Tyler Cowen at Bloomberg:

Imagine the perfect political and intellectual weapon. It would disable your adversaries by preoccupying them with their own vanities and squabbles, a bit like a drug so good that users focus on the high and stop everything else they are doing.

Such a weapon exists: It is called political correctness. But it is not a weapon against white men or conservatives, as is frequently alleged; rather, it is a weapon against the American left. To put it simply, the American left has been hacked, and it is now running in a circle of its own choosing, rather than focusing on electoral victories or policy effectiveness. Too many segments of the Democratic Party are self-righteously talking about identity politics, and they are letting other priorities slip.

More here.

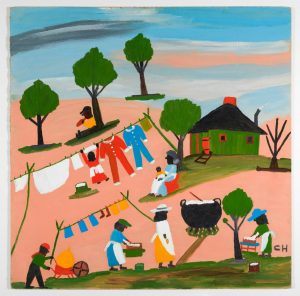

She was born just 20 years after the Civil War. Her grandparents were enslaved. And after decades of working in a storied Louisiana plantation, Clementine Hunter picked up a brush and began depicting African-American life in the South, turning out thousands of paintings first sold for less than a dollar that are now fetching thousands. Often called the black Grandma Moses, for the simplicity of her work and her late life enthusiasm for it, the artist, who died in 1988 at age 101, is being celebrated in an exhibition held in the Rhimes Family Foundation Visual Art Gallery at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

She was born just 20 years after the Civil War. Her grandparents were enslaved. And after decades of working in a storied Louisiana plantation, Clementine Hunter picked up a brush and began depicting African-American life in the South, turning out thousands of paintings first sold for less than a dollar that are now fetching thousands. Often called the black Grandma Moses, for the simplicity of her work and her late life enthusiasm for it, the artist, who died in 1988 at age 101, is being celebrated in an exhibition held in the Rhimes Family Foundation Visual Art Gallery at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. Nine pints, give or take. That’s how much blood you have, surging in time to “the old brag”, as Sylvia Plath put it, of your heart. Although for

Nine pints, give or take. That’s how much blood you have, surging in time to “the old brag”, as Sylvia Plath put it, of your heart. Although for  Paul Allen, one of my oldest friends and the first business partner I ever had, died yesterday. I want to extend my condolences to his sister, Jody, his extended family, and his many friends and colleagues around the world.

Paul Allen, one of my oldest friends and the first business partner I ever had, died yesterday. I want to extend my condolences to his sister, Jody, his extended family, and his many friends and colleagues around the world. Imprisoned in the fortress of Taureau, a tiny thumb of rock off the windswept coast of Brittany, the French revolutionary Louis-Auguste Blanqui gazed toward the stars. He had been locked up for his role in the socialist movement that would lead to the Paris Commune of 1871. As Blanqui looked up at the night sky, he found comfort in the possibility of other worlds. While life on Earth is fleeting, he wrote in Eternity by the Stars(1872), we might take solace in the notion that myriad replicas of our planet are brimming with similar creatures – that all events, he said, ‘that have taken place or that are yet to take place on our globe, before it dies, take place in exactly the same way on its billions of duplicates’. Might certain souls be imprisoned on these faraway worlds, too? Perhaps. But Blanqui held out hope that, through chance mutations, those who are unjustly jailed down here on Earth might there walk free.

Imprisoned in the fortress of Taureau, a tiny thumb of rock off the windswept coast of Brittany, the French revolutionary Louis-Auguste Blanqui gazed toward the stars. He had been locked up for his role in the socialist movement that would lead to the Paris Commune of 1871. As Blanqui looked up at the night sky, he found comfort in the possibility of other worlds. While life on Earth is fleeting, he wrote in Eternity by the Stars(1872), we might take solace in the notion that myriad replicas of our planet are brimming with similar creatures – that all events, he said, ‘that have taken place or that are yet to take place on our globe, before it dies, take place in exactly the same way on its billions of duplicates’. Might certain souls be imprisoned on these faraway worlds, too? Perhaps. But Blanqui held out hope that, through chance mutations, those who are unjustly jailed down here on Earth might there walk free. I READ DENNIS COOPER for the first time when I was a 23-year-old student in an MFA program. No professor assigned him to me. Cooper’s language is blunt, often sounding as though spoken through a veil of intoxicants, and his tales of insecure gay teenagers and the men who castrate, murder, disembowel, and cannibalize them would have been a hard pitch to those who had come to grad school to learn how to sell their manuscripts. The only other openly gay student in my writing cohort, K., recommended the George Miles Cycle (1989–2000) and God Jr. (2005), his voice catching as we talked. He was afraid to read The Sluts (2004), because he had recently been through a breakup and he was concerned that a narrative about a group of middle-aged men who become obsessed with a prostitute named Brad, using internet chat rooms to describe his torture and death, might mar his sense of the possibilities of single life as a sexually active gay person.

I READ DENNIS COOPER for the first time when I was a 23-year-old student in an MFA program. No professor assigned him to me. Cooper’s language is blunt, often sounding as though spoken through a veil of intoxicants, and his tales of insecure gay teenagers and the men who castrate, murder, disembowel, and cannibalize them would have been a hard pitch to those who had come to grad school to learn how to sell their manuscripts. The only other openly gay student in my writing cohort, K., recommended the George Miles Cycle (1989–2000) and God Jr. (2005), his voice catching as we talked. He was afraid to read The Sluts (2004), because he had recently been through a breakup and he was concerned that a narrative about a group of middle-aged men who become obsessed with a prostitute named Brad, using internet chat rooms to describe his torture and death, might mar his sense of the possibilities of single life as a sexually active gay person. Whilst Banerjee recognises the beauty and utility of traditional forms, she plays with a multitude of poetic and thematic forms, pirouetting from the profane to the sacred, the mundane to the sublime, the broadly public to the deeply profound and personal with the ease of a virtuoso. Haiku is placed alongside sonnets and ghazals, interspersed with erasure, hymns, mistranslations and vers-libre to give birth to different metronomic languages and rhythms that create a new voice. Banerjee´s linguistic artfulness resides in her ability to translate all these foreign words, cultures, and geographies into a coherent language of aesthetic, philosophical, and political portent. As seen in the haiku “A Waters Sound” where the entrenchment of social conventions and power structures is metaphorically conveyed by the image of a deep, leaf-grown well from which potential young feminists are blocked from jumping out by the wire-meshed sky. The Japanese ideograms of the original poem drip silently down the face of the page, creating and holding a meditative space for the reader to ruminate upon the depth of the well.

Whilst Banerjee recognises the beauty and utility of traditional forms, she plays with a multitude of poetic and thematic forms, pirouetting from the profane to the sacred, the mundane to the sublime, the broadly public to the deeply profound and personal with the ease of a virtuoso. Haiku is placed alongside sonnets and ghazals, interspersed with erasure, hymns, mistranslations and vers-libre to give birth to different metronomic languages and rhythms that create a new voice. Banerjee´s linguistic artfulness resides in her ability to translate all these foreign words, cultures, and geographies into a coherent language of aesthetic, philosophical, and political portent. As seen in the haiku “A Waters Sound” where the entrenchment of social conventions and power structures is metaphorically conveyed by the image of a deep, leaf-grown well from which potential young feminists are blocked from jumping out by the wire-meshed sky. The Japanese ideograms of the original poem drip silently down the face of the page, creating and holding a meditative space for the reader to ruminate upon the depth of the well. The street between Nora’s hotel and Oscar Wilde’s house is called Clare Street. Beckett’s father ran his quantity surveying business from No 6 but there is no plaque here. When their father died in 1933, Beckett’s brother took over the business while Beckett, who was idling at the time, took the attic room. Like all idlers, he made many promises; in this case, both to himself and to his mother. He promised himself that he would write and he promised his mother that he would give language lessons. But he did nothing much. It would look good on a plaque: “This is where Samuel Beckett did nothing much.”

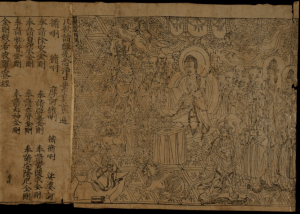

The street between Nora’s hotel and Oscar Wilde’s house is called Clare Street. Beckett’s father ran his quantity surveying business from No 6 but there is no plaque here. When their father died in 1933, Beckett’s brother took over the business while Beckett, who was idling at the time, took the attic room. Like all idlers, he made many promises; in this case, both to himself and to his mother. He promised himself that he would write and he promised his mother that he would give language lessons. But he did nothing much. It would look good on a plaque: “This is where Samuel Beckett did nothing much.” The Library Cave was bricked up some time in the 11th century, for unknown reasons: perhaps to keep the books safe from invaders; or perhaps, given the large number of worn and partial texts, the chamber was less a library than a tomb for books. Locals continued to worship at the shrines, but several of the the exterior walkways connecting the ancient cave entrances collapsed, and the sand that slowly filled many of the caves severely abraded their delicate murals.

The Library Cave was bricked up some time in the 11th century, for unknown reasons: perhaps to keep the books safe from invaders; or perhaps, given the large number of worn and partial texts, the chamber was less a library than a tomb for books. Locals continued to worship at the shrines, but several of the the exterior walkways connecting the ancient cave entrances collapsed, and the sand that slowly filled many of the caves severely abraded their delicate murals. Many black scholars—especially those who study black life, history, and culture—would recognize an uncomfortable and familiar situation that epitomizes the trials of coming through the academy: the moment when a colleague, professor, or student questions whether or not our work truly accords with the standards and conventions of our discipline, of the academy itself. We are subtly and overtly asked if our analyses are truly objective, if our methodologies are sound, and if our subject matter is accessible with wide enough appeal. We know that words like “rigor,” “breadth,” “accessibility,” and “objectivity” in traditional academic disciplines often encode institutional racism, and that the very methodologies and analytical practices we’re urged to master were never meant to accommodate the study of black life. Yet, to depart from academic orthodoxies can have real consequences: isolation, lack of support, getting passed over for opportunities and honors, poor evaluations, promotion denials, and, in some cases, exile from academia.

Many black scholars—especially those who study black life, history, and culture—would recognize an uncomfortable and familiar situation that epitomizes the trials of coming through the academy: the moment when a colleague, professor, or student questions whether or not our work truly accords with the standards and conventions of our discipline, of the academy itself. We are subtly and overtly asked if our analyses are truly objective, if our methodologies are sound, and if our subject matter is accessible with wide enough appeal. We know that words like “rigor,” “breadth,” “accessibility,” and “objectivity” in traditional academic disciplines often encode institutional racism, and that the very methodologies and analytical practices we’re urged to master were never meant to accommodate the study of black life. Yet, to depart from academic orthodoxies can have real consequences: isolation, lack of support, getting passed over for opportunities and honors, poor evaluations, promotion denials, and, in some cases, exile from academia. I remember the moment when code began to interest me. It was the tail end of 2013 and a cult was forming around a mysterious “crypto-currency” called bitcoin in the excitable tech quarters of London, New York and San Francisco. None of the editors I spoke to had heard of it – very few people had back then – but eventually one of them commissioned me to write the first British magazine piece on the subject. The story is now well known. The system’s pseudonymous creator, Satoshi Nakamoto, had appeared out of nowhere, dropped his ingenious system of near-anonymous, decentralised money into the world, then vanished, leaving only a handful of writings and 100,000 lines of code as clues to his identity. Not much to go on. Yet while reporting the piece, I was astonished to find other programmers approaching Satoshi’s code like literary critics, drawing conclusions about his likely age, background, personality and motivation from his style and approach. Even his choice of programming language – C++ – generated intrigue. Though difficult to use, it is lean, fast and predictable. Programmers choose languages the way civilians choose where to live and some experts suspected Satoshi of not being “native” to C++. By the end of my investigation I felt that I knew this shadowy character and tingled with curiosity about the coder’s art. For the very first time I began to suspect that coding really was an art, and would reward examination.

I remember the moment when code began to interest me. It was the tail end of 2013 and a cult was forming around a mysterious “crypto-currency” called bitcoin in the excitable tech quarters of London, New York and San Francisco. None of the editors I spoke to had heard of it – very few people had back then – but eventually one of them commissioned me to write the first British magazine piece on the subject. The story is now well known. The system’s pseudonymous creator, Satoshi Nakamoto, had appeared out of nowhere, dropped his ingenious system of near-anonymous, decentralised money into the world, then vanished, leaving only a handful of writings and 100,000 lines of code as clues to his identity. Not much to go on. Yet while reporting the piece, I was astonished to find other programmers approaching Satoshi’s code like literary critics, drawing conclusions about his likely age, background, personality and motivation from his style and approach. Even his choice of programming language – C++ – generated intrigue. Though difficult to use, it is lean, fast and predictable. Programmers choose languages the way civilians choose where to live and some experts suspected Satoshi of not being “native” to C++. By the end of my investigation I felt that I knew this shadowy character and tingled with curiosity about the coder’s art. For the very first time I began to suspect that coding really was an art, and would reward examination. What would convince you that aliens existed? The question came up recently at a conference on astrobiology, held at Stanford University in California. Several ideas were tossed around – unusual gases in a planet’s atmosphere, strange heat gradients on its surface. But none felt persuasive. Finally, one scientist offered the solution: a photograph. There was some laughter and a murmur of approval from the audience of researchers: yes, a photo of an alien would be convincing evidence, the holy grail of proof that we’re not alone.

What would convince you that aliens existed? The question came up recently at a conference on astrobiology, held at Stanford University in California. Several ideas were tossed around – unusual gases in a planet’s atmosphere, strange heat gradients on its surface. But none felt persuasive. Finally, one scientist offered the solution: a photograph. There was some laughter and a murmur of approval from the audience of researchers: yes, a photo of an alien would be convincing evidence, the holy grail of proof that we’re not alone. Electrons are still almost perfectly round, a new measurement shows. A more squished shape could hint at the presence of never-before-seen subatomic particles, so the result stymies the search for new physics.

Electrons are still almost perfectly round, a new measurement shows. A more squished shape could hint at the presence of never-before-seen subatomic particles, so the result stymies the search for new physics. Climate change necessarily presents a profound political challenge in the present historical era, for the simple reason that we are courting ecological disaster by not advancing a viable global climate-stabilization project.

Climate change necessarily presents a profound political challenge in the present historical era, for the simple reason that we are courting ecological disaster by not advancing a viable global climate-stabilization project.