragedy’ for those who lived through it. From start to finish, the wars for Vietnam sowed death and destruction across the land. Starting with the outbreak of the French war with Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh in 1945 and ending with the inglorious American evacuation from Saigon in 1975, Hastings focuses on how combatants and civilians experienced war. He draws upon an impressive range of sources to take the reader into the line of fire. Through vivid descriptions and moving prose, he shows us the suffering, trauma and death that the French and especially American campaigns inflicted upon the civilians and soldiers on all sides who found themselves caught up in what turned into a conflagration of mind-boggling violence.

High politics is also here. To his credit, Hastings weaves into his narrative a more critical account of the communist regime than many authors have been willing to do.

more here.

Isaiah Berlin: Against Dogma

Henry Hardy at the TLS:

Berlin’s absorption in the history of ideas dates back almost to the beginning of his academic career. In 1933 he was commissioned to write a book on Karl Marx, which was published in 1939 and is still in print today. His reading of Marx and Marx’s predecessors, especially the philosophers of the Enlightenment, and even more their opponents, the “Counter-Enlightenment” as he called them, fuelled his thought for the rest of his life.

Berlin’s absorption in the history of ideas dates back almost to the beginning of his academic career. In 1933 he was commissioned to write a book on Karl Marx, which was published in 1939 and is still in print today. His reading of Marx and Marx’s predecessors, especially the philosophers of the Enlightenment, and even more their opponents, the “Counter-Enlightenment” as he called them, fuelled his thought for the rest of his life.

In the Enlightenment he finds the most complete expression of a philosophical view that he traces back at least to Plato: the view that, properly managed and understood, human life and society can be harmonious and coherent, all moral and political questions finally answered, all values frictionlessly reconciled, and conflict and misery eliminated. (The enormous implausibility of such a view testifies to the ability of philosophers to espouse beliefs known to be false by anyone with a modicum of common sense.) In the eighteenth century this belief was reinforced by the success of the scientific revolution, which created the expectation that human affairs, like the natural world, could be explained in scientific terms.

more here.

What’s Your Story?

Lisa Bortolotti in IAI News:

Who am I? It is difficult for me to recognise myself in a photo taken when I was 5 and to identify with the thoughts I had when I was 16. But I can do that because I have a ‘sense of self’ which includes beliefs about myself that address two basic questions: which person I am and what type of person I am. The first question can be answered by reference to my life history (e.g., when I was born, who my parents are, what my job is) and the second question concerns my personality and dispositions (e.g., whether I am loyal, whether I am good at playing volleyball, whether I like Russian literature). How do I keep all the relevant information about myself together to attain a sense of self? Well, I do what humans do best, tell stories. Self-narratives are the means by which I establish continuity between my past, present, and future experiences and impose some coherence on my disparate traits and features. I am not alone in doing this: we all create stories that make sense of the experiences we remember and connect our life events in some meaningful way using the literary devices stories have, plots helping us see how some events follow from other events and twists acknowledging surprising developments that have a big effect on the course of our lives.

Who am I? It is difficult for me to recognise myself in a photo taken when I was 5 and to identify with the thoughts I had when I was 16. But I can do that because I have a ‘sense of self’ which includes beliefs about myself that address two basic questions: which person I am and what type of person I am. The first question can be answered by reference to my life history (e.g., when I was born, who my parents are, what my job is) and the second question concerns my personality and dispositions (e.g., whether I am loyal, whether I am good at playing volleyball, whether I like Russian literature). How do I keep all the relevant information about myself together to attain a sense of self? Well, I do what humans do best, tell stories. Self-narratives are the means by which I establish continuity between my past, present, and future experiences and impose some coherence on my disparate traits and features. I am not alone in doing this: we all create stories that make sense of the experiences we remember and connect our life events in some meaningful way using the literary devices stories have, plots helping us see how some events follow from other events and twists acknowledging surprising developments that have a big effect on the course of our lives.

Self-narratives, as all narratives, are to some extent fictional. In order to be able to tell a meaningful and exciting story about ourselves, we need to take some creative licences with the facts. We may consciously embellish some chapters of our stories by adding or omitting some detail. But other distortions of reality are just part and parcel of the way we tend to think about ourselves and are the outcome of biases that we are not fully aware of. For instance, we neglect evidence of failure, concentrating on evidence of good performance and emphasising our contribution to successful enterprises, so as to make ourselves into the heroes our stories deserve.

More here.

Cuttlefish wear their thoughts on their skin

Sara Reardon in Nature:

Cuttlefish are masters at altering their appearance to blend into their surroundings. But the cephalopods can no longer hide their inner thoughts, thanks to a technique that infers a cuttlefish’s brain activity by tracking the ever-changing patterns on its skin. The findings, published in Nature on 17 October1, could help researchers to better understand how the brain controls behaviour. The cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis) camouflages itself by contracting the muscles around tiny, coloured skin cells called chromatophores. The cells come in several colours and act as pixels across the cuttlefish’s body, changing their size to alter the pattern on the animal’s skin. The cuttlefish doesn’t always conjure up an exact match for its background. It can also blanket itself in stripes, rings, mottles or other complex patterns to make itself less noticeable to predators. “On any background, especially a coral reef, it can’t look like a thousand things,” says Roger Hanlon, a cephalopod biologist at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Chicago, Illinois. “Camouflage is about deceiving the visual system.”

Cuttlefish are masters at altering their appearance to blend into their surroundings. But the cephalopods can no longer hide their inner thoughts, thanks to a technique that infers a cuttlefish’s brain activity by tracking the ever-changing patterns on its skin. The findings, published in Nature on 17 October1, could help researchers to better understand how the brain controls behaviour. The cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis) camouflages itself by contracting the muscles around tiny, coloured skin cells called chromatophores. The cells come in several colours and act as pixels across the cuttlefish’s body, changing their size to alter the pattern on the animal’s skin. The cuttlefish doesn’t always conjure up an exact match for its background. It can also blanket itself in stripes, rings, mottles or other complex patterns to make itself less noticeable to predators. “On any background, especially a coral reef, it can’t look like a thousand things,” says Roger Hanlon, a cephalopod biologist at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Chicago, Illinois. “Camouflage is about deceiving the visual system.”

To better understand how cuttlefish create these patterns across their bodies, neuroscientist Gilles Laurent at the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research in Frankfurt, Germany, and his collaborators built a system of 20 video cameras to film cuttlefish at 60 frames per second as they swam around their enclosures. The cameras captured the cuttlefish changing colour as they passed by backgrounds such as gravel or printed images that the researchers placed in the tanks. The recording began soon after the cuttlefish hatched, and continued for weeks. Laurent’s team developed video-processing techniques to identify tens of thousands of individual chromatophores on each cuttlefish, including cells that emerged as the animal grew larger over time. The team used statistical tools to determine how different chromatophores act in synchrony to change the animal’s overall skin patterns. Previous studies have shown that each chromatophore is controlled by multiple motor neurons that reach from the brain to muscles in the skin, and that each motor neuron controls several chromatophores. These in turn group together into larger motor systems that create patterns across the cuttlefish’s body.

More here.

Thursday Poem

Gift

He said: Here is my soul.

I did not want his soul

but I am a southerner

and very polite.

I took it lightly

as it was offered. But did not

chain it down.

I loved it and tended

it. I would hand it back

as good as new.

He said: How dare you want

my soul! Give it back!

How greedy you are!

It is a trait

I had not noticed

before!

I said: But your soul

never left you. It was only

a heavy thought from

your childhood

passed to me for safekeeping.

But he never believed me.

Until the end

he called me possessive

and held his soul

so tightly

it shrank

to fit his hand.

Alice Walker

from Her Blue Body Everything We Know

Harvest Books

Wednesday, October 17, 2018

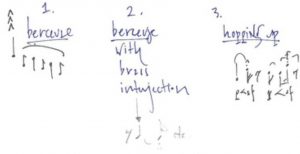

Nico Muhly: How I Write Music

Nico Muhly in the London Review of Books:

I avoid reading accounts of other composers’ ways of working. I’ve only ever been disappointed by stories of their abusive and antagonistic relationships with the people they’re close to, or, in the case of historical figures, wild speculation about their mental states or marital problems or excessive drinking. When I talk to my colleagues, I am of course happy to hear about their sex dramas and squabbles with the landlord, but what I really want is shop talk: what kinds of pencil are you using? How are you finding this particular piece of software? Do you watch the news while you work? I find these details telling.

I avoid reading accounts of other composers’ ways of working. I’ve only ever been disappointed by stories of their abusive and antagonistic relationships with the people they’re close to, or, in the case of historical figures, wild speculation about their mental states or marital problems or excessive drinking. When I talk to my colleagues, I am of course happy to hear about their sex dramas and squabbles with the landlord, but what I really want is shop talk: what kinds of pencil are you using? How are you finding this particular piece of software? Do you watch the news while you work? I find these details telling.

For me, every project has three clearly defined phases: the scheming and planning; the writing of actual notes; the editing. The planning process almost entirely excludes, by design, notes and rhythms. When I was a twenty-year-old student at Juilliard, I constantly had hundreds of tiny, brilliant ideas, each lasting about five seconds, and instead of learning to use them, I’d just throw them at the wall in some order and the result would be a sparkling and disorganised mess, a free-form string of disjointed but attractive thoughts. My teacher set out to fix this problem, and taught me a method of planning I still use to this day. With every piece, no matter its forces or length, the first thing I do is to map out its itinerary, from the simplest, bird’s-eye view to more detailed questions: what are the textures and lines that form the piece’s musical economy? Does it develop linearly, or vertically? Are there moments of dense saturation – the whole orchestra playing at once – and are those offset by moments of zoomed-in simplicity: a single flute, or a single viola pitted against the timpani, yards and yards away?

More here.

Graduate Student Solves Quantum Verification Problem

Erica Klarreich in Quanta:

In the spring of 2017, Urmila Mahadev found herself in what most graduate students would consider a pretty sweet position. She had just solved a major problem in quantum computation, the study of computers that derive their power from the strange laws of quantum physics. Combined with her earlier papers, Mahadev’s new result, on what is called blind computation, made it “clear she was a rising star,” said Scott Aaronson, a computer scientist at the University of Texas, Austin.

In the spring of 2017, Urmila Mahadev found herself in what most graduate students would consider a pretty sweet position. She had just solved a major problem in quantum computation, the study of computers that derive their power from the strange laws of quantum physics. Combined with her earlier papers, Mahadev’s new result, on what is called blind computation, made it “clear she was a rising star,” said Scott Aaronson, a computer scientist at the University of Texas, Austin.

Mahadev, who was 28 at the time, was already in her seventh year of graduate school at the University of California, Berkeley — long past the stage when most students become impatient to graduate. Now, finally, she had the makings of a “very beautiful Ph.D. dissertation,” said Umesh Vazirani, her doctoral adviser at Berkeley.

But Mahadev did not graduate that year. She didn’t even consider graduating. She wasn’t finished.

For more than five years, she’d had a different research problem in her sights, one that Aaronson called “one of the most basic questions you can ask in quantum computation.” Namely: If you ask a quantum computer to perform a computation for you, how can you know whether it has really followed your instructions, or even done anything quantum at all?

More here.

A Sociologist Examines the “White Fragility” That Prevents White Americans from Confronting Racism

Katy Waldman in The New Yorker:

In more than twenty years of running diversity-training and cultural-competency workshops for American companies, the academic and educator Robin DiAngelo has noticed that white people are sensationally, histrionically bad at discussing racism. Like waves on sand, their reactions form predictable patterns: they will insist that they “were taught to treat everyone the same,” that they are “color-blind,” that they “don’t care if you are pink, purple, or polka-dotted.” They will point to friends and family members of color, a history of civil-rights activism, or a more “salient” issue, such as class or gender. They will shout and bluster. They will cry. In 2011, DiAngelo coined the term “white fragility” to describe the disbelieving defensiveness that white people exhibit when their ideas about race and racism are challenged—and particularly when they feel implicated in white supremacy. Why, she wondered, did her feedback prompt such resistance, as if the mention of racism were more offensive than the fact or practice of it?

In more than twenty years of running diversity-training and cultural-competency workshops for American companies, the academic and educator Robin DiAngelo has noticed that white people are sensationally, histrionically bad at discussing racism. Like waves on sand, their reactions form predictable patterns: they will insist that they “were taught to treat everyone the same,” that they are “color-blind,” that they “don’t care if you are pink, purple, or polka-dotted.” They will point to friends and family members of color, a history of civil-rights activism, or a more “salient” issue, such as class or gender. They will shout and bluster. They will cry. In 2011, DiAngelo coined the term “white fragility” to describe the disbelieving defensiveness that white people exhibit when their ideas about race and racism are challenged—and particularly when they feel implicated in white supremacy. Why, she wondered, did her feedback prompt such resistance, as if the mention of racism were more offensive than the fact or practice of it?

In a new book, “White Fragility,” DiAngelo attempts to explicate the phenomenon of white people’s paper-thin skin. She argues that our largely segregated society is set up to insulate whites from racial discomfort, so that they fall to pieces at the first application of stress—such as, for instance, when someone suggests that “flesh-toned” may not be an appropriate name for a beige crayon.

More here.